Short Stuff 27.1

Illustrator: Laura A. Oda/Oakland Tribune

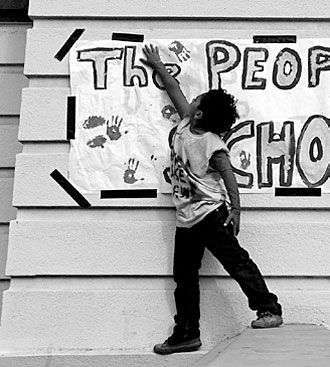

PEOPLE’S SCHOOL AT OAKLAND’S LAKEVIEW ELEMENTARY

Parents and children, teachers, and community activists occupied an Oakland neighborhood elementary school for almost three weeks this summer to try to keep it from being closed.

Back in 2011, Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) Superintendent Tony Smith and the school board agreed on a plan to close 25-30 schools in Oakland. The first five elementary schools were scheduled to close June 2012.

Therese Pecot is the grandmother and guardian of three students at one of those schools, Sante Fe Elementary: “They are now trying to close the fifth school in my neighborhood—and all five of these schools have served mainly African American children. This is racial discrimination, plain and simple.”

According to Lakeview Elementary School parent Joel Velasquez, the community did everything it could to save the schools: “After organizing parents and teachers from the five schools, we organized marches to board meetings, rallies with more than 3,000 people, and meetings with board members, the superintendent, and a list of administrators. The end result was nothing short of a waste of time for all of us.”

Velasquez added: “Closing elementary schools is traumatizing our kids. It is sending them the message that their education is not important.” So the group decided to send a different message.

On June 15, as students and teachers left for the summer, the group (which now included supporters from Occupy Oakland) erected tents on the Lakeview grounds and started a freedom school inside. Velasquez described their People’s School: “It was a free and successful summer program run 100 percent by volunteers and focused on a social justice platform. The program included art, music, organic gardening, environmental science, and curriculum that expanded every day. Volunteer teachers poured in from Oakland and beyond. Parents came daily to sign their children up and we held events on the weekends for the community. The community fed us and dropped off supplies every day for the children.”

Three weeks later, on July 3, the Oakland police came at 4 a.m. to break up the encampment.

Despite the forced end of the People’s School, the community has vowed to continue the fight. Plans include a campaign for progressive school board members.

“This was a school that had stood for almost a century here in Oakland educating children, a school that was a second home for two of my children for the past 10 years, the kind of school that belongs in every community,” Velasquez said. “This is what pushed an average everyday parent to say enough is enough. We can no longer just hope for change. We have to do something for change to happen.”

Based on reporting by Joel Velasquez, M Shane, and OccupyOakland.

SCHOOL-TO-PRISON PIPELINE TRAINING

Breaking the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Bringing Restorative Justice to Our Schools was a three-day summer training organized by Teachers Unite for New York City educators, youth organizers, advocates, and others seeking strategies for rethinking school discipline.

Participants discussed the history of schools in the United States, from Puritanical views of children as evil to the genocidal boarding schools for Native American youth, the Reagan-era introduction of zero tolerance, and the history of indigenous and black resistance against an education system that is often a model of social injustice.

Teachers Unite has been working with the Dignity in Schools Campaign to promote model approaches to positive discipline in pilot schools. So at the training, Maria Hantzopoulos (see “Deepening Democracy,” Fall 2006) shared insights from students about their experiences in a school that uses fairness committees: The students said it changed the way they saw privilege, justice, and punishment in society at large, and changed their relationships with teachers and peers. Educators who started fairness committees in their schools helped brainstorm strategies for implementation in different school settings. One Bronx high school teacher noted: “Discipline itself is inextricable from ideas about community and accountability in schools. So the process of clarifying our values and relationships as individuals, as teachers, and as whole schools is urgent and fundamental to ‘fixing discipline.'”

A major goal of the workshop was to help teachers connect classroom activities with policy advocacy. According to Sally Lee, executive director of Teachers Unite, “By joining youth and allies to fight against zero tolerance policies and for restorative practices, educators can move the education system toward a vision of social justice.”

Based on reporting by Sally Lee at Teachers Unite.