Stanford/Pearson Test for New Teachers Draws Fire

The fight for—and against—standardized testing is heating up in teacher credential programs. It has burst into flames at the University of Massachusetts.

Back in 2010, Rethinking Schools published an article by teacher educator Ann Berlak on PACT (Performance Assessment for California Teachers), a high-stakes, standardized test for teacher credential candidates. Berlak wrote the article, ominously titled “Coming Soon to Your Favorite Credential Program: National Exit Exams”, “in the hope that the rest of the nation might learn from and not replicate our experience.”

By June, the national version of PACT, relabeled TPA (Teacher Performance Assessment) and then edTPA, had been field tested at 160 colleges and universities in 22 states, several of which have accelerated the adoption of the edTPA for licensure. EdTPA is a joint venture of Stanford University and Pearson, now the largest assessment company in the United States. To pass the edTPA, credential candidates submit a classroom teaching video and 40-50 pages of written responses to canned “reflective questions”; these are scored by contract employees “calibrated” by Pearson to review the assessments for $75 apiece, according to their website.

At the University of Massachusetts Amherst, the field tests didn’t go as the university and Pearson expected. Barbara Madeloni, coordinator of the Secondary Teacher Education Program, had worked with the TPA for two years, and explained to us she had “substantial concerns about it as an assessment instrument.” The essay portion “not only leads students to answer only the specific questions determined by external forces to be relevant to their student teaching experience, but narrows the possible ‘good’ answers through the limitations of a rubric. In a high-stakes environment, where the score on this ‘assessment’ determines a student’s ability to graduate and/or receive a teaching license, the production of the right answer dominates the experience.”

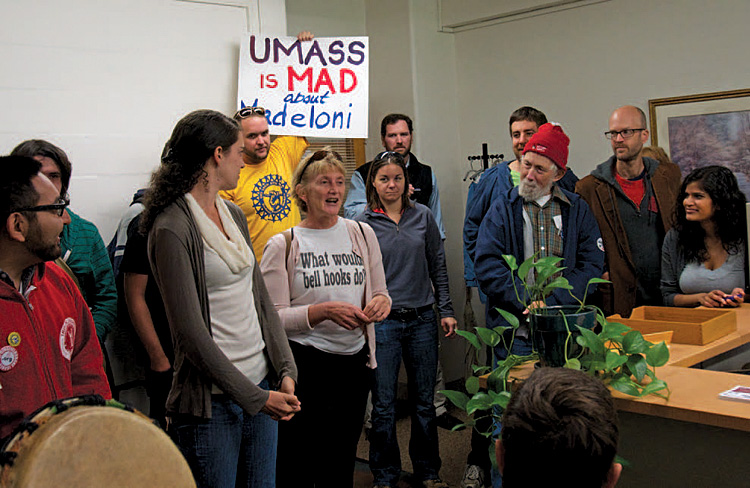

She and her colleagues tried to discuss the issue with administrators, without success. So she opened up the discussion in her student teaching seminar. Students wanted to be evaluated holistically by teaching faculty who knew them; they objected to being guinea pigs for Pearson. Citing ethical standards for research studies, the students demanded they be given informed consent about the pilot study, its purposes, and the security and confidentiality of their work. After three months of insisting first that informed consent wasn’t necessary, and then that it was implied by uploading the required program, UMass finally agreed that students had a right to opt out of Pearson’s field test. When given the opportunity, 67 of the 68 secondary education student teachers opted out.

Education Radio produced and aired a program about the students’ resistance. “Energized by the students’ success, anxious to share their story for others to be inspired by, and certain that there were more voices to be heard speaking back to Pearson,” Madeloni contacted Michael Winerip at the New York Times. He wrote a story on the UMass controversy, quoting Madeloni and some of her students. Winerip’s story appeared May 6, 2012; 17 days later, Madeloni received a letter of nonrenewal of her contract.

“The expectation was that fear would silence us,” Madeloni says. “As a teacher educator in a licensing program, I am both surveilled and surveillant. My job involves reviewing assessment data, assuring that others complete various protocols and audits. I felt implicated, and the shame of this self-awareness invited me to silence myself, to bury my head and just go within the system. . . . My choice to speak out came down to this: If I find myself thinking I live in a world where it is too dangerous to speak out, that is when I absolutely must speak out.”

Can’t Be Neutral

In response to the attack on Madeloni, students, faculty, teachers, and parents formed Can’t Be Neutral (cantbeneutral.org), a social justice education activist group. Their demands include Madeloni’s reinstatement, transparency in the university’s relationship with Pearson and other for-profit education companies, and that the School of Education embody its stated commitment to social justice. As the group explains at its website:

We here at Can’t Be Neutral understand that what happened to Barbara can happen to any of us. We understand that the public good, and public education in particular, is under attack by forces looking to exploit education for profit, to privatize and commodify all public spaces. We understand that the incursion of the for-profit company Pearson into teacher education through the TPA is one more example of this attack. . . . We are disturbed by both the willingness of the School of Education to collaborate with these privatizing and dehumanizing forces and their silencing of voices of critique and opposition.

Can’t Be Neutral has organized letters in support of Madeloni and more than 2,000 petition signatures nationally and internationally. They held a teach-in, “Education for Democracy, Not Corporatocracy,” where students, faculty, teachers, parents, and community members attended a day of events that included a panel of students who resisted the Pearson field study, and workshops led by scholars David Stovall, Celia Oyler, Jesse Turner, Janaki Natarajan, Sangeeta Kamat, and Peter Taubman. They are joining United Opt Out to “Occupy the DOE” in April; participating in a conference sponsored in part by the City University of New York Professional Staff Congress (the union that represents faculty and staff), “Reclaiming the Conversation,” in May; and continuing to pressure the university to reinstate Madeloni.

High-stakes testing and academic freedom are obviously issues here. Another issue is the role of Pearson and other for-profit education corporations. “There is concern,” says Madeloni, “over the link between Pearson curriculum development for the Common Core standards that are being adopted as part of Race to the Top by many states, the requirement for students to show evidence of teaching to these same standards within the TPA, and the expected new revenue for Pearson from the testing that will result from implementation of Common Core standards. I stand, in the face of these connections, aghast. How do we come to accept the propriety of this money grab?”

As the battle against edTPA has gained ground, the university has been forced to step back. Christine McCormick, dean of the UMass School of Education, told Winerip in an email that edTPA is not being used this school year at UMass. According to Winerip, “she said the department is now preparing a research paper that will explore all different kinds of teacher assessments—including assessments that don’t primarily rely on testing.” (New York Times, Oct. 1, 2012).

The fight is far from over. As Madeloni told Art Keene in an interview for a UMass faculty newsletter, “This is eerily similar to what is happening in K-12 education, where teachers’ voices are silenced, and teaching is subject to technocratic high surveillance accountability measures that destroy the potential of the classroom to be a place of inquiry, creativity, and liberation. . . . It is my responsibility as a teacher educator to not only help students see and understand what is happening in and to schools, but to support the development of the strength, wisdom, and courage to determine how to intersect with that system in order to change it.”