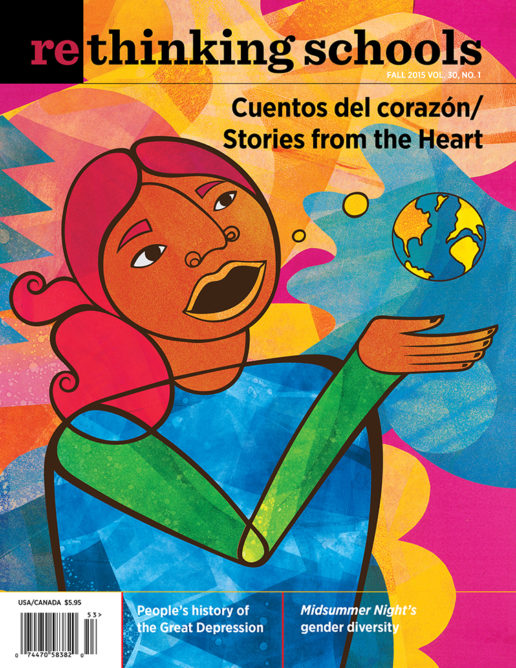

Preview of Article:

A Midsummer Night’s Gender Diversity

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

We’d diagrammed the love quadrangle. We’d laughed at Bottom’s word choices. We’d recited Titania’s speeches. We’d played games to help us understand Shakespeare-speak and subtext, and we’d written lines with scansion marks to see the rhythms. We’d acted out Puck’s tricks and reviewed Shakespeare’s colorful insults, and it seemed like the class was having a grand old time. Then David approached me after class.

“Ms. Porosoff, are we going to do anything with this book? You know, besides read it out loud and have you translate it for us?”

Stab. I knew just what he meant: Instead of the deep dig into a text’s ethical and societal questions that I usually bring to my English class, we were acting out a shallow story about lovers, fairies, and donkey-headed bad actors, with some iambic pentameter thrown in. As defensive as I felt (“But it’s Shakespeare!”), I knew David was right. I wanted to meet his challenge—to approach A Midsummer Night’s Dream more critically and in a way that felt more relevant to the students’ lives.

As if Puck himself had magically contrived it, that same week I attended a workshop where Jennifer Bryan presented her New Diagram of Sex and Gender (See References), which offers a way to think beyond binaries by using a set of continuums for biological sex, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation. At the workshop, I came up with a new way to approach A Midsummer Night’s Dream with my 7th graders at Ethical Culture Fieldston, a private pre-K-12 school in New York (about 35 percent of the 1,700 students identify as students of color, and 22 percent receive financial aid).

Three Adjectives

For the first day of the lesson, I broke the students into four groups and assigned each group a set of characters: the lovers (Hermia, Helena, Demetrius, and Lysander), the Athenians at court (Egeus, Theseus, and Hippolyta), the mechanicals (Bottom, Quince, and Flute), and the fairies (Oberon, Titania, and Puck). Working together, the students in each group had to agree on three adjectives that defined each of their characters. The students described Helena, who rats out her best friend in an attempt to get attention and later gets her man through fairy magic, as desperate, jealous, and self-conscious. Her beloved Demetrius, who went after Hermia even though she was in love with someone else, was stuck up, narrow-minded, and persistent.

Next, the student groups switched character lists and had to revise the adjectives, keeping at least one and changing at least one adjective per character. I wanted them to negotiate meaning and return to the text for evidence to support their claims about their characters. So even though proud, beautiful, and seductive all seemed fitting descriptors for Titania, the group that was working on her cut proud (they reasoned: “Just because Oberon called her proud doesn’t mean she was!”) in favor of independent-minded (citing how she refuses to spend time with Oberon or give him the changeling boy). I pushed that group, asking them how they knew Titania was beautiful when there’s no description of what she looks like. Caroline said, “She’s the fairy queen.”

The next day, I told the class that we’d be discussing a theme that interested Shakespeare: gender. I showed them Bryan’s diagram and went over the concepts of biological sex characteristics, gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation—and how these don’t necessarily “line up”; a heterosexual woman can have very masculine characteristics, and a person can be born with XY chromosomes but present as a girl. (The students had studied genetics in their life sciences class, so they knew what XX and XY meant. Still, they were surprised to learn that XX doesn’t equal girl.)

I asked the students what messages they get about how girls and boys are “supposed to” look and act, and what happens when people challenge those assumptions. Some students tentatively mentioned labels for those who defy gender expectations—tomboy, metrosexual, and homo—and for relationships that fall outside societal comfort levels—bromance, manny, and girl-crush.

“But a bromance doesn’t mean you’re gay,” Nick protested. “It’s the opposite.”

“Right,” Caroline said, “But why do you need a label at all? There’s no term like that for girls.”

“Because it’s different for girls.”

“Why? Girls are allowed to spend a lot of time with their best friends, but guys aren’t?”

“Guys are, too. It’s not like if I hang out with another guy all the time, everyone starts saying we’re gay.”

“I don’t think when people call it a bromance anyone thinks the two guys are actually gay. It’s as if you’re making fun of the idea of guys spending so much time together.”

I jumped in: “Caroline, it sounds like you’re saying that the word ‘bromance’ reveals a cultural conflict between gender identity and gender expression. In what we call a bromance, two guys are very close friends.”

“But having close friends isn’t gay,” Nick said.

“But is it considered feminine? I think what we’re getting into is how gender identity, gender expression, and sexual orientation all get lumped together. Why is a very close friendship between two straight, masculine guys a problem?”

“It’s not a problem.”

“Then why do we label it a bromance?”

Class was over. I left them with the question.