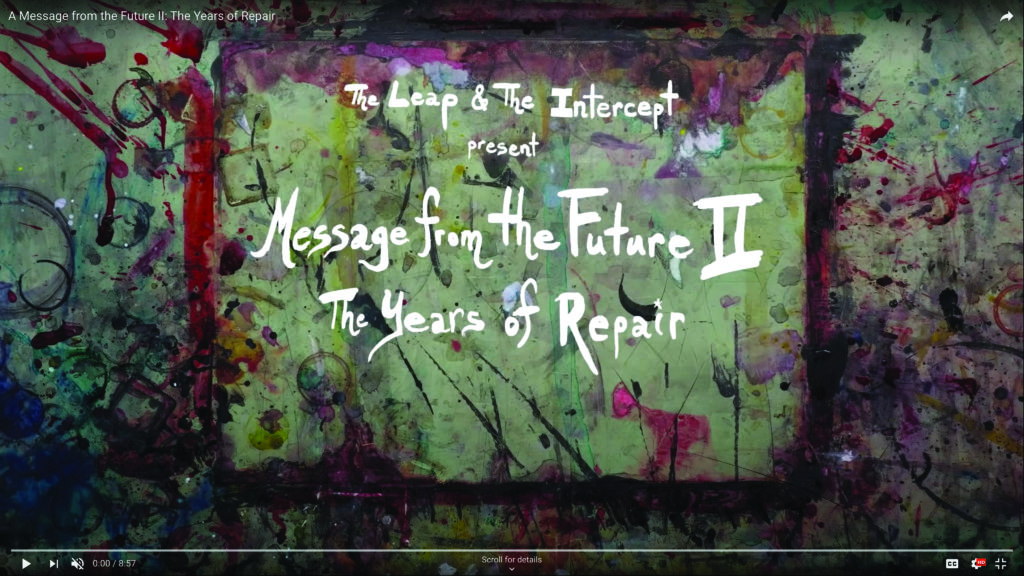

A Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair

Let’s Not Ask Our Students to “Return to Normal”

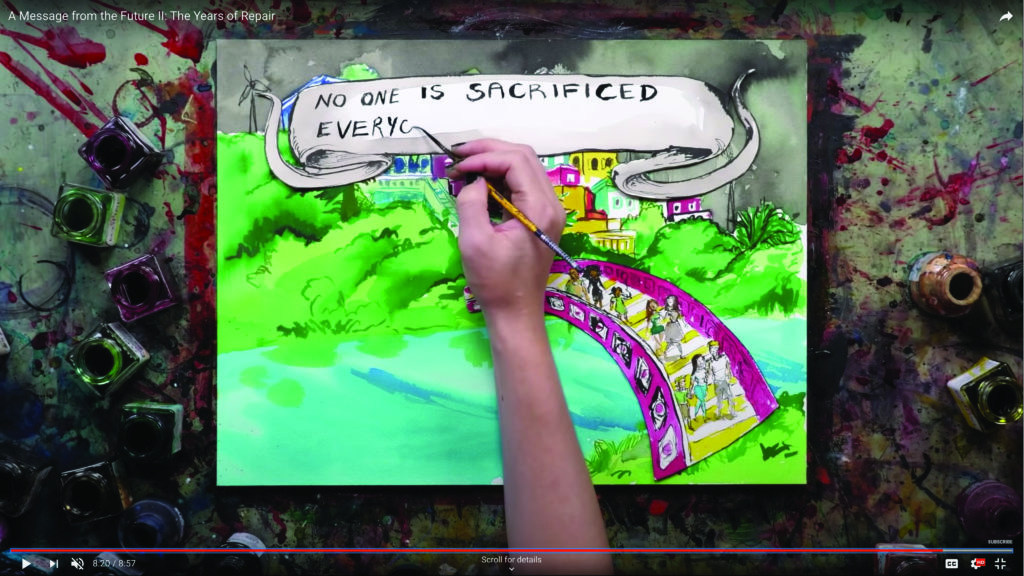

Illustrator: Molly Crabapple

What are the lessons of the pandemic? In this time of interlocking crises, what aspects of our world are most in need of repair? These are questions I plan to ask more frequently and more urgently as a teacher, especially as we move toward the promise of a COVID-19 vaccine, and the talk of a “return to normal.” One way I had a chance to do this recently with my students was by sharing the excellent short film A Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair, and asking students to reflect on the lessons for today offered by the film’s writers and producers: Naomi Klein, Avi Lewis, and Opal Tometi.

In the article that accompanies the film at the Intercept, Klein shares the questions that guided the film’s production: “Do we even have a right to be hopeful? With political and ecological fires raging all around, is it irresponsible to imagine a future world radically better than our own? A world without prisons? Of beautiful, green public housing? Of buried border walls? Of healed ecosystems? A world where governments fear the people instead of the other way around?” The product of these questions is a complex, sometimes dark, but ultimately hopeful story told in the eight-and-a-half-minute film, set to the same style of stunning watercolors by Molly Crabapple that helped make the original Message from the Future so beautiful and compelling.

I’ve used the first Message from the Future, narrated by New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, with high school students and adults, as I ask them to imagine an ecologically and socially just future worth fighting for — not the dystopian future that we are so often told to accept as inevitable. Similarly, our Portland Public Schools Climate Justice Committee recently used the first Message from the Future film at one of our meetings to help encourage participants’ radical imaginations as we envisioned what a Green New Deal for Schools might look like in Portland. The conversation that followed was inspired and utopian, in the best sense — unconstrained by the limited vision of what is possible within current school budgets starved by years of austerity. The power of both films lies with the underlying assumption that not only do we have a right to be hopeful, but indeed that fighting for a better world has to involve the sort of dreaming and visioning that can chart a path from here to there.

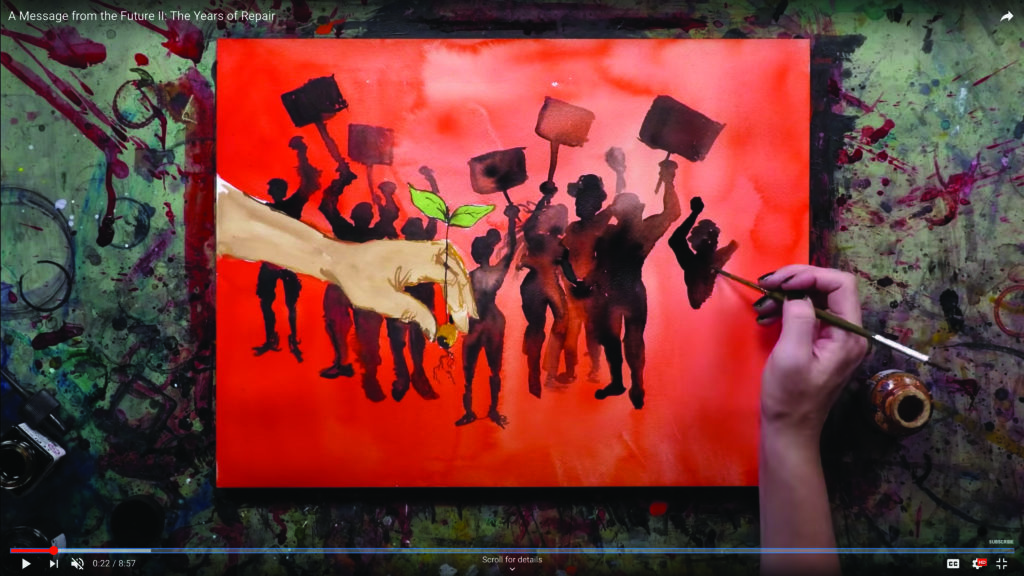

Where the first Message from the Future offers a decade-long vision of radical transformation, the result of Green New Deal policies passed by a progressive majority in Congress and the White House, the second film takes a more grassroots and more international approach to imagine the “years of repair” that could follow the coronavirus pandemic. The focus in The Years of Repair is less on the halls of power in government, and more on the power that grows from the streets and out of communities. Klein explains the intention of this shift: “This time, rank-and-file organizers and activists would be the stars. Given the array of corporate powers resisting change, and the bleak electoral options on offer, social movements are now the only force left with the power to grab the wheel of history and veer us off our current deadly trajectory.”

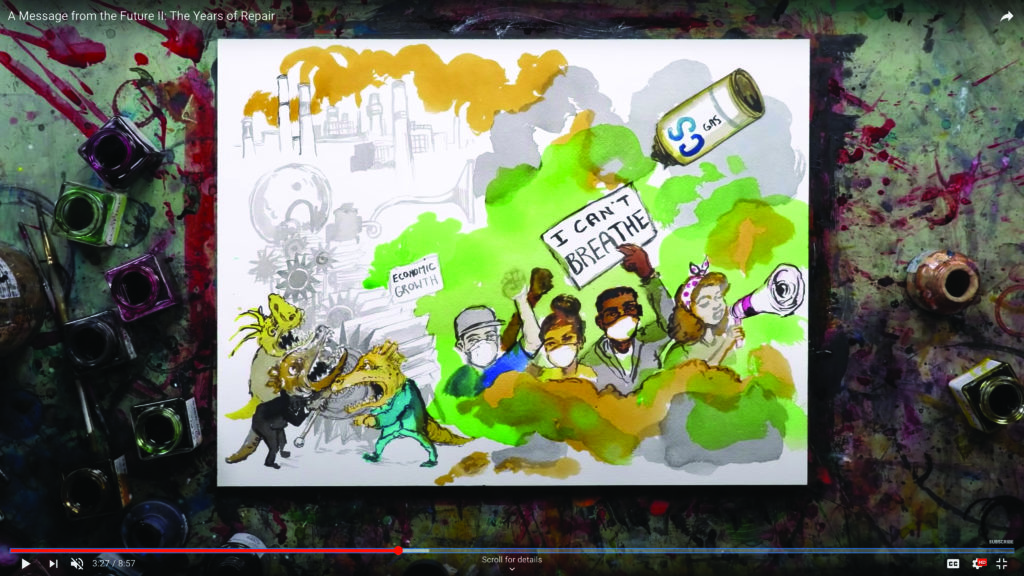

I’ve tried to make social movements and grassroots activism the central focus of my teaching about the climate crisis in recent years, to help students rethink the “benevolent leader” theory of change implicit in much of their social studies education, and to challenge the “power of the individual” narrative that pretends we can buy green and recycle our way out of the crisis. I appreciate that The Years of Repair helps students envision how movements for Black liberation, workers’ rights, immigrant justice, Indigenous rights, and environmental justice have interlocking roles to play in repairing our broken social and ecological relationships. As Molly Crabapple’s stunning paintings transition from Black Lives Matter protests to renters and workers striking in streets across the world, and from Indigenous Land Back campaigns to community farms designed around the needs of pollinators, we can’t help but see connections between all these issues and movements that are too often seen in isolation.

These connections were prominent in the reflections shared by my Environmental Justice students after we watched the film together, including a student who wrote that the film helped illustrate for her “how issues of colonialism, capitalism, and racism are all intertwined with the problem of climate change.” My students also shared an appreciation for the solemn focus in the film on the ways that some of the problems we currently face are likely to get worse, including climate-fueled disasters and a terrifying reference to future pandemics, such as “COVID-23.” Many students shared a sense that the film felt more somber than the first Message from the Future, but that this also made it feel “more honest and realistic,” as one student commented. Most surprising for me was the sentiment shared by several students that this realism helps to make the film more hopeful — that through its honest portrayal of the struggles and hard work of repair that lie ahead, it helps us to think seriously about the future at a time when it can be hard to imagine any sort of life beyond the pandemic.

Another aspect of the film that stood out to students is the intimate portrayal of humanity, a story told through images of hands, “the hands that packed the box, that picked the tomato, that planted the seed . . . the hands that stroked the brow, that said goodbye. The hands were us, all of us. That web of hand to hand, and breath to breath relationships was a reminder that we are entangled, making each other sick, keeping each other alive.” I appreciate this section for a couple reasons. One is the reminder of the radical interdependency that underlies all life on Earth, that we fail to recognize and honor at our peril — and that has been thrust back into our collective consciousness at moments throughout the pandemic. This section also helps explain why these interdependent relationships are easily forgotten in a class society — the exploitation of workers who face a disproportionate share of risk is so often hidden from view in the meatpacking plants, the agricultural fields, the package distribution centers, and other places of “essential” work that allow the privileged to “shelter in place,” at home. The film describes what it will take to repair and rebuild a society centered on just economic relationships: robust public investment in housing, health care, and education, the restoration of polluted landscapes and communities, and reparations for enslavement and genocide that continue to create increased vulnerability within Black and Indigenous communities. It concludes with the slogan “No One is Sacrificied. Everyone Is Essential.”

One of the ways I’m using The Years of Repair with my students is as an artistic model and a source of inspiration for them to create their own artistic renderings of a future worth fighting for. We’ll share the poems, narratives, comic strips, and paintings they have created in upcoming classes, and I look forward to continuing the work of radical imagination that began for us with The Message from the Future films. I’m also planning to have students research the coalition of groups — including the Movement for Black Lives, La Vía Campesina, Global Nurses United, and the Sunrise Movement, among others — that collaborated with the film’s writers and producers to help launch The Years of Repair and to use it as an organizing tool in their work. I’ve taught about many of these organizations in the past, but I’m grateful that, in this case, students will be able to see them as a coalition — a movement of movements — already demonstrating what it looks like to engage in the difficult and necessary work of repair.

As the vaccines roll out and we begin to imagine life after the pandemic, we can help our students question the call to “return to normal,” which not only disregards the sacrifice and death that have enabled companies to profit and stock markets to rise while millions face unemployment and eviction, but also fails to call out all the ways that “normal” wasn’t working prior to the pandemic. The fault lines of the pandemic have amplified the white supremacy, economic inequality, and ecological devastation that have always been normalized within U.S. society. The disruption of the pandemic and the transition out of it offer an opportunity to repair and rebuild while centering solidarity, justice, and ecological resilience — and while following the lead of the social movements already doing this work. Our classrooms are crucial sites where students can begin to imagine what this repaired future might look like.

To watch A Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair, go to: bit.ly/TheYearsofRepair