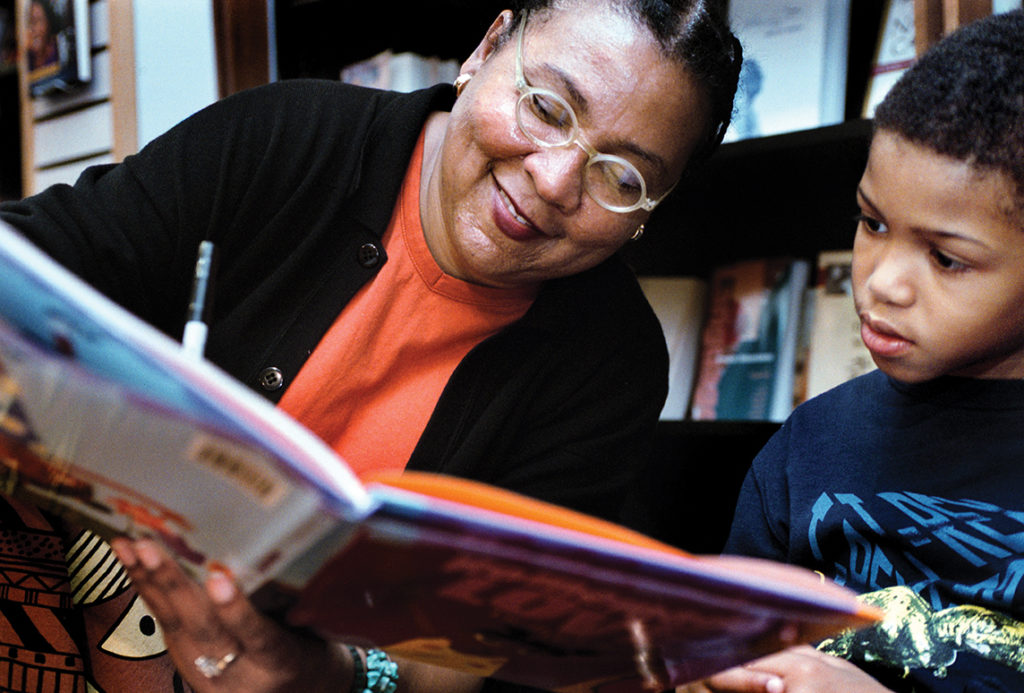

bell hooks: Learning as Revolution

bell hooks — brilliant, defiant, prophetic — died on Dec. 15, 2021. hooks’ influence on social justice education was so immense and so longstanding that we may not even recognize all the ways she touched our vision of the world — and our classrooms. In her too short life — she died at 69 — she wrote more than 40 books, including the influential work she began as an undergraduate at Stanford, the 1981 Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism.

hooks’ intellect was boundless, and she wrote seemingly about everything. But as her longtime friend and colleague Beverly Guy-Sheftall, professor of women’s studies at Spelman College, told Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!, “When I think about bell hooks, I think of her primarily as a teacher.”

hooks’ own radical education and vision of teaching began in her segregated elementary schools. As she wrote in her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom: “For Black folks teaching — educating — was fundamentally political because it was rooted in anti-racist struggle. Indeed, my all-Black grade schools became the location where I experienced learning as revolution.” She celebrated her Black teachers’ “messianic zeal to transform our minds and beings” — which, for her, stopped with school integration, when “knowledge was suddenly about information only. . . . It was no longer connected to anti-racist struggle.”

Those early experiences with teachers on a mission of justice and transformation left her with the conviction that “the classroom remains the most radical space of possibility. . . .”

“The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility.”

Building also off the work of Paulo Freire, hooks described education as “the practice of freedom,” with the aim of “critical consciousness,” which is not just contemplative but happens “in conjunction with collective political resistance.” She often used her own engagement with students to describe what critical teaching is — and is not. “When one provides an experience of learning that is challenging, possibly threatening, it is not entertainment, or necessarily a fun experience, though it can be.” The aim of our pedagogy, she insisted, “is to prepare students to live and act more fully in the world,” and to critique and work against “interlocking systems of domination,” which she named as imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy. These were not just picket sign slogans to hooks. In her writing, she demonstrated how these “interlocking systems” worked, and why one needed to attack all of these together, at once.

One thing we love about bell hooks’ work is how she was alert to the horrors of oppression and yet never reduced the oppressed to mere victims. People resist. People create. People find joy. Below, we excerpt a section from her “Language: Teaching New Worlds/New Words” from Teaching to Transgress, which exemplifies the suppleness of hooks’ thinking, her capacity to see the whole, to find hope, even amidst unimaginable brutality. The excerpt also reflects hooks’ lifelong concern with the centrality of language to making the world a better place — to talking back, to laying claim to a “legacy of defiance.”

— Rethinking Schools editors

***

“This is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you.” Adrienne Rich’s words. Then, when I first read these words, and now, they make me think of Standard English, of learning to speak against Black vernacular, against the ruptured and broken speech of a dispossessed and displaced people. Standard English is not the speech of exile. It is the language of conquest and domination. In the United States, it is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues, all those sounds of diverse, native communities we will never hear, the speech of the Gullah, Yiddish, and so many other unremembered tongues.

Standard English is not the speech of exile. It is the language of conquest and domination. In the United States, it is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues …

Reflecting on Adrienne Rich’s words, I know that it is not the English language that hurts me, but what the oppressors do with it, how they shape it to become a territory that limits and defines, how they make it a weapon that can shame, humiliate, colonize. Gloria Anzaldúa reminds us of this pain in Borderlands/La Frontera when she asserts, “So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language.” We have so little knowledge of how displaced, enslaved, or free Africans who came or were brought against their will to the United States felt about the loss of language, about learning English. Only as a woman did I begin to think about these Black people in relation to language, to think about their trauma as they were compelled to witness their language rendered meaningless with a colonizing European culture, where voices deemed foreign could not be spoken, were outlawed tongues, renegade speech. When I realize how long it has taken for white Americans to acknowledge diverse languages of Native Americans, to accept that the speech their ancestral colonizers declared was merely grunts or gibberish was indeed language, it is difficult not to hear in standard English always the sound of slaughter and conquest. I think now of the grief of displaced “homeless” Africans, forced to inhabit a world where they saw folks like themselves, inhabiting the same skin, the same condition, but who had no shared language to talk with one another, who needed “the oppressor’s language.” “This is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you.” When I imagine the terror of Africans on board slave ships, on auction blocks, inhabiting the unfamiliar architecture of plantations, I consider that this terror extended beyond fear of punishment, that it resided also in the anguish of hearing a language they could not comprehend. The very sound of English had to terrify. I think of Black people meeting one another in a space away from the diverse cultures and languages that distinguished them from one another, compelled by circumstance to find ways to speak with one another in a “new world” where blackness or the darkness of one’s skin and not language would become the space of bonding. How to remember, to reinvoke this terror. How to describe what it must have been like for Africans whose deepest bonds were historically forged in the place of shared speech to be transported abruptly to a world where the very sound of one’s mother tongue had no meaning.

I imagine them hearing spoken English as the oppressor’s language, yet I imagine them also realizing that this language would need to be possessed, taken, claimed as a space of resistance. I imagine that the moment they realized the oppressor’s language, seized and spoken by the tongues of the colonized, could be a space of bonding was joyous for in that recognition was the understanding that intimacy could be restored, that a culture of resistance could be formed that would make recovery from the trauma of enslavement possible. I imagine, then, Africans first hearing English as “the oppressor’s language” and then re-hearing it as a potential site of resistance. Learning English, learning to speak the alien tongue, was one way enslaved Africans began to reclaim their personal power within a context of domination. Possessing a shared language, Black folks could find again a way to make community, and a means to create the political solidarity necessary to resist.

Needing the oppressor’s language to speak with one another they nevertheless also reinvented, remade that language so that it would speak beyond the boundaries of conquest and domination. In the mouths of Black Africans in the so-called “new world,” English was altered, transformed, and became a different speech. Enslaved Black people took broken bits of English and made of them a counter-language. They put together their words in such a way that the colonizer had to rethink the meaning of English language. Though it has become common in contemporary culture to talk about the messages of resistance that emerged in the music created by slaves, particularly spirituals, less is said about the grammatical construction of sentences in these songs. Often, the English used in the song reflected the broken, ruptured world of the slave. When the slaves sang “nobody knows de trouble I see —” their use of the word “nobody” adds a richer meaning than if they had used the phrase “no one,” for it was the slave’s body that was the concrete site of suffering. And even as emancipated Black people sang spirituals, they did not change the language, the sentence structure, of our ancestors. For in the incorrect usage of words, in the incorrect placement of words, was a spirit of rebellion that claimed language as a site of resistance. Using English in a way that ruptured standard usage and meaning, so that white folks could often not understand Black speech, made English into more than the oppressor’s language.

The rupture of standard English enabled and enables rebellion and resistance.

An unbroken connection exists between the broken English of the displaced, enslaved African and the diverse Black vernacular speech Black folks use today. In both cases, the rupture of standard English enabled and enables rebellion and resistance. By transforming the oppressor’s language, making a culture of resistance, Black people created an intimate speech that could say far more than was permissible within the boundaries of standard English. The power of this speech is not simply that it enables resistance to white supremacy, but that it also forges a space for alternative cultural production and alternative epistemologies — different ways of thinking and knowing that were crucial to creating a counter-hegemonic worldview. It is absolutely essential that the revolutionary power of Black vernacular speech not be lost in contemporary culture. That power resides in the capacity of Black vernacular to intervene on the boundaries and limitations of standard English.

From the bell hooks book Teaching to Transgress. Reproduced with permission of the licensor through PLSclear.