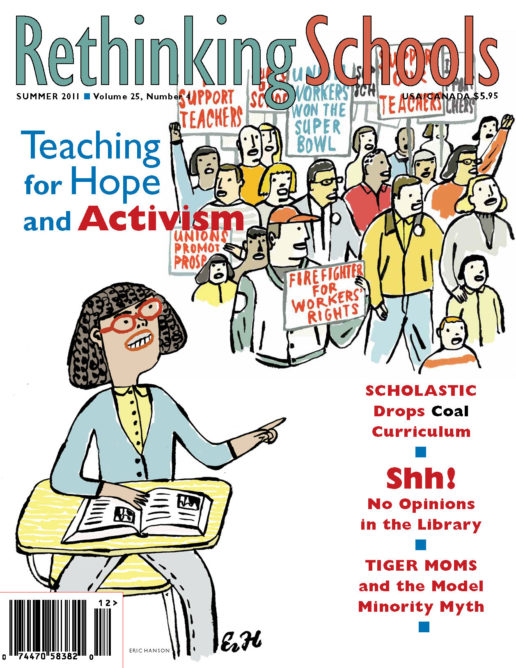

Preview of Article:

Teaching and Learning in the Midst of the Wisconsin Uprising

Illustrator: Kate Lyman

It all started when my daughter, also a Madison teacher, called me. “You have to get down to the union office. We need to call people to go to the rally at the Capitol.” I told her I hadn’t heard about the rally. “It’s on Facebook,” she responded impatiently. “That’s how they did it in Egypt.”

That Sunday rally in Capitol Square was just the first step in the massive protests against Gov. Scott Walker’s infamous “budget repair bill.” The Madison teachers’ union declared a “work action” and that Wednesday, instead of going to school, we marched into the Capitol building, filling every nook and cranny. The excitement mounted day by day that week, as teachers from throughout the state were joined by students, parents, union and nonunion workers in the occupation and demonstrations.

Madison teachers stayed out for four days. It was four exhilarating days, four confusing days, four stressful and exhausting days.

When we returned to school the following week, I debated how to handle the days off. We had received a three-page email from our principal warning us to “remain politically neutral” as noted in the school board policy relating to controversial issues. We were to watch not only our words, but also our “tone and body language.” If students wanted to talk about the rallies, we were to respond: “We are back in school to learn now.”

That morning, as I watched the students file off the buses, I wondered about their responses to the Capitol protests. Since 70 percent of the students at our school come from low-income households, I guessed that most of the families would be supportive of fighting for teachers’ and other workers’ rights, and for public schools. I wasn’t sure how informed they’d be about other aspects of the governor’s proposals. I was fairly certain that most students had some knowledge, if only from the media, of what had happened on their days out.

A kindergartner confirmed my hypothesis when he marched off the bus shouting “Kill the bill!” In fact, some students had been at the protests with their parents; many had seen the demonstrations on the news; the others were wondering what the teachers were doing on their days off.

My class came in with questions and comments about the protests. They all wanted to speak at once. After morning greetings in the 10 languages that my 2nd- and 3rd-grade students speak, I asked them to raise their hands if they had a comment about the Capitol protests. Carlos said: “I don’t like the governor. People born in Mexico—he’ll take off their credit. He’ll send them back to Mexico.” Joshua, who loves math, said that there were 70,000 people at the place were the governor works. “Hey, Kate,” he said enthusiastically, “you could make that into a math problem!” Kalia was proud that her mother and three older sisters were there with a Hmong contingent. She said, “Scott Walker dropped out of college, but he’s cutting people’s money.” Carlos added that he knew that schools were closed because the governor was raising medical bills.