Learning About the Unfairgrounds

Illustrator: University of Washington Special Collections: Clifford Howard

Special Collections: Clifford Howard

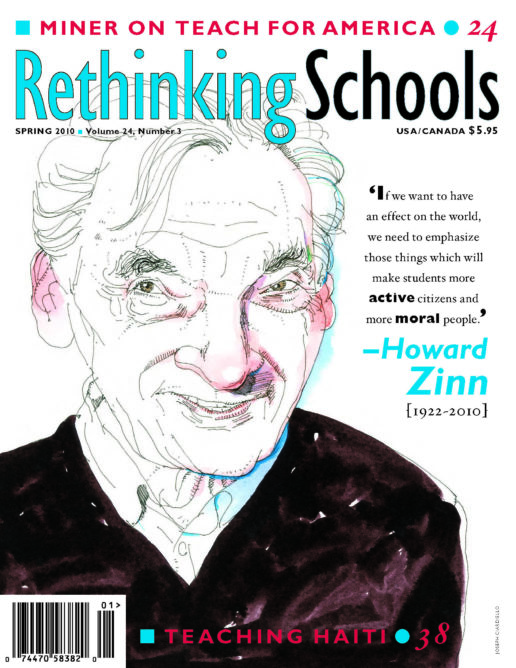

Japanese American evacuees at the

Puyallup Civilian Assembly Center,

known as Camp Harmony, 1942.

The Puyallup Fair, 35 miles south of Seattle, Wash., ranks as one of the 10 largest fairs in the world. When I was growing up, every September my mom, dad, brother, sister, and I drove the 20 minutes from our house to the fairgrounds to spend the day. We kids looked forward to cotton candy and bumper car rides. Mom and Dad held our hands as we ooh-ed and ah-ed over 200 pound pumpkins. There were magic shows, animals to pet, cows to milk, and the World Famous Earthquake Burger.

Up until several years ago, local school districts released children early on the second or third Wednesday of the school year with free tickets to attend the Puyallup Fair. Even today districts distribute free admission tickets to schoolchildren. For people who grow up in this area, the fair is a tradition.

I’m sure I was not more than 2 years old the first time I attended the fair. Still, it was another 10 years before I learned some of the fairgrounds’ history. In middle school, I was close friends with a girl whose father was Japanese American. In 1988, she told me that her grandmother would receive several thousand dollars from the government as part of an apology for detaining her and her family at the Puyallup fairgrounds during World War II. I couldn’t believe that she had the story straight and convinced myself that she must have misunderstood her father. It was impossible that my fairgrounds,those hallowed grounds of tradition, had been used for something unjust. It was not until college that I realized that she was right. During World War II, the land on which the fairgrounds stood was dubbed the Puyallup Assembly Center, or, as some referred to it in an attempt to mask the nature of the place, Camp Harmony.

Executive Order 9066

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, U.S. officials issued a series of proclamations that violated the civil and human rights of the vast majority of Japanese Americans in the United States—ostensibly to protect the nation from further Japanese aggression. The proclamations culminated in Executive Order 9066, which gave the secretary of war the power to “prescribe military areas” wherever he deemed necessary for the security of the nation. This order provided license to incarcerate more than 120,000 Japanese Americans in internment camps (as well as several thousand Italian Americans and German Americans). Most of the people held in the camps were taken from the West Coast, where the feds believed “the enemy within” might be able to alert the Japanese military of U.S. vulnerabilities via a short wave radio or perhaps a lit cigarette.

Camp Harmony was one of 18 Civilian Assembly Centers—temporary holding areas for the Japanese Americans who were rounded up for incarceration. More than 7,000 people were held at Camp Harmony. Most were from the Seattle area, but some were brought from as far away as Alaska. It did not take long for the new residents to realize they were living in stalls that had previously housed livestock.

Once the government completed construction of the more permanent War Relocation Centers (commonly referred to as “internment camps”), authorities boarded those being held in the assembly centers onto buses and trains and shipped them to the internment camps. In all, 10 War Relocation Centers were built between March and October of 1942, located as far west as Tule Lake, Calif., and as far east as Desha County, Ark. Many people were held until 1945, three years after the first camps opened.

Civil Rights in the Northwest

When the day came in early September for me to distribute Puyallup Fair tickets to my 4th-grade class, I asked if any of them knew the history of the fairgrounds beyond its use as a place to display large vegetables. No one raised a hand. I took this as an opportunity to investigate with my class some of the local roots of a national injustice.

There is something mythological about the Civil Rights Movement. Over the years I’ve discovered that most children in my classes think that civil rights struggles were fought long ago in far away places. Here in the Northwest, the movement is often revered as a unique time in our nation’s history when brave souls spoke truth to power in distant places like Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. However, teaching about civil rights struggles as only occurring Someplace Else disempowers students. I wanted my 4th graders to understand that injustice has played a role in the shaping of our community, and that the responses of people being treated unfairly do not always look the same. I wanted them to see that sometimes activism against injustice can be as quiet as refusing to answer a question. My hope was that the class would understand that it was unfair to assume that Japanese Americans as a group were a threat to the safety of the country, based on an attack by a foreign nation. Further, I wanted them to see that blanket incarceration was a violation of human rights.

We began by reading several children’s books. These all provided an accessible way for the children to see how fundamentally unfair it was for thousands of people to be persecuted based solely on their ancestry. We discussed how the families’ civil rights were violated. We also looked at how the voices of those incarcerated were hopeful and resistant.

To provide the class with a deeper understanding of the issues, I wanted to include a longer work of literature. I found the book Thin Wood Walls by local author David Patneaude. I read the novel and found it to be a valuable look at the many ways incarceration affected people in the Northwest. The protagonist is Joe Hanada, an 11-year-old boy living in Auburn, Wash. during World War II. The FBI takes his father prisoner and holds him, away from his family, for two years. Eventually the government sends the remaining Hanada family—Joe, his mother Michi, his paternal grandmother, and his older brother Mike—to the Tule Lake internment camp. While the novel focuses on Joe’s experiences, Patneaude does an excellent job of showing how, even within the Japanese American community, people reacted differently to government actions.

A Tea Party to Introduce a Challenging Novel

The book has a recommended reading level of age 12 and up, and my class included 9- and 10-year-olds. To help them better understand the nuanced differences in how the characters reacted to Executive Order 9066, I held a “tea party” (for instructions on tea parties, see “The U.S.-Mexico War Tea Party” in Rethinking Schools’ A People’s History for the Classroom). A tea party takes a novel or historical event and assigns each student a literary or historical character. Students circulate in the classroom and initiate conversations, introducing themselves (in role) and asking questions of other characters.

I picked out 21 characters from the novel and wrote up “persona cards.” Here are a few examples:

Joe Hanada

I am 11 years old and live in Auburn, Wash., in the early 1940s. My parents are Japanese. I was born in the United States, so am a U.S. citizen. I enjoy playing basketball, baseball, and marbles. My best friend is Ray O’Brien—an Irish American boy who is in my class at school. I love to write and hope to be an author when I get older. I am Nisei (second generation Japanese in America). When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the government arrested my father and moved my family to two different camps. I keep a journal to write about my feelings.Michi Hanada

I am the mother of Joe, 11, and Mike, 16. I was born in Japan but came to the United States 20 years ago with my husband. While by law I cannot become a citizen, my children are citizens because they were born on U.S. soil. I have worked hard to make sure that my household is beautiful and to provide what my family needs. I do everything I can to keep my spirits up and fill the shoes of my husband, who has been arrested by the FBI. The government has still not charged him with any crime. I do not know when he will return to our family.David Omatsu

They call me a No-No Boy. Let me tell you why: The government gave a questionnaire to all of the Japanese Americans at the camp. Question 27 asked if we would agree to fight for the United States in the war. I said no—how could I be in the Army when my whole family is jailed in this camp? Question 28 asked if we would “forswear any form of allegiance to Japan.” I answered no because I was born in the United States—I’m an American! But anyone who answered no to both questions is called a No-No and sent to a special prison camp.Mr. Langley

I live on the same block as the Hanada family. I am not surprised to hear that Japan has attacked the United States. I knew they were a no-good country. I think all the Japanese should be rounded up and sent back to Japan. My son Harold goes to school with one of the Hanada boys and I told him to stay away from that traitor’s family. I don’t want my own son to catch any of that disloyalty.Sergeant Sandy

I joined the army because I knew it would help my future. I have a wife and I’m excited to begin building a family. I have been stationed as a guard at the Tule Lake Relocation Camp in Northern California. I’m sad because I think that the government has made a bad decision to lock up so many innocent people. However, I have my orders and I will not disobey. I try to get to know as many of the families at the center as I can.

I handed out the persona cards and gave the children a worksheet to guide their interactions during the tea party. Then I had them write, from their characters’ standpoints, answers to the following questions: “How do you feel about the war with Japan?” and “What is your opinion about how Japanese Americans were treated by the U.S. government? Why do you feel that way?”

Once the children finished writing, we began the tea party. I asked the students to find other individuals who could help them answer the questions on their worksheets. For example: “Find someone who feels the same way you do about the Japanese American experience during World War II. Who is this person? What do you agree about? Why do you think this person feels similarly to you?” “Find someone who feels differently than you do. Who is this person? How is this person’s opinion different than yours? Why do you think you feel differently?”

Following the tea party, I asked students to reflect in writing about what they had learned.

As I circulated throughout the activity, I overheard snippets of conversations and wrote down key phrases. I was pleasantly surprised that several children seemed able to internalize aspects of their characters:

Shawna (as Michi Hanada): “This is sad because they took my husband away.”

Henry (as Mrs. O’Brien, a family friend): “I am sad and sorry about what happened to the Hanada family. I wish there was something I could do to help, but I can’t think of anything to help them.”

Kim (as David Omatsu): “I am angry because I was treated like dirt, just because I am Japanese American.”

Karen: (as Sergeant Sandy): “I think what we are doing to the Japanese Americans is wrong, but I am doing what is right for my future by staying in the army.”

The tea party was invaluable in introducing the children to some of the complexities of the period. It helped equip most students to comprehend Thin Wood Walls as I read it aloud to them. The variety of roles in the book allowed the children to realize that there were many, many ways people reacted to what was happening. Some of the Japanese Americans, despite being forced to leave their homes and livelihoods, felt it was their duty to do as their government asked. Some felt their rights were being violated, but did not know how they could resist alone. Others felt that the best way to prove loyalty was to enlist and fight in the war for the United States. Still others openly resisted the policies of incarceration and discrimination.

Throughout our reading, the children engaged in a series of activities and reflections. As I read, they sketched scenes I described, “drawing along” to increase comprehension. Joe Hanada saw himself as a writer and kept a journal, so I had the children write from the perspective of various characters in the book. I tried to provide enough concrete information to make these types of activities accessible to all children. Several children in the class spoke English as a second or third language and needed more support than I initially provided in terms of vocabulary and context.

Over the next few weeks, I incorporated aspects of what we were learning into as many lessons as possible. For example, we used data from the incarceration camps to do plot and line graphs in math. I obtained the numbers of people held in the various camps and wrote the names of the camps on the x-axis of a graph and the numbers up the y-axis. The children then worked to construct tables and graphs that showed population distribution in the camps throughout the western United States. This activity opened up opportunities to discuss big numbers and led to a deeper understanding of place value. Here was a direct connection for my students between important mathematical concepts and a chapter in U.S. history.

A Mock Trial

During the Japanese American incarceration, there were three attempts to find Executive Order 9066 unconstitutional. I chose two of the cases to conduct mock trials in my class: the cases of Gordon Hirabayashi, whose story is told in the documentary A Personal Matter, and Fred Korematsu. Hirabayashi and Korematsu were convicted in federal court of violating curfew and refusing to relocate in 1942 and 1943, respectively. Both men were re-tried over 40 years later: Hirabayashi’s conviction was overturned; Korematsu’s case was vacated and his name cleared.

The children wanted to find the men not guilty, and they conducted their court based on their beliefs of what was right and wrong. It took a lot of coaching to get them to see the cases from the perspectives of government agents, lawyers, and the Supreme Court of the early 1940s. Ultimately the class found both men not guilty, and defended their judgments based on the Constitution. They were stunned to find that the U.S. government had been so negligent in its dispensing of justice more than 60 years earlier. I told them that it wasn’t until the passing of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 that the government admitted that “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and failure of political leadership” fueled the mass incarceration of innocent people during World War II.

The unit culminated with a trip to the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle. I prefaced this trip by sharing stories about Wing Luke, who fought for equal housing rights in Seattle from the 1950s until his death in 1965. Although Luke’s name is not as well known as that of Martin Luther King Jr. or Rosa Parks, the work he did to combat anti-Asian discrimination was groundbreaking. Prior to his activism, Asian Americans were confined to living mostly in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, much as African Americans were restricted to the Central District.

Luke ran for and was elected to the Seattle City Council in 1962 and was instrumental in passing the 1963 Open Housing Ordinance, which established punitive provisions for racial discrimination in the selling or leasing of real estate. A special exhibit at the museum about World War II helped my students build on what they had learned and broadened their understanding of the impact of racism on the community.

Ultimately, this curriculum taught several valuable lessons. The first lesson was that, even though the signs of past discrimination are not obvious when we walk down the street, the history of our region holds evidence of injustice. The second lesson was a deeper understanding of human rights and the need that we all have to be treated with respect and justice. Students who had never experienced racial discrimination themselves learned that it exists even in their own backyards. Finally, students learned that there are many ways people react to and resist injustice: sometimes overtly by challenging laws in court, sometimes quietly by refusing to comply, sometimes by an act of kindness or empathy.

The notion that our nation’s struggles for civil rights took place only in the South was replaced with the knowledge that people here in the Northwest, too, have been active in creating the world we live in today. I hope that students in my class learned that, even though we say we are “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” the U.S. government has acted against its people. We must demand justice when it is being violated; otherwise, we may find ourselves in the same place we were 60-plus years ago.

Children’s Books About Japanese Americans During World War II

Baseball Saved Us

by Ken Mochizuki

The story of a Japanese American family that is interned and ends up building a baseball diamond in the camp. Ultimately, it is the story of how, even when forced to live within the confines of an internment camp, people find ways to retain their spirits and create community.

Flowers from Mariko

by Rick Noguchi and Damien Jenks

This book illustrates the difficulties that many families experienced after being held in the camps. Often, homes had been sold, businesses ruined, and possessions lost. In this story, the child, Mariko, helps her family build upon a dream that might easily have died after three years of internment.

The Bracelet

by Yoshiko Uchida

The author of Journey to Topaz writes here of a friendship strong enough to withstand the trauma of being forced to leave one’s home and live in an internment camp. This book demonstrates that there were allies and friends both inside and outside of the camps who expressed solidarity through acts of kindness.

When Justice Failed: The Fred Korematsu Story

by Steven A. Chin

Fred Korematsu was rejected for military service in 1941 because of his Japanese ancestry and then fired from his job in the shipyards for the same reason. He refused the order to evacuate from his home and go to an internment camp. This short biography recounts his life and his struggle against unfair treatment. Appropriate for upper elementary grades.

RESOURCES

Tea Party

Patneaude, David. Thin Wood Walls. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

De Graaf, John. A Personal Matter (DVD documentary).

The Constitution Project. (Available from the Center for Asian American Media), 1992.

Yamaguchi, Jack. This Is Minidoka (VHS documentary). Nagai Printing, 1989.

The Densho Project. An online archive of original sources for the study of the internment of Japanese Americans (www.densho.org).