As a Teacher and a Daughter: The Impact of Islamophobia

Nidal El-Khairy

Like many, I watched in shock as the terror attacks unfolded in Paris last November. ISIS, the same group that had killed 43 innocent people in a double suicide bombing in Lebanon the day before, was now attacking Parisians. I checked Facebook to see if my Parisian friends were safe and noticed two things: First, several friends had messaged me to ask if my friends in Paris were safe (I lived there in 2008). Second, there was a feature enabled called the Facebook Safety Check that lets users mark themselves “safe” after an attack, earthquake, or other disaster.

I was relieved to know that my friends were OK, but I also felt the weight of the questions that followed in my mind: Why didn’t my family have access to the same safety feature following the bombing in Lebanon? Are some lives more worthy of mourning?

And as an educator, I couldn’t help but wonder: What impact would the media’s asymmetric attention have on our students who come from countries where this type of violence—whether from U.S. drones, seemingly endless war, or groups like ISIS—has recently been a frequent reality? As one student said: “One of my teachers addressed the fact that Paris was under attack, but didn’t mention anything about the rest of the world. It would have helped a lot if she addressed what was going on all around the world.”

Students whose families are from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Tunisia, Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria, or other non-Western countries that have experienced terrorist attacks come to class and are part of a collective mourning for French people, knowing full well that similar attacks in their own countries have not received equivalent attention in their schools. It is almost impossible for these students not to draw the conclusion: The death of people who are racialized and/or look like me are virtually ignored—in the media and at school.

When I asked a cousin, 19-year-old Jasmine Bardouh, how she felt on the Monday after the terrorist attacks in Paris, she responded: “Honestly, I had a mixture of feelings running through me. I was sad, frustrated, and scared. Sad because of all the innocent people who died, scared because of all the blame Islam was going to get, and worried that people would target me because of the horrible crimes committed in the name of Islam. Most of all, I was frustrated because of all the uneducated people online cherry-picking quotes that sound violent from the Qur’an and posting them on social media. That caused even more fear and misconceptions about Islam, as if there wasn’t enough confusion and hate already. I was also frustrated because the same week as the Paris attack, other countries, including Lebanon, also had fatal terrorist attacks, yet got almost no mainstream media coverage. This made me feel as though the blood of some people is considered more valuable then others, even though we are all human beings. Feeling as though you are less because of your religion and race is a horrible feeling.”

On the Monday after the Paris attacks, classrooms across the country were lit up with discussions about what had transpired in Paris. These are valuable discussions, but they must be facilitated carefully if we are to ensure that all students, regardless of their faith or ancestral origin, feel safe in our classrooms. As Jasmine’s 16-year-old sister Amel said: “The week after the attack, there were posters all over school saying ‘Pray for Paris’ but I didn’t see one poster that had anything written about Lebanon or Burma or Syria.”

According to Elie Fares, a Lebanese doctor interviewed by the New Yorker: “When my people died, no country bothered to light up its landmarks in the colors of their flag. . . . When my people died, they did not send the world into mourning. Their death was but an irrelevant fleck along the international news cycle, something that happens in those parts of the world.”

This asymmetry of care and concerns is but one of the many faces of Islamophobia.

“I’m Afraid to Leave the House in My Hijab.”

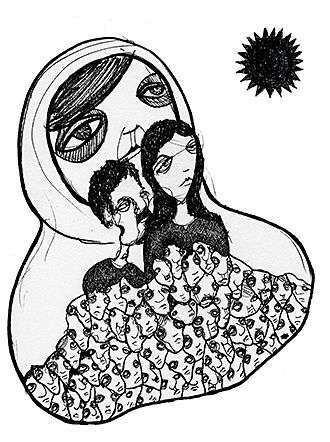

This article is dedicated to my mother. She is a remarkable French and resource room teacher. She is also a tireless advocate for social justice in her community. Her efforts include running a refugee welcoming committee and founding a group that works to build interfaith awareness.

The day after the Paris attacks, my mom and I were going to go to the mall. As I was getting ready to go, I could sense that she wasn’t in the mood. Thinking she was worried about our family in Lebanon and the rising threat of ISIS, I asked her what was bothering her.

What she said was so disturbing and shocking: “I am afraid to leave the house in my hijab.”

The person I look up to most didn’t want to leave the house because she felt people would associate her with the terrorist attacks in Paris? I couldn’t believe it. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about my mother’s words, and the paradox of her being associated with ISIS, the very group that had put her own family in danger only a few days earlier.

This is a direct effect of Islamophobia: the drastic, ignorant misinformation that links people like my mother with those who carried out the attacks. An oversimplification that leaves someone like my mother, who faces the same fears as the Parisians, uncomforted by and even excluded from the solidarity of public mourning that is the privilege of nonracialized groups.

If a woman as strong and politically centered as my mother can feel shame after a terror attack, many of our students and their families are likely to feel the same way. When I asked 19-year-old Hania how she felt after the attacks, she said: “I felt like I had to go on a mission to prove that I was against these attacks: ‘Yes, I’m against people getting killed.’ I felt like I had to prove that I’m a decent human being.”

Islamophobia spikes after terror attacks are carried out in the name of Islam. According to an article by Andy Campbell for the Huffington Post in December 2015, hate crimes against Muslims in the United States have tripled since the attacks in Paris. Canada is no exception. For example, in the days following the Parisian attacks, a Muslim woman was attacked by two men as she picked up her children from a Toronto school. They pulled off her hijab, punched her, stole her phone, called her a “terrorist” and told her to “go back to your own country.” This is not an isolated instance; walking down the street has become an even more charged activity for Muslims.

It seems absurd to associate the KKK with Christianity, but the same distinction is rarely made for Muslims. According to student Wajahat Ali in Mislabeled: The Impact of School Bullying and Discrimination on California Muslim Students, “Your existence is always interrogated, investigated, and questioned.”

What Can Teachers Do?

As educators, we know that our words carry a powerful weight. Although we can’t control how the media portrays Muslim people, we can encourage our students to think critically about the messages that they receive from the media. We must also protect our students from classroom debates where they are singled out and feel like they have to defend their faith. As 12-year-old Farah told the Guardian, “Before the attacks I was mostly treated like everyone else. But now I’m having to answer questions about my religion and the actions of people I don’t even know. It’s a lot of pressure. I mean, I’m only 12.” Acknowledging one terror attack while ignoring others, debating whether or not Islam is inherently a violent religion, or asking Muslim students to defend their faith can result in Muslim students and their families feeling even more alienated in a society that already stigmatizes them.

One way to mitigate the impact of Islamophobia is to teach our students about it. We need to expose and critique the myths being constructed about Islam all around them in the media, in public discourse, and even in their classrooms.

For example, I teach at an alternative program in Vancouver for young parents from ages 13 to 19. Many of my students are raising their children independently while going to school. They know all too well the need to think critically and challenge stereotypes.

In the week after the Paris attacks, I asked my students if they had been following the news and encouraged them to discuss what had transpired over the weekend and how it was portrayed in the media. After expressing sorrow and outrage about the attack, they made the connection between stereotypes they face as young mothers and stereotypes that Muslims face. Earlier in the year, we had watched Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Single Stories” TED Talk. They recalled Adichie’s talk, and noted that the media coverage of the Paris attacks reinforced the “single stories” we hear about Muslims.

I often tell stories about my father so that I can humanize and debunk myths about Muslim men. For example, during a unit on healthy relationships, I told my students how he worked to put my mother through school so that she would never have to be dependent on him.

Moving past my own classroom, I’m in the anti-racist action group of my union, the British Columbia Teacher’s Federation (BCTF). We are a social justice union, so after the Paris attacks, I emailed our social justice director and asked if I could work on some lesson plans to help teachers broach the subject of Islamophobia in their classrooms. The union supported me to create a primary and intermediate lesson plan as well as a resource list for teachers (see Other Resources).

As my wise friend and fellow teacher Ryan Cho recently reminded me: “It is hard to recognize your historical moment when you are in it.” As anti-Muslim sentiments continue to deepen, particularly after recent terror attacks and the rise of Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim campaign, we must use our position as educators to ensure that our students have a critical eye and are able to separate the violent actions of ISIS from the lives of the one billion Muslims who exist across the world.

We cannot leave our students in a situation in which they have to defend themselves in the face of racism and religious discrimination. We can, and must, draw the ties between Islamophobia and other forms of intolerance. This is a crucial moment in history: We can choose to be true allies and fulfill our commitments to make our school communities nurturing spaces for all students, teachers, parents, and staff. The need for self-reflection has never been greater.

References

- Chin, Jessica. Nov. 17, 2015. “Muslim Woman Attacked While Picking Up Kids from Toronto School.” Huffington Post Canada. huffingtonpost.ca.

- Council on American-Islamic Relations. 2015. Mislabeled: The Impact of School Bullying and Discrimination on California Muslim Students. Download PDF.

- Irshad, Gazala. Dec. 21, 2015. “How Anti-Muslim Sentiment Plays Out in Classrooms Across the U.S.” The Guardian. theguardian.com.

Other Resources

- Elbardouh, Nassim. 2015. Islamophobia Lesson, Part I. Download PDF.

- Elbardouh, Nassim. 2015. Islamophobia Lesson, Part II. Download PDF.

These lessons for high school students were created for the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation. They incorporate a number of the resources listed here: - Adichie, Chimamanda. 2009. “The Danger of a Single Story.” TEDGlobal. ted.com.

Our lives, our cultures, are composed of many overlapping stories. Novelist Chimamanda Adichie describes how she found her authentic cultural voice—and warns that if we hear only a single story about another person or country, we risk a critical misunderstanding. - Dazed. 2015. Do You Know Who I Am? How It Feels to Be a Young British Muslim in 2015. Video directed by Camilla Mathis. youtube.com.

- The Narcicyst with Shadia Mansour. 2015. “Hamdulillah.” Music video. youtube.com.

This video is a global collaborative effort by 10 photographers—from London to Lebanon, Cairo to Canada, Abu Dhabi to the United States—to represent the diversity of Muslims worldwide. Images include DJs, MCs, poets, architects, teachers, doctors, parents, and children. - Rao, Sameer. Oct. 20, 2015. “#DoIMatterNow Campaign Promotes Indigenous-Muslim Solidarity in Canada.” ColorLines. colorlines.com.

The #DoIMatterNow campaign was started by Inuit women in Canada who donned makeshift niqabs and took pictures decrying the systematic disenfranchisement of Native people while expressing solidarity with Muslim women. - Bazian, Hatem, and and Maxwell Leung, eds. Fall 2015. Islamophobia Studies Journal. Download PDF

This journal is a helpful resource for educators seeking more background information.