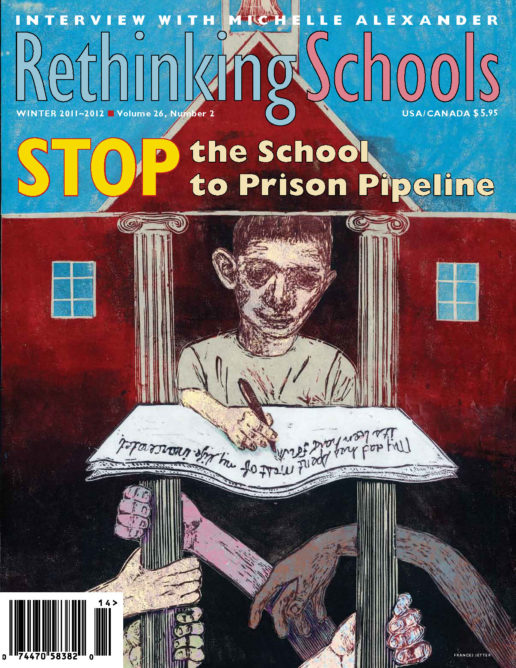

Preview of Article:

Arresting Development

Zero tolerance and the criminalization of children

Illustrator: Alec Icky Dunn

A week before classes ended last spring, 13-year-old Diana Nava was waiting with her mother, Modesto, for the Los Angeles city bus that goes near her school. Even though her mother had awakened Diana early, she was behind schedule. An LA police officer patrolling for truants spotted them at the bus stop and gave Diana a ticket for violating the city’s daytime curfew. “My mother said, ‘She’s on her way to school’ but the officer said it didn’t matter.” For being late, Nava and her mother would have to go to court and face a $250 fine, a loss in time and money they could ill afford.

Nava was one of a dozen LA students who testified in August 2011 about their experiences with the truancy sweeps by LAPD officers and LA school police that have resulted in nearly 50,000 tickets since 2004. The hearing was called by Judge Michael Nash, head of LA’s juvenile court system, in response to five years of organizing by parents, students, and youth advocates against what they see as unfair and ineffective policies. Supposedly designed to improve student attendance, this aggressive truancy policing has discouraged students from going to class and often pushes them to drop out and into harm’s way. “Truancy tickets play a role in the school-to-prison pipeline,” said student Cinthia Gonzalez at the hearing. “Students are being brought up in an environment that is a pre-prisoning of youth.”

Jose Gallego’s story is a case in point. The 23-year-old explained: “I’m a high school dropout. I was supposed to graduate in 2008, but I missed a few days of school because my parents were going through a hard time. They kicked me out of school. So, then I started selling CDs downtown. I was arrested for selling CDs, I was locked up, and I got out with a whole different perspective. I never had been in juvenile detention. I didn’t know what to do. I started selling drugs. Now I’m lost. I’ve got a little brother and a little sister, they don’t look up to me anymore. I’m a two-time convicted felon. It’s hard for me to get a job.”

Los Angeles is not the only place where heavy-handed policing has become a problem that advocates say puts students at risk of dropping out. From New York to Florida to Texas, the combination of zero tolerance policies and the increased role of police—in schools and on the streets—has led to an alarming number of suspensions, expulsions, and contact of ever-younger children with the criminal justice system.

How did we get to this point?