Activism Is Good Teaching

Reclaiming the profession

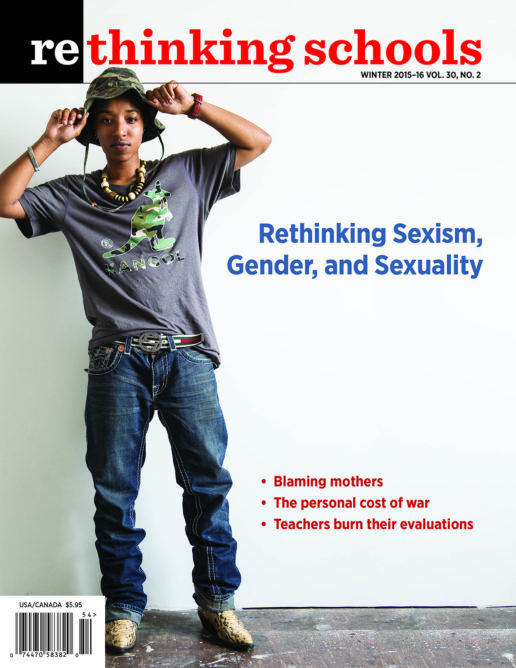

It was a sunny afternoon in May 2015. Several dozen Albuquerque Public School (APS) teachers gathered around a metal garbage can outside district headquarters just a few minutes before the final school board meeting of the year. As local news cameras rolled, the teachers came forward one by one to burn their end-of-year evaluations. Like many states across the United States, New Mexico has adopted a value-added model of teacher evaluations, basing 50 percent of the overall score on student test scores. Whether rated as “minimally effective” or “exemplary,” the teachers individually and collectively made a powerful case for why their evaluations were arbitrary, unreliable, and deeply damaging to the profession of teaching.

As I watched from sidelines, I recognized Michelle Perez and Amanda Short, two teachers from High Desert Elementary, a high-poverty school rated “F” by the state of New Mexico. The event, which Michelle helped organize, occurred at the end of a tumultuous school year, characterized by drastic decreases in teacher autonomy and a growing culture of surveillance and fear. Michelle worked on the event because “these evaluations are not a reflection of a teacher’s abilities and should not determine our worth as professionals.” She wanted to create a way teachers could share their frustration with the public as well as with the local school board, who, for the most part, have been complicit in the policies mandated by the New Mexico Public Education Department (PED).

High Desert Elementary School is a Title I school with 100 percent of its students qualifying for free or reduced-price breakfast and lunch. The diversity of the school’s population is representative of the state: 5 percent African American, 30 percent white, 55 percent Latina/o and 10 percent Native American; 33 percent are English language learners and 29 percent qualify for special education. Students live in Section 8 housing, in motels along the interstate, and in homes close to the local university. Throughout their teaching careers at the school, Michelle and Amanda have noticed a decline in diversity due to decreasing enrollment among middle-class families, a demographic shift that can be attributed to the poor grades the school has received.

Michelle and Amanda, who teach 2nd and 4th grade respectively, are veteran teachers with an impressive array of credentials. Michelle has a master’s and endorsement in reading instruction and helped write the district’s 2nd-grade math curriculum. Amanda is National Board certified. Both teachers have spent their careers at High Desert Elementary in part because of a desire to serve children from historically marginalized backgrounds. Last spring, both received overall evaluations of “minimally effective” on the state’s evaluation rubric. Their principal gave them failing grades in the category of “professionalism” due to their ongoing activism against high-stakes accountability policies.

For example, on Amanda’s evaluation, the principal wrote: “Because she is respected by the adults that she works with, her dissatisfaction with requirements has been shared with others resulting in similar actions. . . . I feel that she has had a negative impact on the culture of [High Desert] this year” and “Ms. Short has been very vocal in speaking out against mandates from the district level, which has led to discord in the building and which has even moved to the district level.”

A School-University Collaboration

My colleagues from the university, Rebecca Sánchez and Kersti Tyson, and I met Michelle and Amanda through a school-university partnership that originated with plans for a curriculum project on Japanese lesson study. Soon, however, the restrictive policy environment at every level of education compelled us to join forces to resist. Over the past two years, we have worked collaboratively to oppose key mandates, march on the state capitol in support of teacher autonomy, and design classroom initiatives based on authentic inquiry and critical engagement with elementary students.

As educators who work at various points across the P-20 spectrum, we have all noticed a decline in teacher autonomy and a notable absence of teachers’ voices in shaping policy. As this phenomenon has intensified, there is a growing need for teachers to reclaim our profession though activism. Although schools, administrators, districts, and the state increasingly define professionalism as a willingness to comply with mandates, no matter how problematic, we offer a different definition: professionalism as activism.

Professionalism as activism recognizes that we enter our role as teachers in a democratic society with a set of commitments and responsibilities to advocate for children and for ourselves as educators. That means we must speak against policies and leadership decisions that undermine our work and devalue our expertise about children and learning. As one popular protest sign states, “You cannot test your way to a great education, you teach your way there.” Amanda and Michelle were marked down for speaking up, but we see their acts of opposition and resistance as a necessary means of preserving intellectual integrity and democratic principles.

Professionalism as activism, then, is characterized by action to defend and promote meaningful instruction and collaboration among teachers, action to inform families about current reform initiatives and their rights, and action as protesters against unsound policies that compromise the integrity of teaching and learning in our public schools.

Professionalism can be used as a class marker—a way to divide teachers from teaching assistants, cafeteria workers, and others whose work is integral to creating schools that serve all students’ needs. We recognize this as problematic. Yet we use the term professionalism in this article to argue that teaching should have validity as a life’s work, and that in the current sociopolitical context, professionalism includes fighting for good education.

Bubble Sheets or Meaningful Assessment?

The district allocated more than 40 days in the spring semester for PARCC (one version of the Common Core test) alone. At High Desert, not only do teachers administer multiple district and state assessments, they are also required to spend valuable planning time filling in forms and submitting “data” for schoolwide analysis. When teachers were asked this year to conduct yet another districtwide assessment, complete with manual entry of data into bubble sheets, Michelle and Amanda gave the tests but delayed completing the bubble sheets while they asked the district how it planned to use the assessment. Amanda emailed the district’s data department multiple times, asking them to produce the document stating teachers were required to administer these assessments. Michelle contacted the district and superintendent seeking more information about the purpose of the assessment. The district was only able to produce one document, which said the English/Language Arts district tests were “recommended” (not required); there was nothing about the math test. Both teachers believed that bubbling in sheets with data that ultimately does not inform instruction is a detrimental use of their time.

In previous years, both teachers used their collaborative planning time to design performance assessments. One powerful example from Amanda’s class was an open house culminating a unit on New Mexico history. Because Amanda’s class included students who identify as Native American, Chicana/o, and Mexican, she wanted to ensure that each child’s history was included in the unit as they learned about the Spanish conquest of Mexico/New Mexico and discussed how this drastically changed the lives of the cultures who had lived there for centuries. So, for example, students first encountered the story of the Spanish arrival at Zuni Pueblo through a video shown at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center that highlights the perspective of the Zuni people. Students then read a text from the social studies curriculum describing the same event from a mainstream perspective. Amanda prompted students to compare the two stories and discuss whose stories were privileged and whose were silenced in the social studies curriculum. At the final open house, students presented on the history, voices, and critical perspectives they had learned. This assessment offered all students multiple ways of showing their knowledge while providing Amanda with a well-rounded understanding of her students’ abilities.

An example of meaningful assessment from Michelle’s classroom was part of a six-week literacy unit on folktales. Students learned about the different elements of folktales, explored several versions of The Three Little Pigs, and used a graphic organizer to compare and contrast the different versions. Students then created their own version of The Three Little Pigs. They were writing creatively and demonstrating their understanding of the unit content without using a fill-in-the-bubble assessment. As Michelle notes: “I don’t need a colored bar graph to help me determine how well my students performed on the assessment. I can have a conversation with anyone at any time about how my students are progressing, as well as the areas in which they need more support.”

No More Bubbling!

In an act of collective resistance, several teachers, including Amanda and Michelle, did not fill in the bubble sheets. Instead, they used the time to plan engaging and interactive lessons for their students, and meaningful assessments. School leadership did not receive this show of professional activism favorably. The teachers persisted in delaying compliance even when told by the principal that they would be reported to district headquarters.

When Michelle and Amanda were reported to the district, they initiated a meeting with the superintendent. During the meeting, he was unable to articulate the purpose of the assessment and could not tell the teachers how it would be used. The teachers were given an extension to submit their “data” while the superintendent looked into their request. After the meeting, both teachers received letters from the superintendent citing that they had “failed to administer the test to your students . . . and if it is not administered your conduct will be in violation of the district’s job description; the district’s Employee Handbook Standards of Conduct; and the New Mexico Public Education Department Code of Ethical Responsibility of the Education Profession, and you may be subject to disciplinary action.” To this day, the district has not provided them with an answer as to how the assessments are used.

Transparency with Students and Families

The corporate education agenda is shrouded in powerful slogans and convincing rhetoric. Many families accept policies, particularly related to testing, as neutral or beneficial without realizing the ways in which corporations benefit from the never-ending cycle of testing. To make matters worse, many teachers are bullied into not speaking to families about these policies.

Shortly after the school received its F rating, Amanda organized a research unit on school grading. Concerned about the extent to which her students had internalized the F grade, Amanda decided to have the students create a newspaper with the school grade as the theme. Rebecca, Kersti, and I were invited to come to her classroom as volunteers to help the children with the different phases of research. The children interviewed teachers and administrators, assessed the school facility, and spoke with other students about the positive and negative aspects of their school. The children then wrote articles and published them as a newspaper that they disseminated throughout the school community. It included headlines like “Standardized Tests and Students” and “F Is for Fantastic.”

Through their research, the children were able to report that the school grade assigned to them by the PED did not accurately reflect the rigorous instruction and caring community that characterizes High Desert. One of Amanda’s 4th-grade students, Ian Campen, summarized what he and many of the students learned in a comic strip (see p. 25). In addition, both Michelle and Amanda provided families with information about the process of opting their children out of state and district testing. This included clarifying parental rights and dispelling misinformation about how parents’ decision to opt out might negatively impact individual teachers or the school as a whole. Michelle explained: “I told parents to do what is best for their child and not to worry about our school grade or what negative impact it could have on me. I’m not going to misinform parents or stay silent because I might get a bad evaluation.”

Amanda provided families with information about the amount of class time spent on testing, directed parents to links for opt-out forms and, like Michelle, encouraged them to make a decision based on the best interest of their child.

This commitment to openly discussing the possibility of opting out pushed Michelle and Amanda into unsettling territory. District policy requires teachers to sign test security documents promising not to disparage PARCC testing. Educational scholar Diane Ravitch has likened such oaths to McCarthy-era loyalty oaths.

Michelle and Amanda posted their “minimally effective” end-of-year evaluations outside their classroom doors, confronting the ways that evaluations are used as a shaming mechanism to promote compliance. Both teachers also sent their evaluations home with students as part of their final classroom newsletters, alongside the rich commentary of their students highlighting what they had learned and what they would miss about their classrooms. Many parents wrote the teachers supportive notes, expressing outrage at the negative evaluations and committing to speaking out about the fallacies inherent in the evaluation system. Both teachers read their evaluations to the board during a public forum. Michelle shared the “evidence” that she had received for the low score her principal gave her (2 out of 5 points) in Domain 4—Professionalism:

She very vocally disagrees with anything involving testing and assessment, which she believes is in excess. The instructional coach reports that she is argumentative in data meetings because she is in opposition to what is being required of her. Ms. Perez is respected by her colleagues. She has been very active in criticizing [the district] and their requirements this year, which in turn has created turmoil in the building. She has had difficulty adapting to the use of Stepping Stones [the district’s newly adopted math curriculum, distributed to teachers the week before school started] and its assessments.

In most settings being respected by one’s colleagues is a positive indicator; in this instance, the respect that Michelle garners was considered subversive and threatening to a culture of compliance. The school board deflected responsibility to the PED, indicating that their hands are tied when it comes to testing. But ongoing testimony at school board meetings by many teachers has pushed the board to begin to take a stand against other corporate initiatives. For example, after consistent pressure from teachers and community members, the board recently rejected a proposal supported by the PED and sponsored by, among others, the University of Virginia Darden School of Business to “turn-around” five schools in the district.

Protest as Professionalism

The burning of evaluations was not the first collective protest last year. Teachers, parents, university faculty, and community members participated in countless instances of shared protest. For example, during PARCC testing, protesters gathered each morning before the start of the school contract day to raise awareness about PARCC testing and corporate school reform. As families approached the school to drop off their children, the protesters had an opportunity to talk with them about the problems with PARCC. In addition to raising community awareness about standardized testing, for teachers those discussions alleviated some of the stress associated with having to administer a test that violated their professional ethics. The protests lasted for the duration of the testing window, almost 40 days.

One thing that has become clear from our collaboration is that teachers and teacher educators need to rely on each other to foster professionalism as activism in our respective settings. Cultivating a socially just and equitable society is as much about our interactions as it is about our actions. By showing up in solidarity and building bridges between schools and universities we aim to nurture the potential of our students, their families, our schools, and our democracy.