Preview of Article:

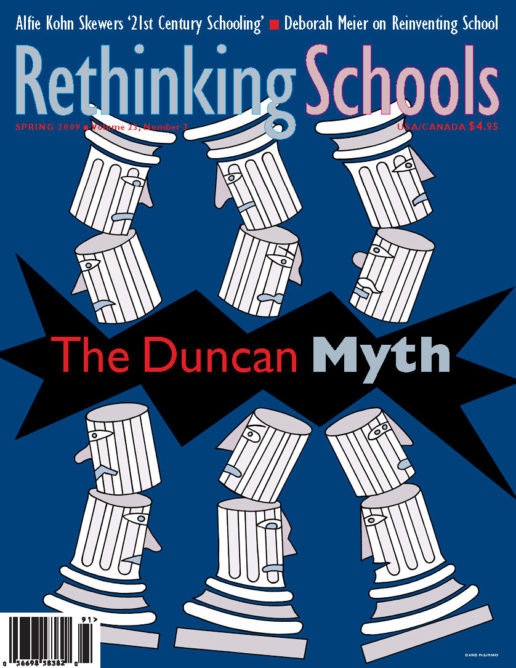

Arne Duncan and the Chicago Success Story: Myth or Reality?

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

When ex-President Bush was elected in 2000, he brought with him former Houston Superintendent of Education Rod Paige to be Secretary of Education. He also brought the “Texas miracle” — supposedly increased test scores attributed to Texas’ strict accountability system. All eyes smiled on Texas as those measures quickly became part of No Child Left Behind, passed into law in 2001 by both political parties. Before the end of Bush’s first term, Paige would leave in disgrace, thanks to revelations of cooked scores, forced-out students, and other barely legal means of inflating test results.

With the appointment by Barack Obama of Arne Duncan — a noneducator from the business sector who was Chicago’s “chief executive officer” — as U.S. Secretary of Education, this phenomenon may repeat itself. For the past several years, Chicago’s model of school closings and education privatization has received national attention as another beacon of urban education reform. This may have special relevance as the number of schools “identified for improvement” by NCLB criteria grows, numbering 11,547 nationally in the 2007-08 school year. Other school districts across the U.S. have already undertaken programs similar to Chicago’s — New Orleans, in the wake of Katrina, has had a massive privatization of schools (see the special report on New Orleans in Rethinking Schools Vol. 21, No. 1), New York City has proposed closing and phasing out schools using criteria similar to Chicago’s (e.g., test scores), and Philadelphia has followed suit as well, with a number of new charter schools. As Chicago Mayor Daley said in a 2006 press conference, “Together, in 12 years we have taken the Chicago Public School system from the worst in the nation to the national model for urban school reform.” The Chicago Commercial Club’s Renaissance Schools Fund Symposium, “Free to Choose, Free to Succeed: The New Market in Public Education,” in May 2008, was attended by school officials from 15 states. The headline for a Dec. 30 article in the Washington Post claimed, “Chicago School Reform Could Be a U.S. Model.” And outgoing Secretary Margaret Spellings praised Duncan as a national leader for his teacher incentive pay program.