Beyond Just a Cells Unit

What My Science Students Learned from the Story of Henrietta Lacks

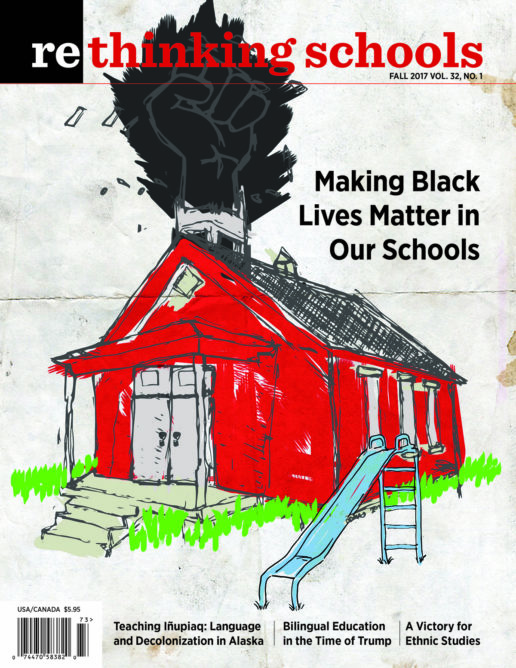

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

Every year when I distribute The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot to my biotechnology class, I am greeted with “Turner, this isn’t English class!” And every year I tell my students, “I promise you: This book is going to change the way you think about science. Give it a chance.”

I make this promise to my students because I know the beginning of the story will pique their interest. Skloot brilliantly describes the beginnings of both Henrietta Lacks, the woman, and HeLa, the first immortal cell line, in a way that gains the interest of a wide swath of students. Henrietta’s daughter, Deborah, is quoted on the first page: “When I go to the doctor for checkups I always say my mother was HeLa. They get all excited, tell me stuff like how her cells helped make my blood pressure medicines and anti-depression pills . . . but they don’t never explain more than just sayin, Yeah, your mother was on the moon, she been in nuclear bombs, and made that polio vaccine. . . . But I always thought it was strange, if our mother’s cells done so much for medicine, how come her family can’t afford to see no doctors? I used to get so mad. . . . But I don’t got it in me no more to fight. I just want to know who my mother was.”

Students who take my class out of a pure interest in science get what they came for in the descriptions of lab science and discoveries about cells and cancer. And, students who take my class because a family member or teacher said they should be in the biotech program get drawn in by family stories, the tales of Henrietta being shuffled around amongst family members and her children growing up without a mother — all with the ease of reading a well-told, captivating story. And students who have not seen themselves in science history hear the voices and stories of Black women front and center — sometimes for the first time — from the very beginning of this book.

When students come back the second day after getting the book, they are excited, saying: “OK, this book is alright” and “I didn’t think I’d like it this much” and “She’s Black?” and “Wait, her cells are still alive?”

Rebecca Skloot was a high school student at an alternative school in Portland, Oregon, when she first heard a story about a Black woman whose cells have immeasurably changed our understanding of the very basics of biology. Skloot was taking a community college course when an instructor mentioned Henrietta Lacks during a lecture on cell division. He told the class that Henrietta’s cells had led to great discoveries, that her cells continued to live decades after her death in labs around the world, that her cells were the first to do this, to be immortal, and he told the class she was Black. At that point, this was about all that the scientific community really knew of Henrietta Lacks, the woman whose cancer cells, which grow and divide very quickly and remain a laboratory staple today, would be used to add volumes to our understanding of cells, genetics, and a host of other fundamental areas of science. Skloot remained curious about Ms. Lacks as a person, and went on to write a book that told the story of Henrietta, her family, and how the cells came into the hands of doctors, scientists, and Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1951.

Skloot’s book on Henrietta Lacks is a fascinating account of her previously hidden story. The writing expertly weaves the journey of the Lacks family’s tireless work to uncover the story of Henrietta’s cells with both scientific and African American history. The basic narrative is that Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Baltimore, sought care for cervical cancer in a segregated hospital, and in the process of doing so, white doctors and scientists took her cancer cells with dubious consent, believing that the patients of the “colored ward” were essentially trading being research subjects for health care. The impacts of this incident specifically, and inequalities in health care more generally, affected Henrietta’s children and grandchildren immensely. The importance of her cells to the scientific community cannot be overstated, and yet the Lacks family never saw any of the money generated from the innumerable discoveries from the cells. Henrietta’s descendants struggled with poverty, including battles with getting proper health care, and were left in the dark — the consent forms then were rudimentary, at best — about what doctors and scientists both took and found. One can infer that had Henrietta been white with more resources, either her cells would never have been taken in the first place or her family would have received recognition for their mother’s profound contribution to science.

The book combines the science behind why her cells are so important with personal narrative in a unique way. As a science teacher in the only majority African American high school in Oregon, I thought my students would find the story an engaging way to learn about cells (particularly cell growth and cancer), how research protocols have evolved over the last 100 years, and about the intersections of institutionalized racism and biomedical history. We typically spend about six weeks on the book, and the richness of the story, both in science content and my students’ ability to relate to the Lacks family, make this relatively long unit worthwhile.

Reading the Book to Teach the Book

Before reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I had never considered using a book that more resembles a novel than an academic science text in my classes. I initially thought we could maybe read a section of the book before doing some more serious work on how cells grow. The story would be a small feature of a cell unit, not cells being a section of a book unit. But, after reading the book, I couldn’t pick out just one section or one passage and contain the powerful story to a mere sidenote to a cell unit.

As a science teacher, I had no idea how to teach books — this wasn’t ever addressed in our pedagogy courses, nor did I have examples from other science teachers of how to do this. I wanted the process to be familiar to my students, so I worked with English teachers at my school to learn how they taught books. I learned how to do dialogue journals and teach students to take notes with a final paper in mind. When I read the book, I thought about what I would do if I were asked to write a paper on the story, and I picked several themes: Medical Apartheid (a term coined by Harriet Washington to describe racial inequity in health care), Informed Consent, Lab Science, and Scientific Discoveries. Then I re-read the book, this time keeping a dialogue journal with quotes on one side and my comments on the other. I divided my notebook into five sections with the themes listed above and a fifth one titled “Family.” I created discussion questions for each chapter and found supplemental readings about cell culturing, cancer growth, and rights to one’s own tissues and genetic codes (in subsequent years, the amount of supplemental articles on Henrietta exploded and this became easier). I also kept an eye out for when I could do labs alongside the reading to bring to life what the scientists did in the book.

As the unit developed over the years, more research has come out about Henrietta’s cells, including bioethical violations such as publishing the genetic code of HeLa (which was a violation of her family’s rights to their own genetic codes). Continuing to monitor the New York Times science section (where Rebecca Skloot has published updates to the initial narrative, including “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, the Sequel” in 2013) helps tremendously with making sure the supplemental readings I give my students are current.

Other supplemental materials stemmed from students wanting to know more about the examples of medical apartheid discussed in the book. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, a long-term study conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service on untreated syphilis in Black men that went on decades after the cure was found, is referenced several times throughout the book, but the most chilling descriptions of how African American people were treated comes in a chapter called “Night Doctors.” This chapter outlines much of why African American people have reasons to distrust the medical establishment and includes stories of enslaved people being used for “gruesome research,” Black people being kidnapped off the streets to be used in medical studies and as cadavers, and more recent studies looking for genes that could predict criminal behavior by studying Black families. Dr. Harriet Washington’s book Medical Apartheid is an excellent resource for students wishing to learn more, as is the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s website on the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

Cell Culture

Cell culturing is central to the beginning of the book. Scientists tried for decades to grow human cells outside of the human body before finding Henrietta’s immortal cells. While we obviously can’t grow human cells in the classroom, the process of even much more basic cell culturing was new to my students. I designed a lab on yeast culturing, a eukaryotic cell often used in genetics experiments, that we did as we read about the first ventures of human cell culture. The lab was a simple exploration into how to maximize growth and minimize contamination. And the supplies to do such labs are actually relatively inexpensive. I used baker’s yeast from the grocery store for my cell source, and ordered basic petri dishes and a yeast-peptone-dextrose (YPD) media. Students made a media with 25g of YPD and 10-15g of agar per liter of distilled water and poured this into the petri dishes, which then sat overnight to solidify. We mixed a small amount of the yeast with table sugar in warm water (just as you’d do when baking bread) and then poured that mixture onto the plates. We grew the yeast at both room temperature (25 C) and in an incubator at 37 C (human body temperature). When growth didn’t occur or contamination from bacteria took over the yeast growth, I tell my students, “These issues are the same as what the scientists in the book faced. This is real science.” We work to problem-solve the issues and compare growth at different temperatures. We also discuss how contamination occurs and why sterile environments are so important. I ask, “Why do you think contamination can occur if we keep the lid open too long?” or “How come yeast grows best at body temperature instead of room temperature?”

Teaching About Cancer

As we continued to read the book, I found that students needed to know more about cancer and what happens when the mechanisms of the cell cycle go awry. My students had a lot of questions: “Why can’t the scientists use any of her cells? Why only the cancer ones?” I answer that “Only the cancer ones have the mutation that causes the cells to divide uncontrollably.” Another student, Ny’osha, wanted to know “If Deborah (her daughter) gets cancer, will those cells be immortal too?” “Not necessarily,” I responded. “This could depend on if her cancer was purely genetic or due to viruses.” And Marti, somewhat indignantly, wanted to know “If her husband hadn’t been messing around, would Henrietta have even gotten that cancer?” “Probably not!” I answered. “Let’s talk about oncoviruses!”

The first year I taught this unit I did a review on mitosis and then directed my students to the National Institutes of Health’s websites on cancer. Each student did a worksheet on mitosis and wrote a generalized summary of how cancer works. Henrietta’s cancer was more robust than most cancers, the vast majority of which would not survive outside the human body. The disruptions to the cell cycle that her cancer caused are representative of many cancers and it’s important for the students to understand how cancer cells generally differ from healthy cells. For the last few years of teaching this unit, I also use an article titled “UW researchers report on genome of aggressive cervical cancer that killed Henrietta Lacks” and show a PowerPoint on HPV and cervical cancer by Lydia Breen and Rebecca Veilleux from an MIT/HHMI Summer Teacher Institute.

My students write short responses to questions such as: What was the “perfect storm” that went wrong in Henrietta’s cervical cells? What is a haplotype and what unique information does it give scientists? Why was publishing Henrietta’s genome problematic for her family? Why must participants give materials (like cells) for research to occur? Explain the relationship between telomeres and cancer cells’ immortality.

Bioethical Issues

The cell culturing and cancer portions take up about the first four of the six-week unit. I teach these as short units that cover basic reviews of cell function and division. As well as diving deeper into those subjects, we set aside time to have discussions around the bioethical questions raised in the book. Discussions take place as a whole class and in small reading groups that I establish when we first start the book. The reading groups meet weekly and discuss a set of questions (some of which are from Random House’s Teacher Guide) for each section. I write out the questions and give them to the students before they read the corresponding chapter. In these groups, the students are able to relate the science they learned in class to the Lacks family story. The book details Henrietta’s life, from being raised, along with her cousins, by her grandfather after losing her mother at age 4, to having five children with one of these cousins. Her life started on a tobacco farm in rural Virginia and ended in Baltimore.

While Henrietta is most famous for her immortal cells, my students relate to her on a human level. One student, Asianique Savage, opened her final essay with: “A woman with brown skin as smooth as the back of a chocolate bar, thick long hair as strong as rope, who made sure her nails were always done, painted with bright red nail polish, was brought into the world August 1, 1920.” This sentence is not what one typically thinks of as “science writing,” and yet it captures how my students see Henrietta.

Deborah Lacks, Henrietta’s youngest daughter, is a central character in the book. Her anger at losing her mother and not fully understanding the science behind why her mom is so famous creates some tension throughout the book. In response to the question “What does Deborah mean when she says (p. 235), ‘I do want to go see them cells, but I’m not ready yet’?” Keisha said that she sees “why Deborah is always so mad and she’s stressed all the time. She doesn’t have her mom, the doctors disrespect her and her family, and they’re poor while all those people make money off of drug patents. She didn’t even really know what a cell was, let alone why her mother’s were still alive. It’s complicated for her.”

Through the story of the Lacks family, my students are also able to explore the deeper questions of how race intersects with medical history as a whole. Questions like: “Describe HL’s medical history. Why do you think she cancelled appointments, stopped treatments, and refused tests?” “How were HL’s tissues obtained? Did she consent? Does it matter?” and “Why did the doctors in the ’50s use patients from public wards for research?” were designed to get students to think about how Henrietta, as a Black woman, could have been fearful of going to the hospital. Henrietta’s distrust in medical institutions is still seen today in Black culture as described by Vann R. Newkirk II in a 2016 article in The Atlantic titled “A Generation of Bad Blood”:

Research has long suggested that the ill effects of the Tuskegee Study extend beyond those men and their families to the greater whole of Black culture. Black patients consistently express less trust in their physicians and the medical system than white patients, are more likely to believe medical conspiracies, and are much less likely to have common, positive experiences in health-care settings. These have all been connected to misgivings among Black patients about Tuskegee and America’s long history of real medical exploitation of Black people.

My students understand this at a personal level: “They would never take the cells from a white woman like that,” claims Ty. “But look at what was accomplished with them. They shoulda asked her and gotten her permission though,” adds Aliyah. Near the end of the book, I ask my students, “Do the scientists owe the Lacks family anything? Does the lack of consent impact your thoughts on reparations to the family?” Many of my students wrestled with this question as part of their final paper.

The Culminating Paper

Once we are about two-thirds through the book, I have the students start to work on their final papers. The students’ composition books were divided into the same categories that are choices for their final papers: Medical Apartheid, Informed Consent, Lab Science, Scientific Discoveries, and a fifth category, Family, as this theme is so critical to the story that my students could not write any paper without including the story of the Lacks family. As they read the book they jotted down their notes in these five sections, and for most students, one of the categories eventually emerged as the one they are most interested in. This category was then the students’ focus as they finished the book. We use class time for writing the five- to 10-page final paper, and I encourage students to utilize their reading groups — and me — to go through outlines and drafts.

Many students pick one of the first two themes: Informed Consent and Medical Apartheid. This speaks to how my students related and were interested in the parts of the book that spoke directly to racial biases in medical care and research.

The criteria for these themes are prescribed in my directions to the students. Each section has four to five content-based criteria. Many of my students are not used to writing papers that blend both academic and conversational voices, and I have noticed that without content-specific criteria, my students tend to leave the science out of the science papers!

I have found the students are much more comfortable deeply explaining the family issues and generalizing the science content. But the papers that are written using the content-based criteria sheets reflect the understanding of the undeniable contributions to science from using Henrietta Lacks’ cells with the perspective and acknowledgement that the matriarch of an African American family is at the very center of these scientific advances and discussions.

Here is an excerpt from Desiree’ DuBoise’s paper:

The misuse of Henrietta Lacks’ cells, as well as the mistreatment of her family, was unethical. A big reason for the lack of information given to the Lacks family about the use of Henrietta’s cells was the fact that there was no precedent for how to go about using and profiting from cell research; it hadn’t been done before. The fact that the cells came from a poor Black woman only heightened the unlikelihood of doctors and researchers taking time out to meet the needs of the family (Johns Hopkins). The name of the owner of the cells went unknown for decades. The HeLa cells were thought to belong to either Henrietta Lacks, Helen Lane, or Helen Larson (Skloot, 1). Many have wondered why none of Henrietta’s family recognized her picture in articles written or knew about the studies using her cells. The Lacks family was poor and Black and living in the South; most of them had no more than a middle school education, so they wouldn’t have had access to articles and journals that were talking about the use of Henrietta’s cells.

Giving the cells a name and a story validated my students in a way that is not often seen in our science classrooms. Black students are frequently pushed out of classrooms in a multitude of ways; we need to seek ways to bring Black students’ voices into every subject, and particularly into STEM classes where Black students are underrepresented. Terri Watson, in an Education Week web series on “Black Girls and School Discipline,” said, “I think Black girls are seen as either invisible or they’re problematized.” Henrietta Lacks and the story of her cells exemplifies both. As a Black woman, Henrietta was separated into the “colored ward” of the hospital where her cells were seen as payment for her health care, and her cells were identified as hers only after decades of invisibility. Dedicating significant time to learn the story of a Black woman to whom biomedical research owes a great deal was time well spent. What we learned was more than the sum of Henrietta’s story and the science content of the book.