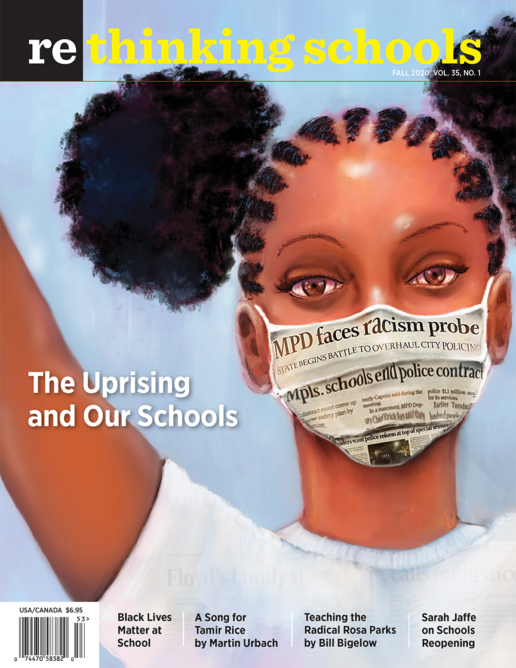

A Field Trip to the Future

Helping Students Imagine a Better World

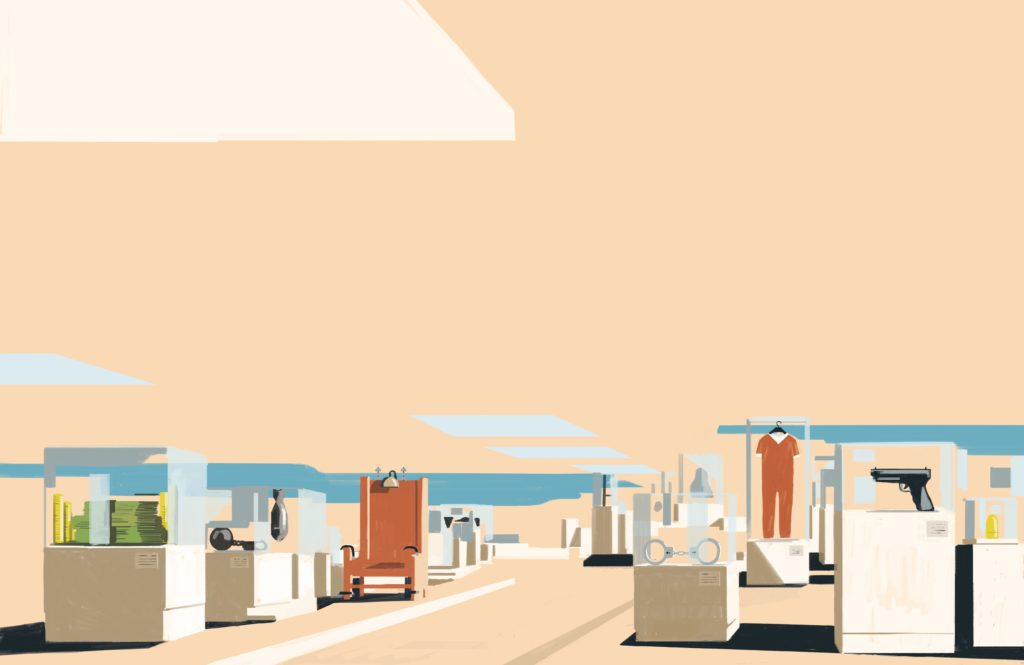

Illustrator: Fabio Consoli

“What’s the point of museums?” I ask one day to kick off class.

I teach English at a public high school in Fall River, a deindustrialized city on Massachusetts’ southeastern coast. My racially diverse, largely working-class students generally have little firsthand experience with museums: a field trip to Battleship Cove in town or, back in elementary school, one to Boston’s Museum of Science. The truth, though, is that I worry Fall River can itself feel like a museum sometimes, its old mills and factories vivid proof of better days.

“So we can see what the past was like,” Lara suggests.

“Why do we care about the past?”

“It’s interesting?”

I look over at Justin, whose knee-jerk skepticism I can count on. “Is it?”

“Hell no!” he says, earning a class laugh.

“Why do we preserve history?” I push on, smiling. “Why study it?”

“To learn from it.”

“To not repeat the mistakes of history.”

“So we can understand why things are the way they are today — like, how we got here.”

“Yes to all of that.” I plant myself at the front of the room. “Today we’re going to visit a museum,” I announce, and then over their immediate groans, “but before you tell me you’re already bored, I promise you it’s not like any museum you’ve ever been to.”

“Today,” I say, “we’re taking a field trip to the ‘Museum of Human History.’”

***

Franny Choi wrote her poem “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” back in 2015, a couple of years into the Black Lives Matter movement. I’ve been teaching it ever since.

In the poem, Choi boldly imagines a world without police, an institution she defamiliarizes by allowing us to see it through the eyes of children generations into the future. In an interview with PBS NewsHour, she explains that it grew out of her work organizing around issues of police accountability and racial profiling in Providence. I love the poem for its radical clairvoyance.

“[We] are focusing on such tiny concrete gains and victories that sometimes it’s hard to zoom out and think about what we’re actually working toward,” Choi said.

It’s intentionally hard for us to “zoom out.” Author Arundhati Roy makes clear that “empire . . . [is] selling — their ideas, their version of history, their wars, their weapons, their notion of inevitability.” In my classroom, I try to expose this false but pervasive “notion of inevitability.” I want my students to see the status quo as unnatural and therefore changeable. After all, I believe it’s my students who, with the proper tools, will struggle hardest and most effectively against “empire” and its systems of oppression.

“Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” issues the same challenge, exposing the police as anything but natural or inevitable. I teach the poem toward the end of my semester-long writing elective, in the middle of a short unit I call “Another World Is Possible.” The unit invites students to dream of a better society by having them emulate a series of rebellious mentor texts, such as Choi’s poem and Safia Elhillo’s “Self-Portrait with No Flag.” The unit serves as the fulcrum on which the course pivots: It comes after months of having written and shared stories about our lives and the world we have, but before we carry out our own local organizing campaign.

To launch the unit, we read and debate Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” (This coming year, I would like to couple it with N. K. Jemisin’s response: “The Ones Who Stay and Fight.”) We also define “utopia,” not in its pie-in-the-sky sense, but in Eduardo Galeano’s motivating one: “What, then, is the purpose of utopia?” he asks, if it’s always on the horizon. “To cause us to advance.”

After my students dream up their own utopias, we then start to work with mentor texts like “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History,” a poem that feels more relevant than ever. The twin pandemics of COVID-19 and unabated racist state violence lay bare the tragic inadequacy of accepting “the way things are” in our country, where free health care is not universally guaranteed, where Black Americans like George Floyd continue to be lynched.

Although the lesson I describe here took place before Floyd’s murder, I know that — in the wake of his murder and the national uprising it sparked — my students will be as fired up as ever for this field trip.

***

I pass out “Field Trip to the Museum of Human History” to the class. “We’re going to listen to Franny Choi read her own poem,” I say. “As we listen the first time, just try to get your bearings. Where are we? When are we?”

I pull up the poem online and turn the lights off. “It’s creepy,” I warn. “Get ready.” Choi’s voice hisses from the speakers as she introduces “the new exhibit, / recently unearthed artifacts from a time / no living hands remember.”

“What 12-year-old,” she asks, “doesn’t love a good scary story?”

We listen. I slip Khalil a granola bar when he puts his head down. I get Sierra a highlighter when she asks for one. I notice that she highlights the lines about an object in the “new exhibit:” “a ‘nightstick,’ so called for its use / in extinguishing the lights in one’s eyes.”

After our first read, I make sure we arrive at a shared understanding of the basics: In the poem, students are visiting a museum on a field trip. The poem takes place in the future. “Ancient American society” refers to us.

“As we listen a second time,” I say, “let’s focus on the exhibit they have come to see.” I project a set of questions on the board:

- What does this poem tell us about the future?

- What was Choi’s purpose?

While we listen to Choi again, I point out key words (“police,” for example) to a few students to help them concentrate on what’s most essential.

“I get it!” someone erupts halfway through the second listen.

I hush them. “Keep listening!”

Once we finish, I have students jot down quick answers to both questions before we talk together. I kneel beside a student who looks baffled and star a few central lines:

In place of modern-day accountability practices, / the institution known as “police” kept order / using intimidation, punishment, and force.

She attempts the first question. In my experience, many students have an automatic reaction to poetry that tells them it’s too hard — inaccessible and indecipherable. This poem, regardless of how much I try to hype it, is no different.

“OK,” I begin, “what do we know about this future?”

Justin pipes up: “They don’t have police anymore.”

“Yes!” I say. “How do you know?”

“The kids are learning about things like nightsticks and handcuffs for like the first time,” Ana answers. “They don’t get what those things are.”

“And how do the students in the future feel?”

“They’re scared,” Lara says.

“How do you know?”

Courtney looks at the poem, flips it over. “Well, the kids are ‘dry-mouthed’ and their palms are ‘slick.’ They’re nervous.”

“Team,” I say, “we’re on fire. Let’s move to the second question. I want to hear from Abraham first and then Sierra about why you think the poet, Franny Choi, wrote this poem.”

Abraham’s eyes go wide. “You got this,” I tell him.

We wait. After a beat, he ventures, “She doesn’t like police?”

“True! What makes you say that, Abraham?”

“It says they used ‘intimidation, punishment, and force.’ And ‘domination and control.’ Like all these bad words about them.”

“Perfect! Sierra, what else?”

“I think she’s trying to tell us something. Like that the police are bad, but we don’t see it because we’re so used to the police.”

Ana raises her hand. I nod her way. “I think it’s about police brutality,” she says.

“Yeah, and racism,” Lara adds.

“The police are killing Black people for no reason!” Justin says.

“You all nailed it. Franny Choi wrote this poem in 2015, following the high-profile murders of Black Americans — like who?”

“Trayvon Martin.”

“Michael Brown in Ferguson.”

“Right, and of course there were huge protests there and in other places, too, like Baltimore, where Freddie Gray was killed. Like the protesters, Choi is trying to help us see that we don’t have to accept things the way they are.” I hold still. “Take me to a line in the poem that highlights this.”

Some of my students look back at the poem. Others wait for their classmates to come up with an answer. I call on someone from the latter group: “Nicole,” I prompt, “in the poem, how do you see Choi trying to show us that what we have now, in the 21st century, is not OK?”

Nicole studies the front and back of the poem. “I guess it’s weird that she calls handcuffs an ‘ancient torture instrument’ — like, that’s not how we think of them.”

“Perfect! What else?”

Sierra calls our attention to the lines “assuming positions / of power were earned, or at least carved in steel, / that they couldn’t be torn down like musty curtains.”

I exhale deeply. “I love those lines, too, Sierra, and the phrase that follows: ‘obsolete artifacts.’” I call on a couple of students to make sure we all know that vocabulary. I explain, as clearly as I can, that I think Choi is exposing what we take for granted in present-day society as inconceivable, unintelligible, and unconscionable from a future utopian perspective.

***

“OK, you all know what comes next: We’re going to write our own pieces inspired by Franny Choi’s,” I offer. We start with a brainstorm.

“The last couple of days,” I remind them, “we’ve been working with the idea of utopia. You’ve already come up with what you’d want in a perfect society. Today, I want you to brainstorm everything you wouldn’t want, everything that wouldn’t exist there.” Because I want my students to have plenty of room to develop their own politics — not parrot mine — I add, “And maybe you disagree with Choi. Maybe you believe that police would exist in a perfect society. You get to decide what you are getting rid of, OK?”

I turn on a song and float around the room. A few minutes later, I offer even more specific instructions: “I’m seeing big, abstract ideas like war, racism, homophobia, and poverty. Excellent. Now, I want us to think about the concrete artifacts that we could link to each. Like, what objects do we associate with racism?”

“The Confederate flag.” “The KKK hood.” “The chain thingies that slaves wore on their feet.”

“Manacles,” I say. “Exactly — those are all things we can touch and would make sense in a museum exhibit about racism. Which is what you’re going to dream up today.” I project an example of an exhibit description I wrote as a model, a remix of Choi’s poem that I call a “wall label.” I describe it as something that might accompany an exhibit in Choi’s museum:

In Ancient American society, an institution known as “the police” kept order. If someone broke the law, police officers would “arrest” them, meaning they would lock their hands with “handcuffs,” an ancient torture instrument, a contraption of chain and bolt. The police kept order using intimidation, punishment, and force. This punishment disproportionately fell on people of color because, in Ancient American society, there were no greater protections from police than wealth and whiteness.

I walk us through the exemplar, noting how I defined terms that might be unfamiliar to people living in the better America of the future. “You are all going to write your own wall labels. They will describe something from our society today that you don’t want to exist in the future. I want to give you one more song to brainstorm. As you’re coming up with ideas, really try to think about what from our present you would relegate, what you would banish, to the Museum of Human History.”

I move from desk to desk, supporting the students with scant lists. I make sure everyone has at least one viable exhibit idea. When the song ends, I ask students to share them, many of which emerge from their own lived experiences: prisons, heroin, schools, zoos, money, homeless shelters, fossil fuels, scales. “Don’t be afraid to steal each other’s ideas,” I encourage. “It’s all part of the process.” When Nicole suggests “cultural appropriation,” a topic we’d discussed earlier in the year, I push us to identify an object we might see in that exhibit.

“A Native American Halloween costume,” someone suggests.

“Right. I’m loving these ideas. You all are just about ready to write your wall labels.”

“The key,” I reiterate, “is to make sure you describe this object from our present as if kids in the future would have no idea what you’re talking about. It’s unimaginable to them. Remember that, just as Choi does, the way you write should make us realize that it’s totally messed up that we ever allowed ourselves to tolerate whatever it is you describe in your exhibit.” I let this sink in.

“You don’t have to reinvent the wheel here either,” I say. “I lifted language right out of Choi’s poem. You can do the same. Start your own museum labels with ‘In Ancient American society’ if you want.” I notice a few students write down that line, a helpful scaffold.

After I answer clarifying questions, I set them to work: “You’ve got 15 minutes. Let’s get it.” I put on a chillhop playlist and wait to see which students don’t put pen to paper. I give them a minute or two before I wander over. As students write, I try to offer small suggestions on how they might more closely capture the poet’s style.

“Notice how Franny Choi doesn’t assume her audience will understand the word ‘handcuffs,’” I whisper to Nick. “Your audience has no idea what money is — what it looks or feels like.” He nods and adds in a few words without ever looking up from the page.

When the timer goes off, I ask for volunteers to share.

“I’ll go,” Ana offers right away, clearly proud of what she wrote:

In Ancient American society, dark stone walls restricted those who broke the law — or those who hadn’t really done anything at all. These walls were called prison, and the people were labeled prisoners. They were confined in small rooms with steel bars and were given beds hard as rock. . . . Some were sent there for the sole purpose of being killed. They would be strapped down to cold uncomfortable chairs, usually of iron, so that the electricity that passed through the prisoner’s body would kill them with complete accuracy.

We sit, stunned, before remembering to snap. “I love how you help us to see prison and the death penalty in a whole new way here. Thank you, Ana. Who’s next?”

Lara hesitates at first, then dives in:

Zoos took animals out of their natural habitat. They were then bred in captivity, so they no longer knew natural life. They only knew confinement and being controlled. Many families in Ancient America brought their drooling, ugly kids there to stick their noses and sticky hands on the glass. The animals looked sad. It was hot, and they were mopey, knowing they didn’t belong there. There was no instinct for those animals. They lived in their cages, got hand-fed. They didn’t get to hunt. They sat there as a show for those families — as entertainment.

We snap again. “You really came for those kids,” I joke.

Nick says, “These are fire. Mine sucks.”

“Oh, please. Just share what you have, Nick. You’re brilliant.”

So he does:

In Ancient American society, something called money, a small piece of green paper with a number on it, was everything in this society. This simple object could not be eaten. You could not wear it, and you could not build anything out of it that you could live inside. The truth is, it was only given and taken as a prize in exchange for the objects you actually needed or just desired. You want or need a house? You want to visit your family in another place? You needed that piece of green paper that could be ripped easily and lose its worth. Everything was about money.

“You thought that sucked?” Lara asked him. “That was so good.” We snap in agreement.

At the end of the unit, we head to the computer lab for students to revise and polish two of the pieces inspired by the mentor texts we studied, followed by a more formal read-around. For students who choose to turn their wall labels about obsolete artifacts into final drafts, I push them to grow their ideas of what replaced them. Lara, for example, will go on to mention “the Wildlife Preservations that we have today” and document the “Animal Liberation Movement [that] began in 2098” to abolish zoos.

I wrap up class by connecting the Museum of Human History back to our unit. Another world is possible, I say, so long as we have the imagination to dream it into being and the disciplined will to fight for it.

***

Franny Choi’s poem feels freshly necessary in 2020. The racist violence facing Black Americans — a knee on the neck always — was made horrifically real for George Floyd, who, like Eric Garner and others before him, cried out “I can’t breathe” as a white police officer suffocated him on film.

The national rebellion waged in response to Floyd’s murder (and the looting of Black life and livelihood that has always defined this country) opened space for more Americans to reach for Choi’s revolutionary future. Calls to defund the police and abolish prisons moved from the left-wing fringe to the political mainstream in the United States, and Americans of all parties have had to grapple with these institutions: where they come from, what function they serve, and whether we need them at all.

In “How We Save Ourselves,” a June opinion piece published by the New York Times, Roxane Gay confessed, “If you had asked me, before George Floyd’s killing, if I believed in police abolition I would have said that reform is desperately needed but that abolition was a bridge too far. I lacked imagination. I could not envision a world where we did not need law enforcement as it is presently configured. I am ashamed. Now I know we don’t need reform. We need something far more radical.”

I believe our classrooms must be sites of radical imagination in order to seed radical change. Arundhati Roy insists, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.” I keep my ear to the ground always for this breath — a gift stolen mercilessly, again and again, from Black Americans like Garner and Floyd. By being in conversation with revolutionary mentor texts, I hope my students have the quiet chance to hear her, too — to see her take shape.

Field Trip to the Museum of Human History

By Franny Choi

Everyone had been talking about the new exhibit,

recently unearthed artifacts from a time

no living hands remember. What twelve year old

doesn’t love a good scary story? Doesn’t thrill

at rumors of her own darkness whispering

from the canyon? We shuffled in the dim light

and gaped at the secrets buried

in clay, reborn as warning signs:

a “nightstick,” so called for its use

in extinguishing the lights in one’s eyes.

A machine used for scanning fingerprints

like cattle ears, grain shipments. We shuddered,

shoved our fingers in our pockets, acted tough.

Pretended not to listen as the guide said,

Ancient American society was built on competition

and maintained through domination and control.

In place of modern-day accountability practices,

the institution known as “police” kept order

using intimidation, punishment, and force.

We pressed our noses to the glass,

strained to imagine strangers running into our homes,

pointing guns in our faces because we’d hoarded

too much of the wrong kind of property.

Jadera asked something about redistribution

and the guide spoke of safes, evidence rooms,

more profit. Marian asked about raiding the rich,

and the guide said, In America, there were no greater

protections from police than wealth and whiteness.

Finally, Zaki asked what we were all wondering:

But what if you didn’t want to?

and the walls snickered and said, steel,

padlock, stripsearch, hardstop.

Dry-mouthed, we came upon a contraption

of chain and bolt, an ancient torture instrument

the guide called “handcuffs.” We stared

at the diagrams and almost felt the cold metal

licking our wrists, almost tasted dirt,

almost heard the siren and slammed door,

the cold-blooded click of the cocked-back pistol,

and our palms were slick with some old recognition,

as if in some forgotten dream we did live this way,

in submission, in fear, assuming positions

of power were earned, or at least carved in steel,

that they couldn’t be torn down like musty curtains,

an old house cleared of its dust and obsolete artifacts.

We threw open the doors to the museum,

shedding its nightmares on the marble steps,

and bounded into the sun, toward the school buses

or toward home, or the forests, or the fields,

or wherever our good legs could roam.

Franny Choi is author of the poetry collections Soft Science and Floating, Brilliant, Gone. She is a Bolin Fellow in English at Williams College. Visit her website at frannychoi.com. This poem originally appeared in a PBS NewsHour online feature.