Action Education: On The Front Line in Minnesota’s Social Studies War

In early September 2003, the Minnesota Department of Education released a first draft of new K-12 social studies standards for public comment.

As a parent and former social studies teacher, I struggled with disbelief and anger as I forged through the 56-page document. It was packed with 233 standards and 848 corresponding benchmarks specifying what students might have to know about U.S. history, world history, geography, economics, and civics. I felt that my own children’s and their peers’ futures would be at risk if they were forced to passively learn the standards’ factoids. (Click here for examples from the initial standards document.) I knew I needed to get involved, but I didn’t know how.

The Resistance Begins

Two days before the first and only public hearing in Minneapolis-St. Paul, I shared my frustrations with a former colleague. She reminded me that effective social action requires a collective voice. We hatched the idea of starting an online petition calling on local school boards, the state legislature, and the governor to reject the proposed standards.

The next day at a Sunday dinner I asked five adult members of my family to take a look at the standards and let me know what they thought. Their initial negative reactions to the document gave me confidence that a petition would resonate with a wide group of Minnesotans. That evening we formed Minnesotans Against Proposed Social Studies Standards (MAPSSS). We immediately started developing a handout, a website, and an online petition listing our major concerns.

We created MAPSSS because we were concerned about what and whose knowledge was included, omitted, and distorted in the proposed standards. We were also disturbed by the flawed process used to develop the standards. Our objections included the following:

- An overemphasis on rote memorization of trivial and irrelevant factoids instead of critical thinking.

- Too numerous, repetitive, age-inappropriate, and costly.

- Conservative ideological and political bias throughout.

- Narrow and distorted coverage of diverse groups and world regions while emphasizing white, male, U.S., and Eurocentric perspectives, accomplishments, events, periods, people, and places.

- A rushed timeline that included just five meetings in August to develop the draft, two months for public comment, and one month to make revisions without further public input.

These objections ended up resonating with critiques hundreds of people raised at public hearings and on the Department of Education website.

Before long, we learned why the content of the standards was so problematic. Minnesota Commissioner of Education Cheri Pierson Yecke had stacked her 44-member committee with conservative parents, businesspersons, school board members, professors, and K-12 educators. Many were advocates of E.D. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge curriculum, and several members were involved in home schooling and private schools not accountable to the standards they were creating. The committee was also overwhelmingly white and suburban. This process marginalized public school educators, parents, and especially people of color.

Resistance Movement Grows

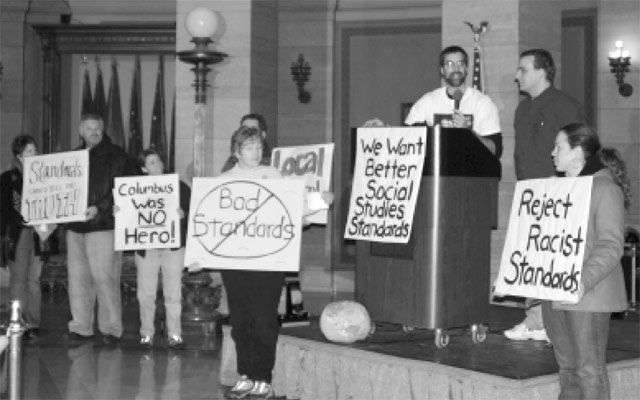

Nearly 300 people attended a St. Paul hearing in late September where teachers, parents, and students spoke eloquently against the draft standards. Headlines the next day in both major newspapers read, “Proposed standards draw fire” and “Proposed school standards face critical reception.”

Over the next month, an opposition network of people well beyond MAPSSS began to form as the public continued to speak out against the proposed standards. Dana Carmichael-Tanaka was the social studies specialist at the time for Minneapolis Public Schools, the state’s largest and most diverse district. She and Jennifer Bloom from the Center for Com-munity Legal Education mobilized more than 100 social studies teachers and professors throughout the state. Leaders of the Minnesota PTA, Parents United for Public Schools, and Save Our Schools helped round out a resistance that included people of all political stripes.

Students also spoke out against the proposed standards. At one of the final hearings, students from an anti-racist program called Freedom School challenged Commissioner Yecke. They said they could not see themselves in the standards or on her appointed committee. When a student pressed Yecke to disclose the racial makeup of the committee, she replied,” I don’t know. I don’t pay attention to those things.”

As public expression of dissatisfaction over the standards continued to grow, media coverage also grew. At the end of October, MAPSSS delivered our petition to the Governor’s office on behalf of 1,430 Minnesotans. The next day, four public school teachers on the standards committee released a “minority report” expressing serious concerns about the commissioner’s process and the standards. On November 1, the morning in which the standards committee was scheduled to meet and revise the standards, several parent-led groups held a press conference demanding accountability to public feedback.

After the teachers’ press conference, when the spokesman for the Department of Education was asked why social studies standards had become so controversial in Minnesota, he said, “The culture wars have come to Minnesota.” Four days later he was scrambling to do damage control after Minnesota Public Radio broadcast Commissioner Yecke saying that children should not be taught Native-American views of Columbus because he was not responsible for the genocide of indigenous peoples. Native-American leaders organized a protest rally at Department of Education headquarters demanding an apology and calling for Yecke’s resignation. She refused to apologize or resign, and her standards writing committee seemed to ignore the controversy. The final draft standards still listed Columbus as a famous person whose holiday was to be celebrated.

Yecke released the final draft standards to the public in mid-December, calling them “phenomenal.” She told the press she believed the document would satisfy criticisms raised in the hearing process.

Lobbying and Compromise

In March, Minnesota’s Republican-majority House voted to support the increasingly embattled commissioner by approving the proposed standards. The Senate, with its Democratic majority, rejected the proposed standards. But they passed an alternative set of standards, which were developed by social studies teachers and historians. Many of us found the alternative standards flawed but more politically balanced, less Eurocentric, and more age-appropriate than the ones Yecke’s committee developed.

In the last week of the session, House and Senate leaders had secretly agreed to have a bipartisan appointed group of educators work around the clock with staffers at the Department of Education to try and develop a compromise set of standards.

On May 16 at 3:30 a.m., with three hours left before the sun would rise and the legislative session would end, I watched Minnesota’s elected officials pass this compromise set of standards without debate. Just a few minutes later, the Senate finally took action on the issue of whether or not to confirm Commissioner Yecke. Senate Democrats showed rare unity in unanimously rejecting her appointment.

So, with the passing of an improved, yet still-imperfect set of standards into Minnesota law, MAPSSS became extinct. Yet, many of us have stayed connected through an electronic newsgroup so we can collectively monitor and respond to the ongoing assault on public education. Two new advocacy groups have formed: Minnesotans for Better Education, Standards, and Testing (MinnBEST) and Citizens for Learning, Achievement, and Successful Schools (CLASS). They created a new online petition to restore state education funding and ensure that students have adequate opportunities to reach new state standards.

Lessons and Dilemmas

I learned a lot in the process of organizing against the standards. Within weeks of creating MAPSSS, I learned to stop trying to control the movement and to instead nurture decentralizing it. Dana, Jennifer, and I hosted a meeting in Novem-ber where more people assumed responsibilities. One teacher created a Yahoo email newsgroup to provide our network of people with a means to share news from the struggle against the standards and bounce ideas off each other. This listserv became one of our most important tools because it created a sense of community among people who, for the most part, had never met each other, and it allowed for daily communications at times that were convenient to each individual.

We also quickly learned that the coalition of individuals and groups opposed to the standards was too politically diverse to unite under one line of critique. We were Democrats, Republicans, and independents with different perspectives. Some of us lived in cities, others in suburban or rural areas. So, rather than taking either a radical (i.e., “the standards are racist”) or mainstream (i.e., “the standards are too costly”) approach, we encouraged a continuum of resistance from a variety of sources.

Finally, we wondered if drafting alternative standards would make us part of the problem or part of the solution. As a sign of how much our society has come to accept the notion of “standards” over the past 15 years, it was clear that a position against standards of any sort would not have resonated with elected officials and their constituents. We constantly heard people ask us, “Are you against standards for students and teachers?”

This reality reflected a serious dilemma. From one angle, drafting alternative standards could be a way to improve the standards and provide a voice to those who were marginalized. And if there were no state standards for social studies but there were standards (and assessments as required under NCLB) for language arts, math, and science, social studies could get marginalized in the broader school curriculum. Yet, if we helped develop alternative standards, it was not clear who would draft and review them and how this could happen in the short time available.

In the end, MAPSSS publicly opposed the development of alternative standards because we were highly critical of the rushed and non-inclusive process used to develop the commissioner’s standards. However, several teachers and professors who had signed the MAPSSS petition and were a key part of the resistance movement volunteered to draft the alternative set of standards for the Senate.

Yet I am disappointed that we did not more aggressively question the whole issue of whether there should be highly specific social studies standards at all. I think that having social studies standards helps bolster a neo-conservative education agenda that rests on standards and testing regimes and undermines public education. Now K-12 teachers and their students will be pressured to “cover” some 77 pages of standards, compared to 23 pages of science standards, 38 pages of math standards, and 54 pages of language arts standards.

Throughout the standards battle we became acutely aware of how our struggle over state social studies standards was part of a much larger culture war going on in the country. When conservative think tanks such as the Fordham Founda-tion and ideologues such as Chester Finn, John Fonte, and Diane Ravitch weighed in on our local control issue in a presidential battleground state, they gave us motivation to persist.

Hopefully those of us who came together to fight the social studies standards will join with others to continue to raise our concerns about the direction of education in Minnesota and the United States. By raising our voices and organizing, we can provide a counterforce to those who would continue to standardize and privatize our public schools.