Be Your Better Self

Writing to Embrace Humanity in a Time of Despair

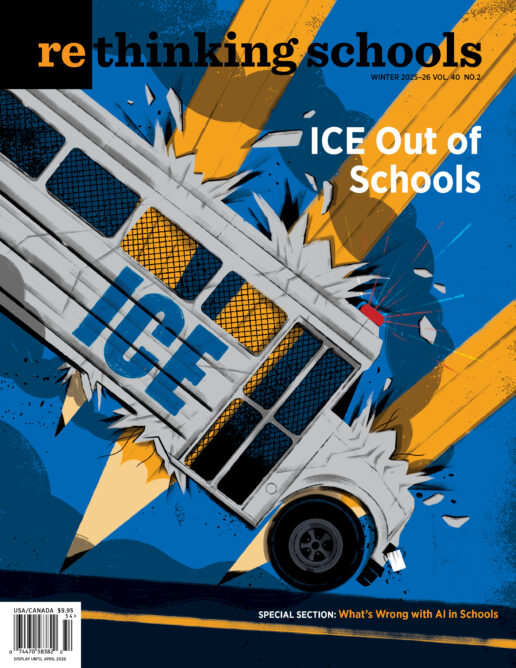

Illustrator: Simone Shin

Even in this ugly time of the bombing and starvation of the people of Gaza, the brutal ICE deportations, the resurrection of Confederate monuments, the termination of environmental and social protections, the theft and renaming of other people’s lands, I glory in the goodness and acts of courage and humanity that I encounter daily.

Take for example the Jewish students who chained themselves to Columbia University’s gates to protest the ICE jailing of Mahmoud Khalil, risking expulsion from the university to protect Khalil’s rights; or the Nashville folks who surrounded their neighbor’s car when ICE agents attempted to arrest them, bringing supplies and eventually forming a human chain from the car to the house. I revel in the news that another small town collectively resisted the tech industry’s massive expansion of data centers. Even the small courtesies of neighbors watering or mowing or taking care of pets seem endowed with a greater recognition that kindness and compassion are still alive. When I fall asleep at night and the news of the day has been filled with horror, I remind myself of these people and others who act with open-hearted generosity because I want to remember what’s good and right in the world.

That’s why I teach the “Be Your Better Self” narrative every year. Literature, history, and life abound with examples of characters — real and fictional — with moral integrity, whose willingness to reach out and help others serve as models for our students. This narrative has been a part of many units over the years, including a study of Enrique’s Journey about undocumented children crossing the border and the people who helped them survive the trip, and the reading of Grapes of Wrath, where hardship and bigheartedness held hands as the Joads traveled from Oklahoma to California. Most recently, this narrative was part of a unit studying the memoirs of incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II in the sophomore English class I co-taught with Dylan Leeman at Grant High School in Portland. In each unit, I tied the texts to contemporary issues that paralleled the worlds of the books: immigration, houselessness, deportations. In each variation of the unit, I asked the same questions as students read, watched news videos, or digested historical accounts: What are people risking and why? How are they acting as their better selves? What does it mean to act as your better self in this incident?

I curate the texts, the historical events, the personal writing, the poetry to stand on the side of justice. This means that in every unit, we defy the narrative that people are only self-interested, only greedy, only out for themselves. Yes, there are predators; yes, there are greedy people; yes, there are people who enrich themselves off others’ suffering. But I want my curriculum to celebrate that there are many more people, including those in the classroom, who act on behalf of others.

In this lesson, students examine their own lives for those moments when they acted as their better selves, reaching out to help others, standing up when it wasn’t popular or convenient, developing compassion and empathy in a time when outrageous acts of injustice abound. I use this prompt to help students recognize how they already act as their better selves and to practice seeing how people in their lives — friends and family members, teachers and coaches, classmates and cafeteria workers — provide evidence that kindness and solidarity surround them.

When the need arises, I want them to be prepared to act.

This narrative is a variation on similar writing prompts woven throughout my teaching — writing for justice, standing up for yourself and others, finding your voice, and more. Each iteration serves slightly different purposes and comes at student lives in new directions through different topics and models. It takes work to wrestle memories into writing, to remember actions that are routine or taken for granted or discounted and name them as acts of kindness, justice, courage. Each serves as a chance to invite students’ personal stories into the classroom as we work on literacy skills, attempt to create communities where students care about each other and the world, and help students build self-portraits as compassionate actors in their own lives.

“Anytime injustice exists, a world of kindness, generosity, and courage also exists, and this is the world we want to build.”

Launching the Narrative

Before we launched the narrative, Dylan and I talked about why we chose this topic. “As we finish our study about the enormous injustice unleashed on the Japanese American community, we want to remember that even during that horrific time, solidarity and generosity manifested themselves, sprouting up in camps, in homes, in kitchens, and on the streets. Today, our television screens and social media accounts are filled with armed ICE agents, mass firings, cutbacks for social protections but not war, the removal of books and curriculum that teach about racism, but we know that is not the whole story. People are filling the streets, banging on pots and pans, and keyboards demanding change. We want to remind ourselves that anytime injustice exists, a world of kindness, generosity, and courage also exists, and this is the world we want to build. In this assignment, we will write about our own stories of solidarity and kindness as we recall how when we act as our better selves, we contribute to that better world.”

After our preamble, we asked students to open a new page in their journals and to write this prompt: “In this narrative, write about a time when you or someone you know acted as their ‘better self.’ Sometimes we don’t. And that is another opportunity to write about what happened and your interior monologue about what you wish you had done differently — even a way to make amends.” Then we instruct them to make a chart with the headings “Others,” “Self,” and “Times I Wish I Had Acted Differently.”

Dylan and I each constructed a slide with the same chart, listing people in our lives who showed up as their better selves, times we were our better selves, and times we wish we had been our better selves. Before I shared my stories with students, I said, “Some of my stories may trigger memories for you. If that happens, jot notes in your chart. We want to build a big bank of ideas so you can choose the story you want to write for this assignment.” I started by talking about my mother taking my niece Kelly, who was frequently kicked out of school because in the 1970s her Tourette syndrome had not been diagnosed, to King Salmon Beach, where they practiced times tables and picked up seashells. I tell them how my parents always invited the members of the immigrant bachelor community they knew to our holiday dinners. I pause to ask students to think about people in their lives who act as their better self — maybe someone who they witnessed or maybe someone who helped them. After a few minutes of quiet reflection and noting, I asked a few students to tell their stories to help shake loose memories for their classmates.

When I shared from my own life, I discussed the easy, small ways I am my better self: picking up my older sister and taking her on outings, gardening in my daughter’s yard because she has difficulty bending and weeding, taking my grandson and his friend on outings on early release and grading days, so their parents can work, but I also included how I continue to teach and write articles and books and organize conferences with other teachers who want to build a social justice education movement. It’s easy to overlook the routine performances of kind actions in favor of big ones, so Dylan and I loaded our charts with both small moments as well as our community commitments.

We paused again for students to add to their lists. Then Dylan asked them to share some of their stories in their table groups. Dylan’s classroom has eight table groups with four students at each table. Although I love a circle classroom and individual desks, Dylan’s classroom and furniture are not built for that formation, but they function admirably for small group work. Dylan and I circled the room listening in as students talked, taking notes on whose stories might serve as catalysts for other students in case they didn’t volunteer. Often, we leaned in and asked the student to share their story with the class, so we didn’t put them on the spot later.

After students talked in their table groups, we encouraged a few volunteers to share with the class. Dominic described how his mother spotted their neighbor’s dead cat on the grassy knoll between the sidewalk and the street, another casualty of Portland’s exploding coyote population. “She scooped up the remains of the cat, so our neighbor wouldn’t have to see her pet torn apart.” Then she called the neighbor. Frank shared that his grandfather had a stroke, so when they ate dinner out, Frank noticed that his grandfather had difficulty maneuvering in the restaurant. Frank made his grandfather a cone from the soft serve machine and brought it to him. Aida’s mother sends money back to Eritrea every month to help family members. These are not huge stories, but they solidify the idea of looking out for other people and acting when the need arises.

Then we moved to the last round of listing. “Our final category asks us to think about times where you wish you had acted differently; thinking about these times is where change can erupt because now you acknowledge that you regret your behavior. For example, when my friend Judy died, I didn’t go to her funeral. My father had died a few years before Judy, and I found funerals traumatizing. When I look back, I regret my decision. I was close to Judy, close to her sister and mother. My presence would have been soothing for them. Today, I would have put my feelings aside and thought about Judy’s family. What would you do differently now and why? What was holding you back? What do you know now that you didn’t know then?”

This listing and discussing took most of a 90-minute class period. I like to end the class at this point because I know that as they go about the rest of their school day and evening, more ideas and memories will bubble up. In fact, before they file out the door at the end of the period, Dylan and I reminded them to let their subconscious do its work and return with more ideas at our next class period.

Looking at Models

During the next class period, we gave students time to add a few ideas in their charts or chat with a friend if they didn’t feel like they had a strong enough example to write about. We circled the room and conferenced with individual students who typically struggled to get started. We wanted to make sure that when we moved to a writing time, everyone had something to write about.

Dylan and I passed out a narrative written by a former student called “My Mother’s Big Heart.” According to Maya, her mother invited a friend and her child to stay in their already crowded apartment. I love this piece because Maya’s tone and observations about her mother’s “big heart” sound so authentic. She makes me laugh with her details about her apartment, the “guest” roommates, and her cat, and yet, even in her anger, her love and admiration of her mother shine through:

There’s a special kind of hate I reserve for my apartment. When I think about it too much I can almost physically feel all the anger I attach to this shitty two-room home gather itself up in my chest and it feels like if I don’t claw or gouge or tear it out with my hands I might explode into a million billion particles. It isn’t just the apartment that I’m angry about, but it’s what gets me started. My mom, on the other hand, has somehow managed to not completely despise where we live and has even gone as far as liking it. Inconceivable. I suppose she doesn’t have enough time to hate the apartment since she’s so busy worrying about money and groceries.

Maya’s depiction of the woman and her child who come to live with them demonstrates how to illuminate specific details to make a character come to life by noting her clothing, makeup, food and music choices in a quick, efficient manner:

I didn’t even like Anna that much. She was nice enough, and she had somewhat of a sense of humor, but she definitely wasn’t someone who’d be comfortable living with me and my mom and my little sister. She’s a peppy model/makeup artist whose whole wardrobe is made up of Nike clothes, and she listens to Katy Perry. The woman eats white bread for god’s sake. We, as a family, like listening to the Cure and have practically done away with bread altogether. Almost all our clothes are from Goodwill and makeup is scarce in our house.

During the remainder of the narrative, she describes the situation to her father:

“Yeah! I mean, I know I’m supposed to be empathetic and understanding and not completely angry about the fact that my mom did this when we have no money, no food, and no space. But I can’t help it. I really want them gone.”

“I know, Maya.” He laughed a little, “Believe me, I know. You and me don’t like being aroun’ people. But the thing you gotta understan’ is your mom’s got a f***in’ heart. A real big f***in’ heart. And she’ll do anythin’ for anyone.”

I always liked my dad’s lectures better than my mom’s. His always included cussing, which made them seem more down to earth. Not like he was talking at me, but with me.

Dylan and I read the piece out loud, using a reader’s theater style — both of us read the dialogue, and one of us read Maya’s interior monologue. After we finished reading, we asked students to talk about what actions showed Maya’s mother to be her better self. Students were quick to point out how her mother took in a friend, even though she was financially strapped.

We moved on to discuss the ways Maya developed the story. “Look back at the narrative and make margin notes about what you learned about each character: Maya, her mother, Anna, Maya’s father. When a narrative works, we want to ask ourselves: What did the writer do? In this narrative, what tools did Maya use to bring her characters to life? If we can identify those tools, we can apply them in our own writing.” After students examined the text again on their own, they discussed Maya’s writing strategies in their small groups. As table groups shared their findings in the large group, citing passages from the text, we created a list of writing tools they mentioned on the board: Interior monologue, details about clothes, food, music, and dialogue. “Add this list in your notebook,” I said, “because when you write your narrative, you may have a small story. Maya’s narrative can be summarized “My mother took in a friend.” You need to find ways to make the story come to life like Maya did. This is where the details, the interior monologue, and dialogue will become your friend.”

We read more narratives from previous students, so our class could see how others had approached the assignment. I know this sounds tedious, but preparation before the writing saves blank pages later. We looked back at how Maya opened with an interior monologue and how another student, Hannah, opened with dialogue. Xavier started his piece about being his better-self volunteer T-ball coach with a scene:

The kids were out of control: climbing trees, picking flowers, throwing dirt at each other. It’s not that I disliked them; more like it was difficult to coach them. Being a 12-year-old volunteer baseball coach wasn’t easy. The field wasn’t exactly a thrill either — muddy, gloomy, and full of potholes.

Although we don’t do every step — reviewing narrative openings or character development — with every assignment, we find that stacking models and strategies from writing to writing helps build our students’ capacity to become better writers.

The Writing

Students’ narratives were not characterized by grand acts, but they were filled with small deeds of generosity and kindness that when repeated can help students imagine a world in which people take care of each other. Kelsey’s narrative, for example, was about a time he bought his friend lunch:

“I don’t have enough money to buy anything,” he said.

“OK,” I said, then finished my order and then asked the worker how much it would cost for two of the orders and the amount was exactly how much money I had left, which was $22. I didn’t want to spend all the money I had left, but I also didn’t want him to watch Malcolm and me eat our food. I paid for it and when I got the food, Malcolm and Riley were already sitting at a booth waiting for me. I walked up to the booth with two boxes of meals in my right hand and two cups stacked on each other in my left hand.

While Riley was on his phone, I said, “Here’s your food, Bro, and here’s your drink.”

He looked up from his phone and said, “What, really? You actually got me food?” as he reached for the hamburger.

“Yes, Bro. I’m your best friend, right?” I said while handing him his food. He grabbed his stuff and got a drink and then we all ate and continued to reminisce about the past until we left 30 minutes later. Even though I spent the rest of my money, it was worth it because what kind of best friend am I not buying my friend food when he doesn’t have enough money and he’s hungry?

I want to live in a world where people ask themselves Kelsey’s question: What kind of friend would I be? At a time when the world feels hopeless and full of despair, paying for someone’s meal, coaching a T-ball team, taking in someone who needs shelter are the kinds of acts of generosity and kindness that build community instead of dividing it.

When most students have completed written drafts, they typed them into their Chromebooks. We wanted to see the progress from handwritten to typed. We also wanted authentic student work, not an AI-generated narrative. Of course, our lesson plan made this look linear, but absences, confusion, switching topics halfway through meant that while some finished drafting, others finished typing, and others began revising and color-highlighting their drafts for character development, setting, interior monologue, etc. We also asked them to put in marginal notes about changes they made — additions, deletions — when they moved from journal to Chromebook or when they color-highlighted and noticed a missing element.

Once most students had drafts, they shared their piece electronically with their table mates. “First, use the comment feature to tell your partners what you loved about their pieces — specifically noticing character development or language or other writing strategies. Also, highlight any places where you got confused or wanted more information and leave a comment, suggestion, or question to help them improve their draft. When you have finished reviewing your table mates’ drafts, write in your notebook about what you learned about how your friends acted as their better selves. What do we learn about what it means to be your better self?”

At a time when people are rounded up because of their accents or skin color, when people are denied their rights because they are trans, when people are denied health care because they are poor, we want students to learn the myriad ways their classmates, their families, and they themselves embrace others’ humanity. Each time students identify an action that they have taken or even one that they wish they had done differently, they begin building a narrative of themselves as the kind of person who refuses to stand by while others are mistreated, a person who offers assistance and solace to others. When despair creeps in, let’s remind our students that a better world is possible.