Mirrors and Windows: Conversations with Jacqueline Woodson

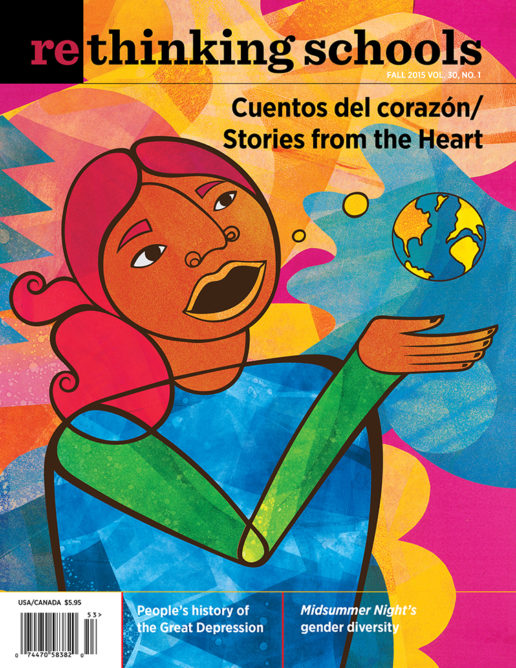

Illustrator: David Flores

Photo credit: David Flores

It is March 2015. America is reeling from the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, John Crawford, and Ezell Ford. As the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter is trending, images of unarmed Black women killed by white shooters begin streaming on Twitter feeds: Aiyana Jones, Renisha McBride, Shereese Francis, Rekia Boyd. Gay marriage is debated; violence against transgendered youth persists.

There was a lot to talk about.

I was honored to be in conversation with Jacqueline Woodson at the Schomburg Center in Harlem to celebrate her award-winning new novel, Brown Girl Dreaming, and mine, This Side of Home.

There was no way we could talk only about our lives as writers. Talking about why we write meant talking about our history as Black women—Black women who have little ones we worry about because they, too, might one day fit the description, be at the right place at the wrong time. I knew Jacqueline wouldn’t want to ignore the backdrop of our conversation. Her stories are filled with characters who don’t fit into neat, predictable boxes about what it means to be a girl, or Black, or gay, or white, or a teen. There is no shying away from difficult, painful topics. Light and dark are always present, side by side. Her books mirror reality.

Jacqueline’s love for writing started when she was a child: “Sometimes, when I’m sitting at my desk for long hours and nothing’s coming to me, I remember my 5th-grade teacher, the way her eyes lit up when she said, ‘This is really good.’ The way, I—the skinny girl in the back of the classroom who was always getting into trouble for talking or missed homework assignments—sat up a little straighter, folded my hands on the desk, smiled, and began to believe in me.”

That is who Jacqueline is writing for. The child in the back of the classroom, the one buried in a book, creating paragraphs in a hidden journal. She is writing mirror books for young Black children who need to see themselves in the pages of a story. She is writing window books for readers to strengthen the muscle of empathy and look into someone else’s world.

A few weeks after our Schomburg conversation, and after Jacqueline had been named Young People’s Poet Laureate by the Poetry Foundation, she answered questions for Rethinking Schools readers:

Renée Watson: Many of your books deal with the intersection of race, sexism, gender, and sexuality. Why do you weave these together in your stories?

Jacqueline Woodson: I think it’s important to respect the genre of realistic fiction by keeping it real. I also am concerned with making sure the stories of people who have been historically missing from our body of literature are on the page. I try to mirror their experiences in the real world. My hope is that my work reflects a broad range of identities and experiences.

RW: Your books are so rich in terms of character development, dialogue, and taking on social justice issues—how do you balance all of these elements without being dogmatic?

JW: I have a deep respect for my audience. I know that young people read to experience a good story, another world. They read for the same reasons that I read. And I never write to teach—I write to learn. I write because I have questions, not answers.

For example, If You Come Softly, which I wrote long ago, is a retelling of Romeo and Juliet. I remember there were (and sadly, it hasn’t changed) so many cases of police brutality against Black men going on. I thought: If people could see my character as human and truly love him, what would that mean? What would that look like? Who would he be? Would that make people want to change the world?

RW: One of my favorite moments in Brown Girl Dreaming is when your big sister guides your hand with hers and teaches you how to write your name. Throughout the book we see a strong sisterhood between women of the older generation and the younger. How will mentoring younger generations be a part of your role as the Young People’s Poet Laureate?

JW: I’ve had mentors without knowing that’s what they were—teachers, parents, neighbors, friends, books, authors, newspapers—the list goes on. Every piece of something or someone who inspired me became a mentor. And this is what I hope to bring to my role: I want young people to see poetry everywhere, to understand that we can live lives as poets just by showing up, being present, bearing witness to the world we live in. I want young people to understand they have stories to tell and poems to write.

RW: Brown Girl Dreaming opens with a poem about the day you were born:

. . . I am born as the South explodes

too many people too many years

enslaved, then emancipated

but not free, the people

who look like me

keep fighting

and marching

and getting killed

so that today—

February 12, 1963

and every day from this moment on,

brown children like me can grow up

free. Can grow up

learning and voting and walking and riding

wherever we want . . .

This could very well be about the times we are currently living in. How can parents and educators encourage young children—especially brown children—to hold onto their dreams and self-worth as movements like Black Lives Matter remain necessary?

JW: Love them up. Let them know they’re loved. Let them know that you’re behind them. Teach them how to walk safely through the world. Teach them how powerful their brown bodies are. Read Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Impart the knowledge he’s passing on.

RW: Many educators shy away from discussing race, sexism, gender, and sexuality. How do you hope teachers use your work in the classroom?

JW: First and foremost, I think we should be careful not to bring our own fears and discomforts to the classroom. My books aren’t about race, sexism, gender, etc.—they’re about people in the world and they’re stories that, hopefully, will keep young people entertained as they reflect on a greater good. So the first thing to do is introduce them this way—not via the vehicle of our own prejudices.

I’ve heard people say From the Notebooks of Melanin Sun is a book about a mom who is coming out. And to the adult, maybe that’s the first story they see because they’re looking at it through their own lens. But to the young person, it’s the story of a boy trying to figure out who he is in a changing world and he’s embarrassed by his mom—what young person doesn’t know that story? So, my hope is that teachers are presenting my books through the young person’s lens.

RW: Often, when students learn about Langston Hughes and Lorraine Hansberry, their sexual orientation is not included. Many people don’t realize until they are adults that these writers were gay. Do you think it’s important for young readers to know the sexual orientation of the author they are reading?

JW: I think it’s tricky because it comes back to the lens: How is this writer being presented? How is their sexuality being introduced? Is this the first time sexuality is being discussed in the classroom? We don’t want students to fixate on sexuality and not see the beauty of the work. It’s complicated, and I’d rather a teacher who is uncomfortable with discussing sexuality just talk about the work. Once the student falls in love with the writer, they will follow them anywhere—and eventually want to know more about them.

RW: Do you call yourself an activist? Do you ever fear that being outspoken about social justice issues will affect your career in a negative way? What advice can you give teachers who struggle with that dilemma?

JW: I am an activist and, as an activist, I can’t walk through the world afraid. I think my fearlessness has allowed me to do some of my best writing. My biggest fear would be to be dishonest to myself, to live a half-life, to not tell the stories I was put here to tell.