California’s Perfect Storm

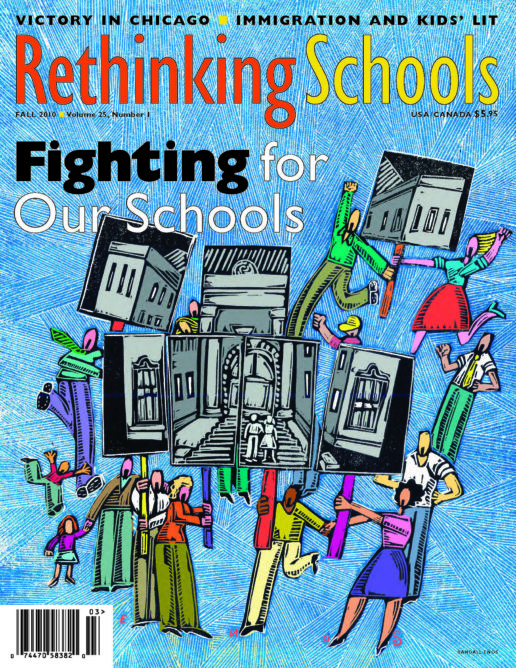

Illustrator: David Bacon

Students and teachers march in Oakland, Calif., to protest the termination of adult education programs

The United States today faces an economic crisis worse than any since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Nowhere is it sharper than in the nation’s schools. It’s no wonder that last year saw strikes, student walkouts, and uprisings in states across the country, aimed at priorities that put banks and stockbrokers ahead of children. California was no exception. In fact, other states looked on in horror simply at the size of its budget deficit—at one point more than $34 billion. The quality of the public schools plummeted as class sizes ballooned and resources disappeared in blizzards of pink slips. Fee increases drove tens of thousands from community colleges and university campuses.

But California wasn’t just a victim. Last year it saw a perfect storm of protest in virtually every part of its education system. K-12 teachers built coalitions with parents and students to fight for their jobs and their schools. Students poured out of community colleges and traveled to huge demonstrations at the capitol. Building occupations and strikes rocked the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) campuses. Together, they challenged the way the cost of the state’s economic crisis is being shifted onto education, with a particularly bitter impact on communities of color. Activists questioned everything from the structural barriers to raising new taxes to the skewed budget priorities favoring prisons over schools.

Rise and Fall of the Master Plan

When the current recession hit, California had already fallen from one of the country’s leaders in per-pupil education funding in the 1950s to 49th among the 50 states in the last decade. That fall was more than just a decline in dollars. It was the end of a commitment to its young people that started in 1960, when a wave of populist enthusiasm put liberals in control of the California Legislature and governor’s mansion. Together, they issued a Master Plan for Higher Education that promised every student access to some degree of postsecondary schooling. Community colleges were free, omnipresent, and accepted everyone. UCs had no tuition and charged only nominal “fees” for university services. Strikes led by Third World students and civil rights demonstrations opened the doors wider to people of color and youth of working-class families generally. The state’s reputation as an economic and technological powerhouse owed much to the students who passed through the system in the decades that followed.

By last year, that era wasn’t even a memory for students who have grown up in an age of shrinking expectations. Yet on paper, at least, the promise remained. In urging students and teachers on UC campuses to fight instead of giving up, noted radical sociologist Mike Davis called it an epic challenge. “Equity and justice are endangered at every level of the Master Plan for Education,” he argued. Davis called on his fellow faculty members to look out of their office windows. “Obscene wealth still sprawls across the coastal hills, but flatland inner cities and blue-collar interior valleys face the death of the California dream. Their children—let’s not beat around the bush—are being pushed out of higher education. Their future is being cut off at its knees.”

Strike! he urged them. “A strike,” he said, “by matching actions to words, is the highest form of teach-in. The 24th [the date last September for the first walkout] is the beginning of learning how to shout in unison.”

Strike!

Thousands of community college students and faculty

rallied in front of the state capitol in Sacramento,

protesting fee increases and cuts in classes and faculty.

Davis’ letter came just as the perfect storm began to build. Lightning struck first at the universities, scenes of the sharpest confrontations in California last year. California’s university system includes 10 UC and 23 CSU campuses. Organizing started even before students were back in their fall classes. “I was involved in previous campaigns against budget cuts when they were more modest,” recalls Ricardo Gomez, a UC Berkeley student leader. “We knew the state’s $34 billion budget shortfall would be used to slash money for education, and that the regents would put a big fee increase on the table. This time around we resolved to do something different, to move out of the channels of student government.”

Students and university workers created a joint strike committee that from the beginning sought to build an alliance with faculty on every campus. “The structure on each campus was open to everyone,” Gomez says. “From the first day of classes, people who’d never been involved before were turned on. . . . We wanted a mass organization to plan demonstrations. At the same time we formed committees to set up websites, make posters and flyers, and put together the marches.” In late August, the strike committee set a date for the first demonstrations—the walkout planned for Sept. 24.

One reason for what became an unprecedented level of faculty involvement was the move away from tenured positions to the widespread employment of contingent instructors, with much lower pay and little security. UC has about 19,400 faculty members, but only about 9,000 today have tenure. Highlighting the impact at UC Santa Cruz was the dismissal of Susanne Jonas and Guillermo Delgado, instructors in Latin American and Latino Studies with more than two decades of seniority each, and the end of the celebrated Community Studies program. Lecturers were the first faculty victims of the cuts on every campus.

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and UC administrators ensured the involvement of another constituency with their war on campus unions. Blue-collar UC members of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) had just won a good contract after years of fighting. They saw their gains evaporate in furloughs and layoffs. The University Professional and Technical Employees (UPTE) still didn’t have a contract, and voted to strike Sept. 24.

Stoking the anger further, a series of media exposés documented high salary increases for top UC executives. At the Sept. 15–17 regents meeting, some received increases of up to 30 percent (up to $52,000 per year) on salaries in the $200,000 to $400,000 range.

UC Santa Cruz Feminist Studies professor Bettina Aptheker called the Sept. 24 strike “the largest unified action, perhaps, in the history of the UCs. It is first and foremost in defense of public education, and then in support of shared governance, in which faculty and students, but especially faculty, are allowed to actually influence policy and decisions. Third, it is in support of all union demands for negotiations and contracts.”

Nevertheless, UC President Mark Yudof proposed a 32 percent fee increase spread over the following two years. That proposal virtually guaranteed that the November regents meeting, scheduled to vote on it, would be greeted by further walkouts. As the regents met, students occupied buildings in Los Angeles, Berkeley, Santa Cruz, and Davis. Demonstrations shook the other five campuses.

Yudof dismissed the protests in a snide commentary in the New York Times. Schwarzenegger did too. “They’re all screaming,” he said. “Everyone has to tighten their belts.” But on the campuses, the chancellors were forced to react. First they punished the students who occupied buildings. A second building occupation in Berkeley in December led to the arrests of 65 students. By then, occupations had spread into the state university system as well, over similar tuition increases and budget cuts. In both Berkeley and San Francisco, police stormed the occupied buildings rather than negotiate the exit of students, as they’d done previously.

Yet some cutbacks were reversed. Library hours that had been cut in Berkeley and Santa Cruz, for instance, were restored. In Los Angeles, protests won the chancellor’s support for more aid to undocumented students. And under the pressure of strikes and protests, UPTE finally won a contract.

Crisis Hides Restructuring Plans

Schwarzenegger and the regents were using the state’s budget crisis to move forward a much broader agenda—a shift in the way education in California is funded, what the money is used for, and who can afford higher education.

“The 32 percent fee increase not only undermines the access of students to the system, especially students of color from working families, but it’s also part of the privatization program,” explains Liz Hall, director of the UC Student Association and a UC Berkeley alumna. “Unlike the money from the state, which is restricted in the way the university can use it, the money from fees can be used any way the administration wants.” She points out that a proposal to build a UC supercomputer by Yudof’s predecessor, Robert Dynes, failed because the Legislature wouldn’t fund it. “With fee money, UC administrators can launch whatever research and pet projects they like, and grant high salaries to their cronies. The growth of those unrestricted funds is one reason we have an executive pay scandal every few years. The regents run UC like a for-profit corporation.” (In California higher ed, “fees” actually means tuition. The 1960 Master Plan outlawed tuition for higher education. A critical aspect of the disintegration of the plan has been raising “student fees,” originally meant to cover minor expenses, to amounts that can only be seen as billing for tuition.)

Shifting the funding of California’s higher education system from the state, through taxes, onto students themselves, isn’t just a program for the UC system. The state’s community college system is many times larger and the impact even more severe.

For the first time, student fee increases are now used to directly fund community colleges, which are experiencing the same trend toward tuition increases. Cesar Cota, a student at Los Angeles City College, was the first in his family to attend college. “Now it’s hard to achieve my dream,” he says, “because the state put higher fees on us, and cut services and classes.” Monica Mejia, a single mom, wants to get out of the low-wage trap. “Without community college,” she says, “I’ll end up getting paid minimum wage. I can’t afford the fee hikes. I can barely make ends meet now.”

According to Marty Hittelman, president of the California Federation of Teachers (CFT) and a former community college instructor, the system turned away more than 250,000 students in 2009–10 alone. “Where can they go?” he asks. “UC? CSU? The workforce? California has a 12.6 percent unemployment rate, one of the nation’s highest. The state universities dropped 40,000 students this year. UC fees have gone up 215 percent since 2000, and CSU fees 280 percent. Community college fees, once nonexistent, rose 30 percent just last year.

“Hundreds of thousands of students enrolled in California community colleges are unable to get the classes they needand thousands of temporary faculty are without classes to teach. So, as in the universities, the student returns for paying higher fees are increased class size and fewer available classes.”

Those cuts have an extra impact on students of color. The Los Angeles Community College District educates almost three times as many Latino students and nearly four times as many African American students as all of the UC campuses combined.

Rallies, Protests, and Sit-Ins, Oh, My

Police confronted students during the occupation of Wheeler Hall

on the UC Berkeley campus. Hundreds of students, faculty,

campus workers, and community members surrounded the building.

In protest, students, teachers, parents, union members, and community activists staged rallies at the end of November throughout California (as well as in other parts of the United States). There were large rallies in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Oakland.

At CSU Fullerton, students took control of the humanities building, saying they were “putting ourselves in direct solidarity with the ‘occupations’ that have been occurring the world over from universities to factories to foreclosed homes; from Asia to Europe to Africa to Central and South America and, now, here in the United States.”

The Fullerton students chose the humanities building to protest the corporatization scheme envisioned by the campus strategic planner, Michael Parker, who called humanities “socially irrelevant” and favored courses useful for preparing student for corporate employment. Humanities, the students said, has become “politically dangerous to the established economic order. . . . We are not surprised because we are dangerous.”

“The L.A. rally was spectacular,” enthuses Jim Miller, who teaches at San Diego City College. “The church holds a thousand, and there were hundreds more trying to get in.” He counted 565 people who came from San Diego to the Los Angeles event, including three buses of students from San Diego City College.

The protests continued into the spring. More than 8,000 students from Los Angeles and other community college districts rallied at the state capitol in Sacramento on March 22. State university campuses also sent hundreds of marchers.

‘We Can’t Fit on the Rug Anymore’

The most dramatic demonstrations were at the university level, but the crux of California’s education crisis lies in the K-12 public school system, especially in poor urban communities, and neighborhoods of immigrants and people of color. Some 22,000 pink slips were given out to public school teachers across the state in the 2009–10 academic year. “In Watsonville they’re overcrowding classes,” charges Manny Ballesteros, a youth organizer. “They’re building more prisons in California than schools, and there are more blacks and Mexicans inside those prisons. For young people like me, instead of being able to get a job, and achieving our goals, that tells you, ‘You’re not going to make it.’”

Watsonville now only has seven school nurses for 19,000 students, and has cut school psychologists and counselors, music, and art. “Sports have become pay to play,” says Jenn Laskin, a humanities and English teacher at Watsonville’s Renaissance Continuation High School. “That means students who are talented and don’t have the money lose the opportunity. That cuts off yet another pathway to college.” The state’s limit of 20 students for K-3 classes was modified in the Legislature’s recent budget deals, so next year K-2 classes will have 28 students. “We’re loading to the max. Kindergarten classes are super crowded, and one student told me, ‘We can’t even fit on the rug anymore.’

“Combined with the emphasis on test scores, it all affects children’s ability to learn,” she laments. “We have 2nd-grade students who don’t even know how to use scissors, because they’ve been taught to the test. They can bubble in letters and numbers, but they can’t cut a circle in a piece of paper.”

In Los Angeles, one of the world’s largest school districts, more than 6,300 teachers were originally set to lose their jobs before the beginning of the fall 2010 term. After unsuccessful attempts to get the Los Angeles Unified School District administration to reduce the number, teachers mounted a wave of successively more militant demonstrations. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge James Chalfant ruled that a planned one-day strike was illegal because it would “endanger student health and safety,” and threatened educators with $1,000 fines and the loss of their teaching credential if they struck. So hundreds of teachers picketed their own schools before classes started, and parents and students walked with them.

One mother, Maria Gutierrez, said the one-day strike was a good idea. “What does it matter if children lose one day of class? If we lose our teachers, they’re going to lose a lot more.” And while the district claimed poverty was forcing layoffs, it found the money to hire more than 3,000 substitute teachers to take classes in case the teachers stuck.

At the beginning of May, thousands of teachers filled the street in front of the district’s offices, and 40 were arrested for blocking it in an act of civil disobedience.

Like so many other schools districts across the country, Los Angeles has used the crisis to escalate its plans to turn public schools over to charter groups. By the end of May, a total of 20 existing schools and 27 new campuses had been put up for bid. So teachers and communities organized around that, too. After months of planning and packed meetings, many of those bids went to groups led by teachers.

Education or Incarceration?

With headlines focused on Los Angeles and the Bay Area, it’s easy to forget that California is an agricultural state. But it may be in poor agricultural communities, especially those in the San Joaquin Valley, where the state’s twisted priorities are the clearest. In the middle of a budget crisis, what will the state fund—schools or prisons?

Unemployment in California’s rural counties is often twice as high as on the coast. The economic crisis in small valley towns like Delano and McFarland was a fact of life long before California’s current budget woes. In Delano, historic home of Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers, 30 percent of the residents live below the poverty line. Desperate for employment, many were sold the idea that prisons would provide a source of jobs beyond low-wage farm labor. As a result, the area has become home to giant institutions whose budgets dwarf those of local school districts. Valley teenagers today see those prisons in their future, whether as guards or inmates, rather than college.

Every day in Delano 3,176 people go to work in the Kern Valley State Prison and North Kern State Prison. Almost as many of the town’s families now depend on prison jobs as those supported by year-round field labor. Thousands of former farmworkers now guard other Latinos and blacks—inmates just as poor, but mostly from the urban centers of Los Angeles or San Jose rather than the rural communities of the Central Valley. The two prisons have a combined annual budget of $294 million. By comparison, the town’s 2010 general fund was a tenth of that, and the budget of its public schools a twentieth.

Following the March 4 Day to Save Education, a group of teachers and home care workers began a march from Bakersfield to Sacramento to mobilize opposition to the cuts. One marcher, retired teacher Gavin Riley, describes the social cost as he saw it walking through the valley: “We’ve seen boarded-up homes everywhere. Coming into Fresno we walked through a skid row area where people were living in cardboard and wood shacks underneath a freeway, sleeping on the sidewalks. We’ve seen farms where the land is fallow and the trees have been allowed to die.

“About the only thing we’ve seen great growth in is prisons. . . . I look at that and say, what a waste, not only of land but also of people. I can’t help but think that California, a state that’s now down near the bottom in what it spends on education, is far and away the biggest spender on prisons. It doesn’t take a brain surgeon to connect the dots.”

Long-Term Strategies

The Central Valley march arrived in Sacramento on April 21, when more than 7,000 CFT and AFSCME members marched down to the capitol building to confront the Legislature and Schwarzenegger in a huge rally. They focused on one of the main demands that emerged in the sit-ins and demonstrations throughout the school year—a change in the way the state budget is adopted.

The state has a requirement that two-thirds of the Legislature approve any budget. Even more important, any tax increase takes a two-thirds vote as well. So even though Democrats have had a majority for years in both chambers, a solid Republican block can keep the state in a total economic crisis every year until Democrats agree to slash spending. Teachers’ unions, students, other labor organizations, and community groups got an initiative (Proposition 25) onto the November ballot that would remove the two-thirds requirement, so that budgets and tax increases can be adopted by simple majority.

The state also needs new sources of revenue. Assemblyman Alberto Torrico authored a bill to charge oil companies a royalty for the petroleum they pull from under California’s soil. California is the only oil-producing state that doesn’t charge the oil giants for what they take.

As the school year drew to a close, students and teachers won some partial victories. Assembly Speaker John Perez introduced the California Jobs Budget, an alternative budget proposal that would reinstate much of the education money cut over the last year. He also promised to roll back the UC and CSU student fee increases by 50 percent. Meanwhile, Gov. Schwarzenegger’s revised budget reinstated Cal Grants program funding, although it cut money for the poorest recipients of state aid at the same time. (By press time in September, the state legislature had still not passed a budget for the current fiscal year.)

“I don’t feel good that we saved Cal Grants at the expense of single mothers and children,” says Claudia Magaña, a student leader at UC Santa Cruz. “It’s great to know that students had some power this year, but not that we won at the expense of the neediest people. We have to look at who has power in this system and how to get it.”

Coming out of the year’s actions, Magaña voices the conclusion of many student leaders and teachers—that education activists need a strategy for the long haul. “We need [a strategy] to win long-term reinvestment in the system,” says Liz Hall. “We need a power analysis that will help us to build our movement. Preserving the public nature of education will take large-scale changes. This was a year of crisis for us, spurred by fee increases and furloughs. Now our bigger problem is how to get mobilization and commitment for much larger goals. To begin with, we have to get our students to turn out in November.”

But giving more power to Democrats, and a better system for arriving at a budget deal, won’t automatically reverse the state’s priorities. Democrats vote for prisons, too.

K-12 teachers, students, home care workers, and

community activists on a 260-mile, 48-day march

from Bakersfield to Sacramento to protest cuts to

education and social services.

Jim Miller says the demonstrations, and especially the Central Valley march, show that “we can fight for an economy and a government that work for everybody. We’re not saying save education by throwing old people out of their home care, by getting rid of health care for poor kids, by closing down state parks, or privatizing prisons. This is about the future of the state of California.”

Without unity, he says, “we’ll see a scarcity model, where people say take someone else’s piece of the pie, not mine. That’s a race to the bottom.”

Perhaps fighting itself was the year’s biggest achievement. Across California, new alliances of teachers, students, state workers, communities of color, and working-class communities in general took on the challenge. Their strategic ideas ranged from student strikes and walkouts to alliances between communities and unions, a sophisticated agenda of legislative solutions, and mass mobilizations in rallies and marches. Although there was a broad variety of activity, a common thread highlighted the special impact education cuts have on communities of color and working-class families. A social movement is growing across the country to defend public education. California’s perfect storm was at its leading edge, and contributed a new repertoire of strategy and tactics for building it.

| San Diego Students Protest Racist Attacks At UC San Diego, the storm took on a particular character due to a series of racist events on campus. The string of incidents began in February, Black History Month, when white fraternity students organized a “ghetto-themed” party called a “Compton Cookout.” It was followed by a campus television show that mocked Black History Month. A few days later, a student hung a noose in the UCSD school library. Anti-hate rallies were organized at other campuses in response, and students sat in at Yudof’s Sacramento office. As students geared up for March 4, a KKK-style hood was found with a hand-drawn circle and cross on the statue of Dr. Seuss outside the UCSD library. At a rally organized at UCLA in protest, student Corey Matthews asked: “What kind of campus promotes an environment that allows people to think it’s acceptable to target people for their ethnicity, gender, or sexuality? It’s something about the tone of the environment that allows this.” A month later, UCSD administrators took action against Ricardo Dominguez, an art professor who developed a project to help migrants crossing the desert between Mexico and the United States use their cell phones to orient themselves, and find help in an emergency. Hundreds of migrants die in the U.S. desert each year because they cannot locate water or find shelter from the heat. Conservative Republican Congressman Brian Bilbray objected to university administrators, who placed Dominguez’s tenure under review. According to Graceland West, a San Diego student leader: “We need more resources for immigrants and people of color on this campus. Instead, a professor with a long history of support for us is being punished for taking a pro-immigrant position. When we have cuts to enrollment and student services, and a lack of financial aid, students of color are the hardest hit. Many now see UCSD as a racist campus. At the same time, higher fees hit high school students thinking about coming here. All this basically deters students of color from applying.” —D.B. |