Preview of Article:

A Social Justice Data Fair

Questioning the world through math

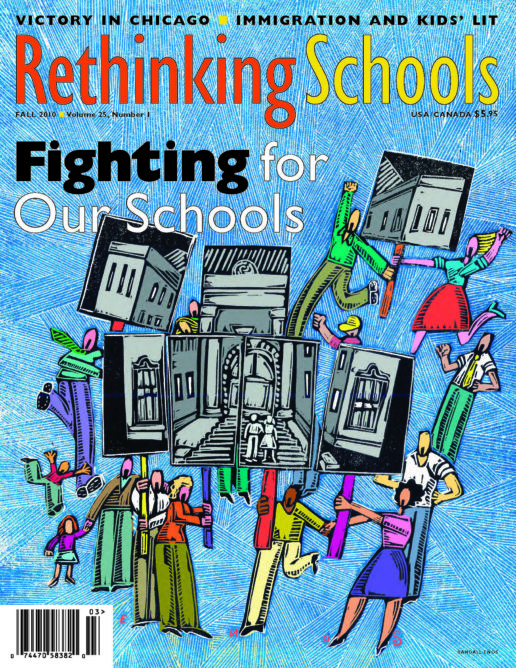

Illustrator: David McLimans

The gym roars with 50 different conversations. Around the walls, and throughout the room, students stand before their projects. Most are pasted on poster board, others on reused pizza boxes. Over the din, the girls describe their work to fellow students, teachers, and a handful of “willing listeners”—volunteer adults (parents, mostly) who have come to find out what the kids have learned.

Along the back wall, the 5th- and 6th-grade classes present their findings from the school waste audit. The 1st- and 2nd-grade students have studied how hard it is to live on the “welfare diet”—the contents of the average food bank recipient’s weekly allotment—and have created graphs to show what they, and their families, have eaten that week. The older girls have prepared individual projects. Melanie, 7th grade, wondered if children with autism received the same amount of funding as children with other disorders, and her results are strikingly demonstrated on a bar graph. Mi-sun, 9th grade, used a line graph to demonstrate that Korean students, among all nationalities, are most likely to commit suicide. Andrea, 7th grade, used a scatter plot to investigate the correlation between GDP and carbon dioxide emissions. On a table, the results of the 6th-grade class’s collective research is illustrated, with labeled bags of rice offering a three-dimensional representation of what the world eats every day: China has a huge pile; Iceland just a few grains.

The lights flicker on and off, and the conversations die down. “We’re halfway finished,” Michelle calls out. “It’s time to switch! Those of you who were presenting should now listen, and those who were listening should now present!” The noise picks up again.

The Social Justice Data Fair has been held at the Linden School in Toronto for the past several years. It is an opportunity for our math students to use data management skills to study issues they’re concerned about. The fair is an example of how our independent, girl-centered school for students in grades 1 to 12 tries to include topics of social justice in our curriculum. Compared with other Toronto-area private schools, our school is quite culturally diverse, and we enroll students from many nontraditional families. Most of our families support learning math through the lens of social justice. (Parents have commented how much they enjoy having their daughters bring math class conversations to the dinner table.)