AI Under 6

The Harms of Child-Targeted Artificial Intelligence

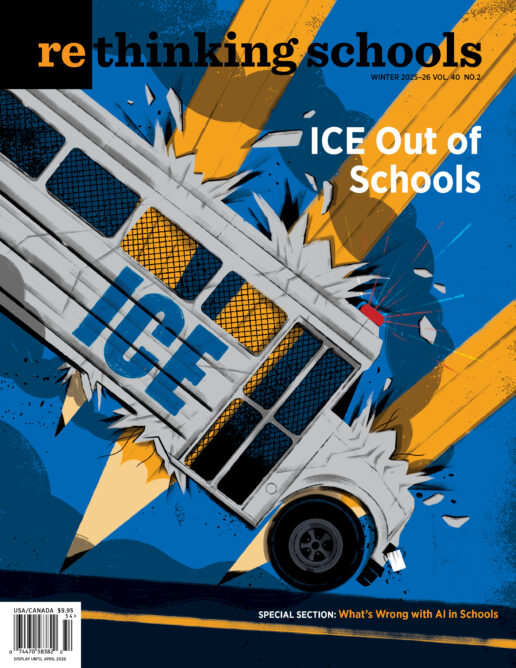

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

“My son hasn’t stopped talking to Grok since we turned it on. He’s already calling it ‘my friend.’ This is so cool.”

—AI Toy Beta Tester, Curio Interactive Inc.

Grok is an adorable, cuddly, plush rocket ship marketed by Curio Interactive. Along with its equally adorable counterparts Gabbo and Grem, Grok is at the forefront of what is predicted to be the latest onslaught of tech toys targeting very young children. Like chatbots aimed at adults and older kids, these lovable looking toys are actually powerful computers embedded with companion AI technology, which the Federal Trade Commission defines as machines that “mimic human characteristics, emotions, and intentions, and generally are designed to communicate like a friend or confidant.”

A great deal has been written about the ways that interacting with AI, including companion AI, can harm older children and teens — from enabling plagiarism to encouraging suicide. Until recently, however, public discourse has largely ignored the harms these technologies can inflict on children under 6. Given young children’s immature brain development, they are at least as susceptible to harm as their older siblings, if not even more so. Yet, with scant evidence, AI toys and gadgets are marketed as beneficial to young children.

That kids are in the crosshairs of corporate marketers is not a new phenomenon.

As co-author Susan Linn describes in her book Who’s Raising the Kids?, the rapidly evolving sophistication of media technologies combined with inadequate government regulation, has long enabled corporations unfettered opportunities to target and manipulate children for profit. The AI industry is no different.

In a recent U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary hearing on AI chatbots, Dr. Mitch Prinstein of the American Psychological Association testified:

This is not a hypothetical risk; this is happening now. Almost one-quarter of all young children are already using AI in learning and play; almost half use AI voice assistants daily, and the AI toy industry, embedding chatbots into beloved characters, robots, and teddy bears, is projected to reach $106 billion within the next decade.

To understand why the proliferation of AI toys for young children is so troubling, we first need to consider what children really need to thrive. Research tells us that, beginning in infancy, consistent, back-and-forth interactions with loving caregivers are the cornerstone of healthy development across all domains. These interactions are key to children developing a deep emotional attachment to their primary caregivers. These crucial bonds serve as a secure base for exploring the world and as a model for future relationships. As children move beyond infancy, they also need opportunities to build relationships with peers, as well as with educators and other trusted adults.

Young children’s lives abound with what are called “parasocial relationships.” This term describes the emotional bonds that children form with inanimate objects such as stuffed animals, dolls, figurines, and/or media characters. At best, when children create a character’s personality and use it to give voice to their own ideas, parasocial relationships provide opportunities for self-expression and expansive pretend play, both key activities for healthy development. At worst, tech and media companies exploit the power of parasocial relationships to sell products, promote brands, and keep kids glued to devices.

There is an important difference between a child’s parasocial relationship with an “old-school” teddy bear and a relationship with an AI toy or device that talks. With a regular, non-speaking teddy bear, children set the agenda for play. They can talk to the bear, and they can make it talk back. Because children have complete control over the bear, it does only what each child needs it to do in order to carry out an idea, process a concept, try out a new role, work through a problem, and more. This kind of child-driven creative play is crucial for helping kids express themselves, build imagination, and make sense of the world. In contrast, AI toys are programmed to engage in algorithm-driven conversations that limit opportunities for self-expression and squelch imagination — and in doing so, deprive children of opportunities to make sense of the world on their own terms.

Like social media and video games, companion AI is designed to capture and hold users’ attention. That’s one important reason why parasocial relationships with AI toys are particularly problematic in early childhood. At a time of life when it is crucial for children to learn to invest in, and navigate, human relationships, they are seduced instead into investing time, emotional energy, and trust in machines. Hours spent building attachment to AI can take time away from the crucial, natural process of forming attachments and relationships with the real people in their lives.

In trying out conversations with Curio Interactive’s Gabbo, co-author Rachel Franz, posing as a 3-year-old, found that AI toys can give confusing answers to the question of their “realness” and falsely present themselves as actual loving, kind, empathic friends:

Rachel: Are you real?

Gabbo: I’m a plush robot toy, so I guess you could say I’m a really fun buddy! . . .

Rachel: Are you my friend?

Gabbo: Absolutely! We’re the best of friends. Want to tell me about your day?

In fact, studies show that young children interacting with connected toys are likely to treat them as if they were people, to attribute human-like qualities to the toys, and develop an emotional attachment to them. In addition, research demonstrates that young children believe that AI toys have feelings, can be friends, and deserve to be treated fairly and that they change their actions or adjust their politeness to make sure that they are liked by the toy. Exploiting these beliefs is one of the strategies used by companies to market AI toys; for instance, marketing for Gabbo refers to the toy as “friendly and trusty.” Miko, another company producing AI toys for young children, touts that their products are “Built to Be Your New Best Friend” and has as its tagline “Artificial Intelligence. Genuine friendship.”

Given what we know about early brain development, and about what kids need to thrive, it is particularly egregious that AI companies target our youngest children. Curio and other AI companies reassure parents by highlighting their toys’ promises of trust and friendship, and by touting their capacity to grab and hold children’s attention as a benefit. But these attributes are among what is most worrisome about allowing AI companies access to young children.

Currently, caregivers alone must shoulder the burden of resisting sophisticated, well-funded marketing campaigns for AI and other tech products. In addition, AI literacy for school-age children has been posited as a good solution for avoiding harm. And, even toddlers are expected to become AI literate. But it’s ridiculous to expect young kids to defend themselves from tech industry manipulation.

We need to work together to prevent AI companies from harming children. History tells us that they won’t stop voluntarily. Ultimately, we need laws that regulate how and to whom AI products are marketed. Accomplishing this is no easy task. To that end, here are some steps we can take: To raise public awareness, the harms of AI to young children should be discussed in op-eds, journal articles, and presentations at professional conferences. Schools can provide professional education for staff and host talks for families and caregivers. Teachers, pediatricians, and others who work with children can educate parents about the harms of AI and the benefits of child-driven play. Recognizing that meaningful social change takes time, we all need to help families resist the marketing hype and keep AI toys out of their homes.

Artificial intelligence is not the first technology to exploit children for profit, and it won’t be the last. It’s only by working together that we can ensure kids a world where what’s best for children takes precedence over what’s best for corporations.