Preview of Article:

“Aren’t You on the Parent Listserv?”

Working for equitable family involvement in a dual-immersion elementary school

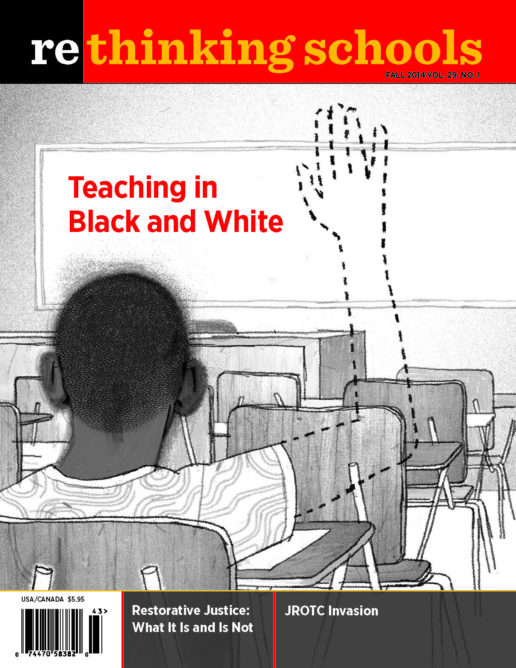

Illustrator: Bec Young

When I visited my current school in San Francisco to do a demo lesson in a dual-immersion classroom, I was excited by the diversity that I saw. The bilingual Oakland school I had worked in before had been anything but diverse, either racially or socio-economically—98 percent of the students identified as Latina/o, 95 percent were eligible for free or reduced lunch, and about 86 percent were classified as English language learners. Everywhere it seemed that segregation in public schools was becoming more entrenched. Yet here I was, awkwardly clutching my bag of demo lesson materials, facing a sea of kindergarten faces that seemed to buck this trend. There were Latina/o students, African American students, white students, all chattering away in Spanish. I was elated. Could I have found a place where the interests and needs of many different populations converged—a public school that worked for everyone?

Then, in September, after starting my new job as a kindergarten teacher, I went to a PTA meeting. The parents at the meeting were excited to be there and dedicated to making the school a place that would serve their children. They were also almost entirely white, and—as I would learn as I got to know parents personally in our small school community—almost entirely middle- or upper-middle-class native English speakers. On paper, our school was about 50 percent Latina/o and 20 percent African American. Yet, in that first PTA meeting, with about 40 people in attendance, I saw only a handful of Latina/o parents. There were no African American families present. Later in the year, one African American family did frequently attend, but the number of Latina/o parents who came and used the interpretation services quickly dropped to zero. In addition, most of the parents involved came from the Spanish immersion track. The general education track, composed argely of students of color, was essentially unrepresented.

At my previous school, where the majority of families were recent immigrants, I had seen the positive impact of parents who were empowered to advocate for their children, although most were not native English speakers and many were unfamiliar with the structures of the local school system. The English Learner Advisory Committee (ELAC) and School Site Council (SSC), the two required decision-making bodies with parent members, were run in Spanish by parents, and there was no such thing as low family involvement due to the demographics of the community. Parents felt at home and knew that neither their native language nor unfamiliarity with the school system would be barriers to articipation. Where were these families at my current school?

As I watched the PTA set fundraising goals, choose art enrichment programs, fund teaching positions, allocate money for books, determine what technology would be purchased, and select what types of paraprofessionals to hire, I became more and more concerned about whose voices ere being heard and whose children were being advocated for.

I quickly began to see these inequities play out in my own classroom. The three mothers who signed up to be room parents were middle-class professionals, all white native English speakers. They all knew each other because their children had gone to the same bilingual preschool. The majority of families at Back to School Night were also white and English speaking. In the first two weeks, emails were sent, Google docs created, and listservs were joined, all in English. One half of the classroom parent community got to work, humming right along on rails that issed the other half by miles.

This was worrisome for a number of reasons. At my school, the stakes for parent participation are high because of the sorts of decisions the parent groups are responsible for. The PTA and SSC manage the budget, and the PTA brings in more than $100,000 a year. These groups work together to decide everything from whether or not there should be combination classes to what types of after-school intervention are vailable to struggling students, from field trip budgets to whether there are art enrichment classes and for whom.

I was also concerned about this pattern for another reason: As teachers we see the direct impact of parent involvement on our students—families who feel comfortable with and included in the school community can advocate for their children’s needs, check in about their progress, get tips on how to help them at home, and stay informed about programs and opportunities that will be beneficial to their family. Attendance goes up and children benefit from seeing their parents as involved in their school community. When parents and teachers talk, children’s behavior and motivation improves as they begin to understand the ways their home and school worlds are connected. I was going to have to do something quickly or risk losing those benefits for many of my students, and instead see my classroom duplicate the same sort of inequitable parent involvement that I saw at that first PTA meeting. The story of how I attempted to shift those dynamics is one of tiny victories, but it also shows how what we do in our own classrooms to address equity in parent participation can ripple out to affect the school as a whole.