Preview of Article:

Border Tradition on the Line

Community Rallies Behind Mexican Students

The stage was set for the disenrollments when the Deming School Board unanimously adopted an enrollment policy in June 1996 that banned the new enrollment of “out of district” children, referring somewhat euphemistically to the children who come from Las Palomas, Mexico. For children enrolled before the 1995-96 school year, enrollment would be offered only on a “space available” basis.

The new policy was in part the result of increasing polarization in the U.S. towns of Deming and Columbus over the issue of providing education to children who live in Mexico. Many newcomers to the region, primarily retirees from faraway states such as Wisconsin and New York, have openly challenged the school district’s previously unquestioned policy of open enrollment. Furthermore, a few longtime Anglo residents still carry a grudge from a 1916 attack on the village of Columbus, allegedly led by Mexican revolutionary Francisco (Pancho) Villa. Eighteen Columbus residents were killed in the surprise raid, now legendary as the last invasion of U.S. soil by a foreign army.

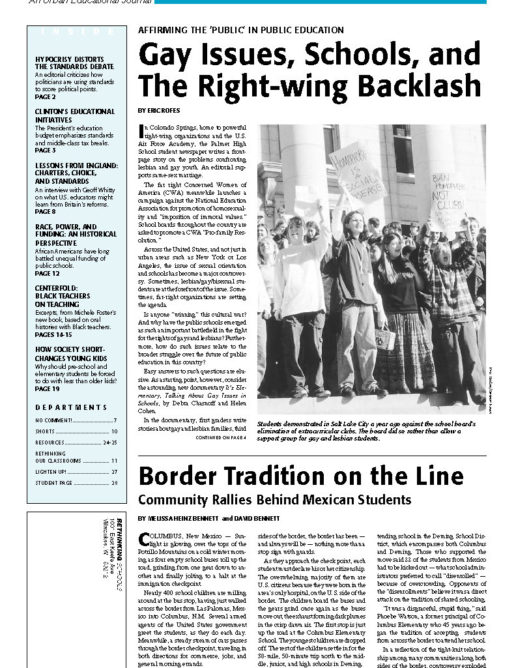

Opponents of “disenrollment” argue that the Mexican children are conveniently being used as pawns in a larger problem that the district’s enrollment is growing and taxpayers, especially retirees, are reluctant to put the resources necessary into the public school system. They note that of the 5,400 students in the district, only 380, or 7%, come from Las Palomas, Mexico.

The arrangement of shared schooling reflects a historic relationship between New Mexico and Mexico which sets it apart from other U.S. border states.

Many of the oldest New Mexican families trace their bloodlines, cultural identity, and ownership of land to the Spanish conquistadors and settlers who first came to the region in 1539. What is now New Mexico, for instance, was colonized by the Europeans nearly a quarter century before the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth Rock. In the 1600s, a vital trade link between Mexico City and Santa Fe was established; for hundreds of years, residents of Mexico thought of the Rio Bravo (as the Rio Grande is known in Mexico) not as a boundary or a border, but a simple river crossing. The land that is now New Mexico was made a Mexican province in 1821 and was seized by the United States during the War with Mexico in 1848. New Mexico did not become a state until 1912. The state constitution explicitly guaranteed educational equality to all Spanish-speaking students.</p