Puerto Rican Students Win Major Victory

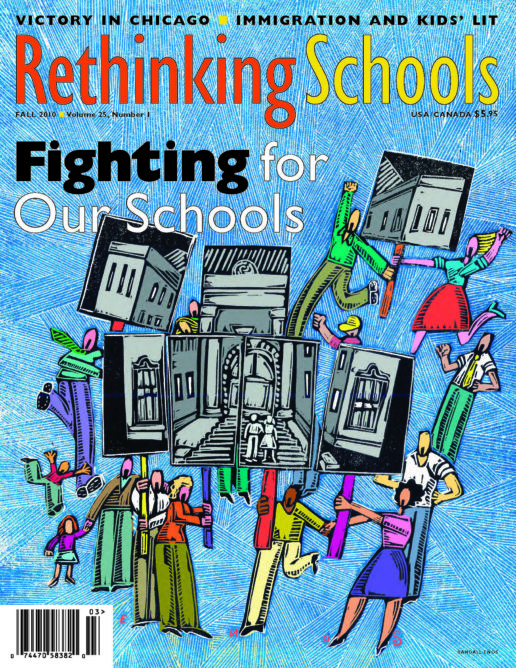

Illustrator: ©2010 RICARDO AUDUENGO | ASSOCIATED PRESS PHOTO

After a two-month strike at all 11 campuses of the University of Puerto Rico (UPR), students won the most impressive victory in the history of the university—and one of the most heartening in the current fight for public education. In June, the Board of Regents was forced to agree to the central demands of the students: the continuation of a variety of tuition waivers, the cancellation of a 50 percent fee hike, the rejection of initiatives to privatize the university, and amnesty for everyone involved in the strike.

The strike began April 21 as an occupation at the main Río Piedras campus when the university president refused to budge on student demands to continue the tuition waivers, say no to privatization, and restore $100 million in budget cuts. Students camped inside the university’s gated fence and stormed the gates from within early in the morning, overwhelming the surprised security guards. Within a week, all 11 campuses were on strike. Shortly after the occupation began, unions and community groups that ordinarily protest the governor’s yearly budget address at the capitol building instead assembled outside the Río Piedras campus main gate—to show their solidarity with the students. Support for the strike was also strong among faculty, staff, parents, and the community.

A Culture of Resistance

From the beginning, artistic expression was central to

the protest. Students participated in street theater, mass bench-painting campaigns, puppet-making workshops, poetry, and musical gatherings. Students at several campuses broadcast “radiohuelgas” (strike radio). One student commented, “The strike hasn’t closed the university; rather it has given it life.” Many classes continued to meet outside university grounds or over the internet.

“The 2010 student strike shines because of its particularities,” wrote blogger Nahomi Galindo-Malavé last May. “For the first time in history there is a systemwide strike, and everyone shouts—every time they can—‘11 campuses, one UPR.’”

UPR has a long history of student strikes, but many activists say this is the most successful, both for its immediate results and because of its success in organizing and integrating large numbers of students in the process. According to Galindo-Malavé, although women were not a majority on the national negotiating committee, “the strike has a woman’s face. They are the main organizers on the campuses.” This is also the first time there was a visible presence of lesbian/gay/genderqueer activists. Rainbow flags were flown from the beginning of the occupations, the strikers celebrated the International Day Against Homophobia in May, and a gay rights organization served on the negotiating committee.

The strike was able to generate broad sympathy among students, the community, and even much of the media, partly because of the unpopularity of the current right-wing government in Puerto Rico. But, according to the website La más mínima diferencia/the slightest difference, the most critical elements to the strike’s success were the commitment to broad, democratic participation of many different political perspectives, and years of organizing on the campuses following an unsuccessful strike in 2005. In that case, students were angry enough to vote to strike, but grassroots organizations weren’t strong enough to provide a structure for organizing to win.

The Government Strikes Back

Only two weeks after the students’ victory, the government retaliated. First, Puerto Rican Senate President Thomas Rivera Schatz expelled all journalists from the senate session. Then the police, including the anti-riot squad, attacked demonstrators and journalists in front of the capitol building. Once no one was around to watch, the legislature approved a new measure that eliminates student assemblies and substitutes an internet voting system. “I don’t think there is any doubt that the intention of this government is to set back civil rights,” Judith Berkan, law professor at UPR and InterAmerican University in San Juan, told Maritza Stanchich of the Huffington Post. Another clear intention was to break the back of the student movement.

The struggle to save accessible higher education in Puerto Rico, fought in the context of the worst economic crisis the island has faced since the 1930s, will clearly continue. The students say they’re ready. “We may not hold the power but we have the willpower,” law student Aníbal Núñez told Stanchich. “And given the choice, I prefer the latter.”

REFERENCES

Galindo-Malavé, Nahomi. “Una Huelga Particular.” La más mínima diferencia/the slightest difference. May 26, 2010. www.jalaguarta.com.

Stanchich, Maritza . “University of Puerto Rico Student Strike Victory Unleashes Brutal Civil Rights Backlash.” The Huffington Post. July 4, 2010. www.huffingtonpost.com/maritza-sanchich-phd/university-of-puerto-rico_b_635090.html.