Abbott Elementary: A Sitcom with a Conscience

What starts off as yelling and sighing over the innocent farce of a ruined school classroom rug quickly highlights more systemic issues. There’s urine on it because the toilets don’t work. The teacher can’t lay out any more of her own money to replace it. The school’s administration doesn’t view it as important enough for a budget line item. And the child who would sleep on it during lunch when he couldn’t sleep at home suddenly has lost not just a path to engagement in class, but a safe haven.

So goes another day at Willard R. Abbott Elementary School, whose successes and tribulations are universal even if the building itself doesn’t exist beyond the Hollywood soundstages of Abbott Elementary — a TV sitcom told from the point of view of public school teachers and staff. It has closed its first season on ABC and was renewed for a second.

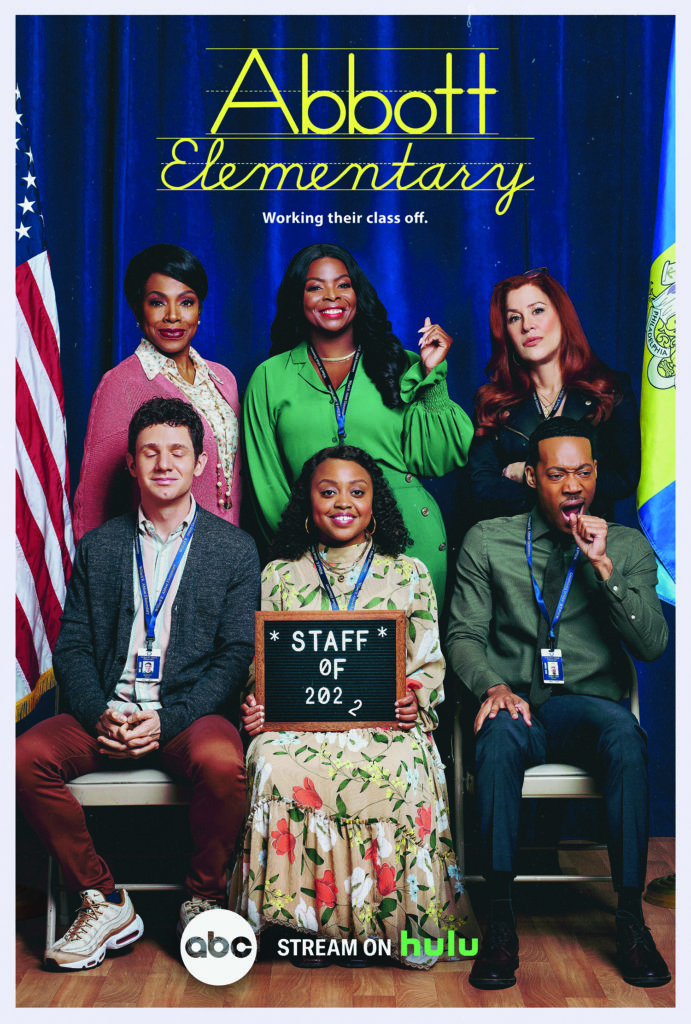

Philadelphia comedian Quinta Brunson parlayed years of work in online content, dramatic and sketch comedy series, and voice parts for animation into developing the show’s pilot. Inspired by her own education in the city and her mother’s work as a teacher here, Abbott stars Brunson as Janine Teagues, navigating her second year as a 2nd-grade teacher at the fictional school. Its episodes survey her colleagues, students, and interactions there through a comic and occasionally tragicomic lens as if followed by a documentary film crew, including interview segments, narration over A- and B-roll footage, and plenty of fourth wall-breaking looks of confusion and glee. It has abruptly and smartly buttressed the nation’s ongoing conversation — not to mention entertainment canon — about defending public education.

Prior to Abbott, this mockumentary format was most notably employed on The Office, a sitcom with more than two decades in the public consciousness. And much like The Office, Abbott Elementary has a core ensemble cast that evokes strong responses. Brunson writes foils for her Ms. Teagues character that would be caricatures were it not for every joke having a grain of truth at its center. She is joined by Janelle James’ scheming, failing-upward principal Ava Coleman (the school’s version of Dunder Mifflin’s Michael Scott); Sheryl Lee Ralph’s firm and competent kindergarten teacher Barbara Howard; Lisa Ann Walter as South Philly-proud Melissa Schemmenti; and Chris Perfetti playing Jacob Hill, history teacher and would-be white savior.

The most complex of Brunson’s creations might be Gregory Eddie, a powder keg of educational concerns played by Tyler James Williams. His arrival is a result of training and retention issues that see a frustrated staff member leave midday, never to return. He represents a portmanteau of two common forms of teacher churn: the long-term substitute and the teacher fast-tracking their classroom experience in order to become a principal. He also becomes the apex of a workplace romantic triangle, fending off Coleman’s harassment while quietly falling for Teagues. With Mr. Eddie set upon by new conflicts and critiques from all sides, Williams has perfected a “please help me” look into the mockumentarians’ lenses.

The show’s strength lies not just in the content of its characters, but the character of its content. The realities of public education, and in particular its treatment of BIPOC students, staff, and communities, stand center stage. They inform the battles that Teagues wants to fight and believes can be won. “I don’t want to wait for someone to get to it,” she says in the midst of a battle to replace a light bulb. “You know, our children have needs that deserve to be met. And I’m going to fix this. Nothing is going to get in my way.” They also inform the laughable results of such battles: the slapstick of Teagues stuck on a ladder trying to fix that light, all-too-real jokes like a class being left in the care of the building’s custodian, even plausible absurdities like standardized test data being funneled to the prison industrial complex.

These comprise the kind of coping mechanism humor found in exhaustion and endless disappointment, and they also indicate where the show’s parallels to The Office end: If you couldn’t laugh with Abbott Elementary, you’d cry. Brunson’s world is by turns sweet, silly, sad, exuberant, and mad as hell.

For one thing, Abbott Elementary recognizes the magnification of trauma through simple misallocation of resources; “I’d say the main problem in the school district is, yeah, no money,” Teagues laments early on. “The city says there isn’t any, but they’re doing a multimillion-dollar renovation to the Eagles’ stadium down the street from here.” We see how much effort goes into bringing the smallest light of joy to the darkness, as teachers try to connect with students through dance, roasting, Philly slang, and collective bargaining. The show also explores unintended consequences of good intentions, such as the cafeteria manager rebuffing Ms. Howard and Mr. Hill’s efforts to feed students from a school garden.

And woven through it all is Principal Coleman’s misbehavior — it offers priceless moments of comic relief but also reinforces the idea that teachers often run the school in spite of management, not alongside it. In one episode, she authoritatively tells a student in her office she’s the principal only to have him respond, “But you don’t do anything.” This brief exchange is both hilarious and a withering critique of a school system that often prioritizes administrator positions over classroom aides and teachers. Absent the canned reactions or live audiences of your typical studio-set sitcom, Abbott punchlines and observations like these hang in the air for potentially uncomfortable processing.

To that end, the show must wrestle with some Hollywoodized constructs as it moves forward. In particular, it draws many lines between less and more experienced staff in order to generate teachable moments. These often resolve to happy endings of mentorship and understanding, but it seems unrealistic to see something like Schemmenti dumping a troublemaking 2nd-grader on Teagues — and subsequently refusing to help, in order to humble the newer teacher — leading to anything but resentment between actual educators, rather than a shared realization that the student needed not punishment but more challenging 3rd-grade work. And without references to the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers or instances of mass action by the adult cast, so far Brunson’s portrayal of unions rests on one bit player’s woefully outdated stereotype of the trade unionist as Italian mobster.

Still, as good comedies should do, we note main characters’ capacity for emotional growth, personal change, and exceeding expectations. Across individual episodes or, maybe more importantly, incremental arcs across a season, Abbott Elementary cues us to the small successes uncovered by those called to teach: the reason to believe, the reason to stay, finding that “teacher voice.” The show also reminds us that regardless of parental, administrative, and legislative warnings against bringing politics into classrooms, teaching remains a political act. That is to say, the political becomes personal for the Abbott staff as it does for educators in the real world. Decisions far beyond the school door greatly affect what can happen when it closes and the bell rings. And laughs are always a possible byproduct of the stress of working to change and save lives, of relentlessly trying to do the right thing.

Want more content like this? Subscribe now to Rethinking Schools! A one-year subscription is just $24.95 and helps support our efforts to provide antiracist and social justice curriculum and articles for educators everywhere.