Big Reactions to Small Steps

One Teacher’s Story About Using Inclusive Children’s Literature

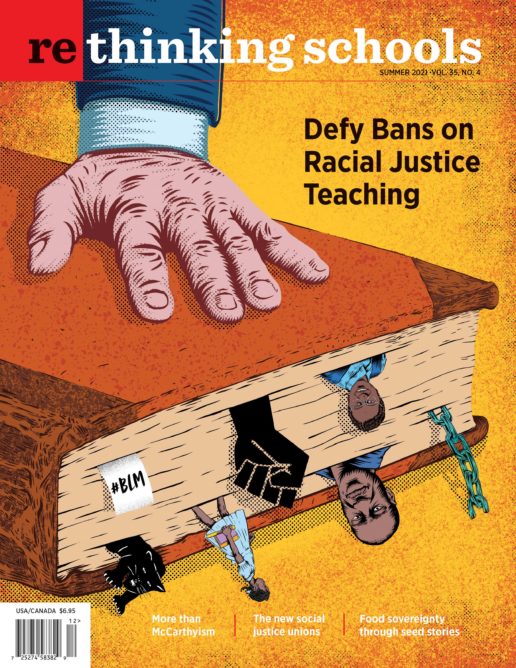

Illustrator: Ebin Lee

“Please remember,” a human resources representative said from behind the podium, “this is a conservative county.”

After teaching for 10 years, I had relocated with my family to a rural community in central Virginia. The orientation was in a high school auditorium, and here I was, listening to human resources personnel tell a story about a teacher who lost her job because a parent insisted she didn’t fit within the conservatism of the local community.

After the orientation, we teachers went back to our respective public schools. At mine, the introduction to the school year included a Baptist minister urging us to bow our heads and hold hands as he prayed for a successful school year.

To be clear, I taught alongside many inspiring educators in this community. At the same time, signs of social conservatism are embedded in all the county’s institutions, and conformity to a Christian, heteronormative value system is a clear and socially enforced expectation. Local representatives are quick to protect their constituents’ rights to discriminate against anyone who does not conform. They ignore the rights of those who are being discriminated against. Because this discrimination has become so normalized, many see upholding this status quo as “remaining neutral.” Although this is, of course, a false definition of neutrality, it enables many to ignore issues of discrimination — a course of action that is easier anyhow — by promising that their supposed neutrality is a sign of professionalism rather than a moral shortcoming. It makes it easier to justify injustice. I have seen this mindset have significant repercussions in issues of sexism, racism, and homophobia.

If you had driven down the highway that cuts through this county in 2019, you would have seen signs mocking the identities of transgender students in our schools. In local Facebook groups, parents posted denigrating comments about trans children and their families. At school board meetings, community members made offensive statements about LGBTQIA+ students, pitting trans students’ rights against those of “natural born females.”

When a group of teachers drafted a non-discrimination policy in response, the school board refused to include language that referred to “accepting and acknowledging students’ individuality based on sexual orientation or gender identity.” Refusing to name the existence of the oppressed group was characterized as “neutrality,” and acknowledgement of oppressed populations was deemed “controversial.” The message is clear: Pretend discrimination does not exist, and you will be rewarded. Acknowledge the existence of oppressed or non-conforming populations, and your professionalism will be attacked.

So when my 2nd-grade student asked, “What does gay mean?” my first thought was that my administration would expect me to not answer the question and refer the child to their parents. I also knew that this was why it was important to address it, particularly when the student revealed that another student had been calling children gay at recess. Avoiding the question would send a strong message to my students. So I decided to address it.

A Small Step

“Being gay is part of someone’s identity. If someone is gay, that means they may fall in love with someone who is the same gender. Love is what makes a family, right? Well, families are made up in many ways,” I said, “and many have two mommies or two daddies. Families can include a man and woman, two women, or two men who love each other and have decided to share their lives together. All families are different from one another, and every family deserves respect.”

It was, I admit, a less-than-progressive entrance into the conversation than I would have used in other circumstances. This explanation did nothing to challenge the binary and stayed within the context of families. I chose this entrance point because it would ground the children in familiar territory. Since these students had learned about heterosexual nuclear families from infancy, I thought this might be a helpful starting point. Students could begin to broaden their awareness by synthesizing old information with new.

Many children were surprised that same-sex couples existed, but respect for all people and families seemed to resonate with them. One student mentioned that he knew a family with same-sex parents. Another mentioned that his mother’s friend was gay, and another student raised her hand and said, “It’s not OK to make fun of other people, especially when you’re making fun of their identity. Then you’re making fun of that person plus a lot of people you don’t even know.”

I thought it was the perfect time to take out Rob Sanders’ Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag.

This beautifully illustrated book begins with Milk’s famous words: “You have to give them hope. Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow. . . .” It describes how San Francisco activist Harvey Milk became famous for supporting gay rights and how he worked with Gilbert Baker to create the rainbow flag, a symbol “to make people feel they’re part of a community. . . . Something extraordinary.”

Pride is rated for children 5 through 8 years old. It is a Junior Library Guild selection, recommended for all ages by School Library Journal. Our town’s public library owns the book, as did one of the schools in our district. The book has some shortcomings: It is not a fully comprehensive representation of many LGBTQIA+ experiences, does not offer connections to the broader movement, and lacks racial diversity. Yet it does reflect values of inclusivity portrayed in many of the texts taught in our state-mandated curriculum, which included figures such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, and Helen Keller. This was not lost on my students.

“I’m making a connection!” one of the children called out. “Harvey has a dream like Martin Luther King — about being treated like everyone else! And he’s making speeches about it!”

“Yeah,” said another. “And people are marching about it, too!”

A quiet voice joined in: “Someone shot him, too. It doesn’t make sense to hurt someone just because you’re not exactly the same.”

Many children mumbled “yeah” and nodded heads in agreement.

And then a parent complained.

Homophobia in Schools

One mother was upset that her child knew what the word “gay” meant. She was angry that I compared Milk to other civil rights leaders. She contacted the principal, superintendent, and media. She was on the news declaring that I had denied her her rights as a Christian. Our principal told her I had “made poor judgment” and apologized. Other parents in our class who had contacted the school supported the book and the conversation; however, community members beyond our classroom saw the media coverage and many were outraged.

The principal held a meeting that morning to reveal a policy: Teachers must have “sensitive, controversial material” vetted by the school district before presenting it to students. If it were deemed appropriate, we would send a letter home ahead of time allowing parents to opt out of the lesson. Later that day, the administration sent a letter home with my students saying I had not followed that protocol.

That same year, administrators told some of our high school teachers to remove Safe Space stickers from their doors because they might alienate straight students.

Sadly, I know that mine is far from the only school in the country that functions this way.

There is a startling pattern of schools nationwide ignoring the abuse of LGBTQIA+ students. In 2017, GLSEN’s National School Climate Survey found that 98.5 percent of LGBTQIA+ students heard the word “gay” used negatively in schools, and 70 percent heard it frequently. Almost all LGBTQIA+ students (87 percent) reported harassment or assault based on personal characteristics. But only 55 percent of these students reported these incidents to school staff because “they doubted that effective intervention would occur or feared the situation could become worse if reported.” More than 60 percent of the students who did report an incident said school staff did nothing or told the student to ignore it.

I realized this was one small opportunity to interrupt this oppression.

Initiating Discussions

First, I applied pressure from within the building by initiating discussions about LGBTQIA+ rights with administrators and colleagues. In conversations with my principal, I pointed out, “Statistically, we do serve LGBTQIA+ families and children.” Indeed, a 2020 Gallup Poll found that 15.9 percent of Generation Z Americans self-identified as LGBTQ. A growing awareness and inclusivity within communities means that number is growing with each generation as people who identify as LGBTQIA+ feel free to be themselves. I told our principal that although our students were young, there were certainly children who were struggling with peer taunting, weaponized by gender stereotypes. Students were trying to make sense of their identity and gender expression in the confines of a community that provided no models for the many healthy experiences and lives beyond cisgender, heterosexual, Christian conservatism.

A few days later, the principal called me into a meeting with the assistant principal.

“We want you to know that you have our support,” the principal said.

“You are on record saying that I made poor judgment. That doesn’t feel like support,” I responded.

“I apologized to the mother,” she admitted, avoiding eye contact.

“Our point is, we don’t want you to feel alone,” the assistant principal said. Then she said, “No one is banning any books here. We just need to let parents have the opportunity to opt out of these discussions.”

“This was in response to a student calling kids gay,” I responded. “We don’t give families the opportunity to opt out of anti-bullying lessons, so why would we in this case?”

“Well, maybe we should,” the assistant principal replied.

Dumbfounded, I did not respond.

My principal went on to talk of how “many people feel that traditional family values are under attack.”

“But they’re not,” I replied. “Families being presented with other ways of doing things is not an attack.”

“Well, that’s your opinion,” she replied.

The next day, the librarian told me, “Think of it this way: It’s just like how parents should be able to choose when their kids learn about Santa Claus and the Easter bunny.”

“You understand that your argument relies on comparing the LGBTQIA+ community to fictional characters, right?” I asked.

She ended the conversation.

I did have colleagues come to me and show support, even if in secret. Many teachers articulated support for the LGBTQIA+ community and for more inclusive literature and curriculum. One told me she had made that clear to our principal. People placed small gifts, letters, and cards at my classroom door. A former student’s family brought me a pie. These gestures left me feeling both supported and relieved but also embarrassed. Creating a space where all students are represented should be a basic expectation. No gifts required.

Pressure from Our Community and Beyond

Many of my students’ parents called the principal, superintendent, and school board members to voice their support. I contacted a local progressive group, who in turn, rallied parents to attend school board meetings and make public statements.

“This book is not about sex. . . . It is a book about identity, history, and human rights,” one parent said at a meeting.

Another stated, “We may not censor our children’s education based on someone’s religious beliefs.”

“I would hope,” said one mother, “that my child’s family is not considered by your school to be too controversial to acknowledge.”

I also contacted national organizations. The Southern Poverty Law Center’s Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance) division sent materials to our school board and administration. The National Coalition Against Censorship and the National Council of Teachers of English sent a letter pointing out that “books that honor LGBTQ histories and narratives are disproportionately censored in schools, chilling LGBTQ voices in the community . . . [whose] youth face serious threats to their mental and physical health.” In their letter, they advocated that we adopt Pride as part of our curriculum, citing our school district’s Code of Conduct, which recognizes “the importance of the dignity and worth of each individual.”

Copies of letters were sent to the superintendent, administrators, and school board members. The local progressive group found parents to read these letters at school board meetings. Local advocacy groups such as Equality Virginia and Side by Side also attended meetings and made statements citing statistics of LGBTQ student attendance, performance, and graduation rates when students were part of inclusive school communities compared to when they were not.

The Response

The school board meetings concluded with the superintendent diplomatically recognizing that the board had heard opinions on “both sides” of the issue and thanked everyone for coming.

I have since learned that the one school district copy of Pride disappeared from the school library. The district claims that it never owned it in the first place.

However, because of community activism, the issue is not going away. Side by Side offered an LGBTQIA+ student support class for our community in the fall of 2019, and an LGBTQIA+ equity session was offered for teachers as part of our district’s summer professional development. The district created an equity team with teachers from a variety of schools working to develop a non-discrimination policy. As mentioned, the administration’s approach was to put a blanket policy in place without naming any particular goals regarding specific populations within our community.

In hindsight, I’ve thought about how educational policies that don’t address issues of equity limit students’ access to an education that liberates and empowers them. “Controversial materials” policies ensure that homophobic, sexist, and racist ideas dictate how we teach students and future leaders.

But we can push back on policies, prejudice, and “remaining neutral.” By engaging in one-on-one conversations in our schools and partnering with local and national social justice organizations, we can work toward a curriculum that honors children’s natural curiosity and the healthy expression of diversity within our communities. Engaging students in conversation through inclusive literature is a small, but important step.