Teaching the Reconstruction Revolution

Picturing and Celebrating the First Era of Black Power

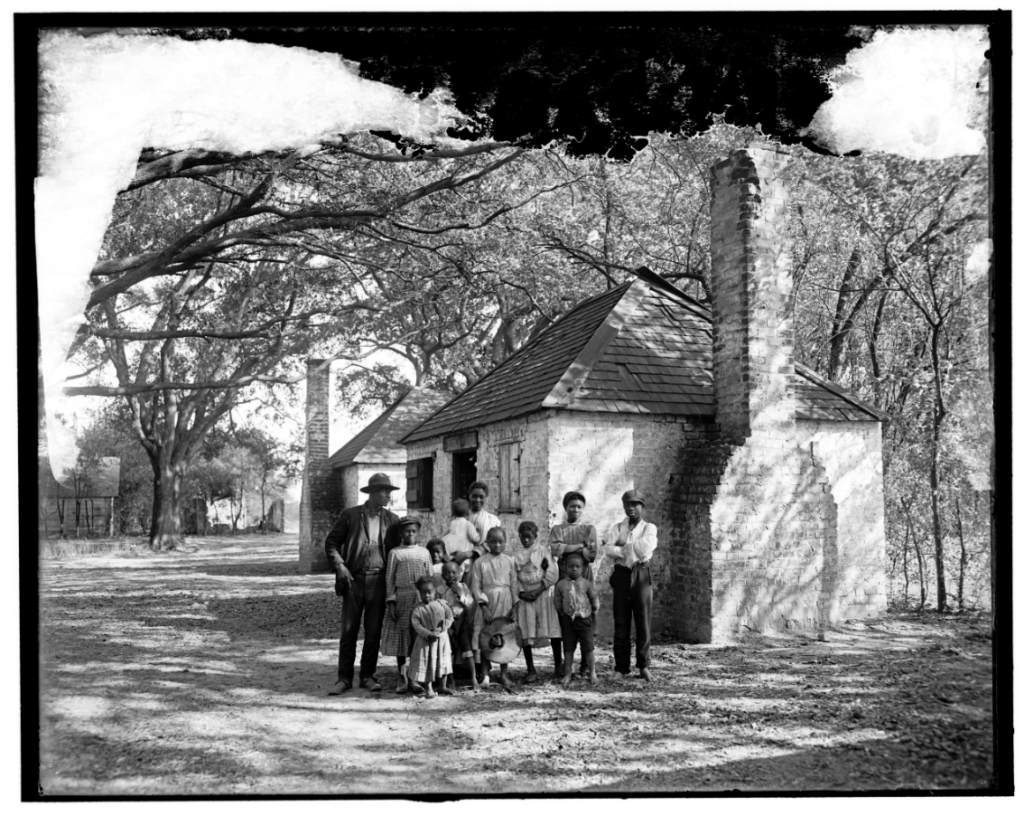

A Black family at the Hermitage in Savannah, Georgia.

“I learned there was an era of Black power that I didn’t even know existed,” Sean wrote. “That there was a MAJOR Black power movement in the 1860s and 1870s, is so exciting to me!” Joel added. “As a Black student, I’m really happy to be learning about it . . . because everyone thinks that it was only in the 1960s when there was a powerful Black rights movement.”

I had asked my African American history students at Philadelphia’s Central High School to summarize what they had learned from our unit on Reconstruction and whether they thought it was important for students to know about this era and why. The answers I received were a testament to how empowering learning about Reconstruction can be for students — in a way that emphasizes the dramatic struggles and successes of the era.

Layla wrote, “It’s important for students to learn about this era because it’s not as simple as slavery being abolished and then Jim Crow laws were implemented — there was a time period in between. This period teaches us that progress that is made can be undone.” And Tevin added that “learning about Reconstruction teaches us that if people come together, they can bring forth major political reforms — even changes to the Constitution.”

The conclusions my students came to about the Reconstruction era were conclusions that many drew at the time and many historians have drawn since. Ironically, it was racist journalist James Shepherd Pike who captured the revolutionary dimension of Radical Reconstruction when, writing in 1873 about the Black-majority legislature in South Carolina, he saw “the spectacle of a society suddenly turned bottom side up.” Pike was horrified. Historian Lerone Bennett Jr. analyzed Pike’s reaction in his book Black Power U.S.A.: The Human Side of Reconstruction, 1867–1877: “Nothing in Pike’s past life had prepared him for such a turnabout . . . Black people in charge, running things, and white people, ‘cowed and demoralized’.”

Indeed, the period commonly referred to as Radical Reconstruction was precisely one of those rare moments where poor people grasped the levers of power. Textbooks often focus on the few Black people who made it to the U.S. Senate or House of Representatives. Although these are certainly some of the most dramatic symbols of the revolution that swept through the South, it’s the smaller local positions — Black jurors, judges, tax assessors, sheriffs, county commissioners, school board members — that give a sense of the drastic ways Radical Reconstruction transformed the day-to-day lives of most Black people. As historian Steven Hahn writes, “Never before — and rarely again — in the history of the United States would such a substantial section of the working class have the opportunity to contest the power of their superiors in the formal institutions of governance that affected their lives most directly. It proved to be a turbulent and telling experiment in the meaning of democracy.”

And beyond those who gained official titles, the actions of everyday people — demanding better treatment on the streets and on the plantations, organizing self-defense against reactionary whites, protecting families and allies, protesting for better treatment — reveal the many attempts to make society anew and prevent the old racist relations from returning.

Although this period is paralleled by the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and ’70s in the sheer numbers and boldness of Black people fighting racist practices and contesting for power, there are far fewer resources that give students — especially K–12 students — a sense of the revolutionary upheaval that swept the country during the late 1860s and ’70s. To address this, I created two lessons that help students understand, imagine, and celebrate this moment as the first era of Black power in the United States.

I’ve taught a version of these lessons at several different high schools, but most recently at Central High School, one of Philadelphia’s public academic magnet schools. Central’s student body is a little over two-thirds students of color and around the same percentage low-income. The following classroom stories are from my 10th-grade African American history course, a required course for all Philadelphia high school students.

These lessons occurred in the middle of my Reconstruction unit during the third quarter of the year — after we’d discussed the experiment of redistributing land to freedmen, the disastrous return to white supremacy under Andrew Johnson’s Presidential Reconstruction, the revolutionary conventions of 1868–1870 that rewrote the state constitutions of the South, and the radical implications of the 14th and 15th amendments.

Reconstruction Improvisations: Envisioning Black Power

When students entered the class, I divided them into six groups. I explained the context for what we’d be doing: “After participating in the Reconstruction conventions that rewrote the constitutions of the Southern states, and securing the 15th Amendment, Black people were more and more confident in their ability to define the meaning of freedom. Just 10 years earlier, for most Americans it seemed inconceivable that slavery would end within a decade, let alone that Black people would be able to vote and hold office. But what had previously seemed impossible, was now reality throughout the South. It was a new day and Black people were determined to no longer live under the old conditions.” I continued by explaining the task: “For this activity, I’ve assigned each group two improvisations that you will perform tomorrow in the class. The purpose of these improvisations is to try to get a sense of how Black people held and contested for power during Reconstruction.”

Given recent headlines of poorly designed and sometimes traumatic and racist role plays, teachers might hesitate to have students perform improvisations in class. But there is also an important anti-racist, social justice tradition of role playing for liberation in the Freedom Schools set up by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s and Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed in Brazil in the 1970s. Furthermore, there is no risk-free pedagogical strategy — especially when discussing racism and exploitation. But as an anti-racist teacher, I try to anticipate and prepare for potential risks as best as possible and honestly address anything that feels uncomfortable to me or my students in the moment or after the fact.

My students understand that our classroom is a place where we uncover Black history, to better fight for an anti-racist future.

As my colleagues at the Zinn Education Project have argued, “Students’ respectful, historically grounded role-taking must happen in a classroom where students are used to talking and thinking explicitly about race and justice. . . . Students need to understand that any role play is embedded in a broader curricular project to explain the origins and persistence of social inequality in the United States, and to equip students to see themselves as potential change makers.” These improvisations occur well after our classroom culture has been established. My students understand that our classroom is a place where we uncover Black history, to better fight for an anti-racist future.

All the improvisations are based on real situations and aim to help students take stock of the revolutionary transformation of Black life during Reconstruction. For example, one improv helps students grapple with the raised expectations electing Black judges and sheriffs created despite a justice system founded on white supremacy:

Background: A white person shoots a Black person during a fight at the local ferry (passenger boat) in broad daylight. The white sheriff refuses to arrest the murderer. Improvisation: The Black community gathers to discuss how to respond. There is a newly elected Black judge and they think if they can get the shooter arrested, they might be able to get justice for the victim. Some propose that the community conduct a “citizen’s arrest.”

I emphasized that students should not act out the “background” — which is often more action oriented — but should perform the part labeled “improvisation.” I also told students that they did not have to write a script (although some chose to), but that they needed to have an outline — a basic sense of who would play what role, and where they wanted each improv to begin and end. Would there be one or multiple scenes? If the improv was a discussion, as most were, what were some of the points of disagreement that would create tension and what would the final resolution be? I also encouraged them to think about some of the key points about how Reconstruction changed society that they wanted to get across.

As students read and considered how to best perform their improvisations, I circulated among the different groups to answer questions, listen to their ideas, and sometimes suggest ways they might perform the skits. At first, students might have anxiety about performing in front of their peers, but I’ve found that giving them at least one full period to prepare helps calm their nerves. Students also chose roles they felt most comfortable performing.

After students had a rough outline for their improvisations, I encouraged them to practice once or twice at their desks to make sure they were ready to perform the next day. Although most improvs ask students to perform discussions amongst members of the Black community and/or with anti-racist white allies, there are a few that involve confrontations with racist employers and some, like the example above, that students might add a scene of confrontation to (acting out the citizen’s arrest). Because I thought those improvisations might be the riskiest to perform in the classroom, I made sure to check in with the groups assigned to those and get a sense of what they were planning, sometimes sitting in on their rehearsal. If, for example, students decide it might be “funny” to have the one Black student in their group play the racist employer, I emphasize the point of the improvisations is not to make others laugh, and encourage students to rethink their plan. It can also help to encourage Black students to take the lead in assigning group roles.

The next day, after giving students time to check in with their groups, I explained that after the performances I would ask them to write a piece of historical fiction from the point of view of a character in one of the improvisations. It might be a character that they portrayed or a character in a skit performed by a different group. I encouraged them to take notes as they watched, writing down powerful lines of dialogue or ideas they had as they watched each scene. I also explained that after every scene, we’d discuss it, so if they think of any questions they want to ask the actors about what motivated their characters, what their characters were thinking or feeling in a particular moment, or why the group chose to portray something in a certain way, they would have an opportunity to do so.

I laid out a few ground rules for the performances. My first rule was no accents and don’t use the N-word. I told them, “Although for most of the improvs this would be totally out of place anyway, there are a few improvs where there are confrontations with racist white employers. Although, I encourage you all to get into your characters and act these out, please don’t put on an accent or use the N-word even though it was common with white racists at this time. The point of this lesson is not to develop our acting abilities, but to use these performances to better understand how Reconstruction changed ordinary people’s lives.”

Next, I acknowledged that during the performances there might be a tendency to laugh, but I emphasized, “This isn’t because we’re not taking this history seriously, but because we’re not used to seeing each other perform. So when I say my second rule is to take your performances seriously, I don’t mean no laughing. I mean the goal of these performances should not be to make our classmates laugh, but to learn from the situations we’re improvising. If you take that goal seriously, we’ll all learn more.” This didn’t happen to me at Central, but in the past if I felt like a group was not taking the activity seriously enough, I halted their skit and asked them to rethink their roles and re-perform.

But allowing and expecting laughter is also important. Some of the most joyful moments during this lesson came when my students acted out the scene incredibly well.

But allowing and expecting laughter is also important. Some of the most joyful moments during this lesson came when my students acted out the scene incredibly well. For example, Christine argued, as a freedwoman, with her classmate Peter, in the role of her husband, about sending “their daughter” to the new integrated public school in New Orleans. Christine voiced concerns about whether “their daughter” would be safe from white violence and whether racial tensions in the school would distract her from her education. Peter emphasized how important integrated schools would be to the future of the South. Their argument escalated when Christine exclaimed, “Don’t experiment with my daughter!” Acting angry, Peter responded, “My daughter! That’s the problem! She’s our daughter!” and stomped out of the room — only to return to thunderous applause and laughter.

After I laid out the rules for the performances, I explained the structure we would follow. First, I’d read one of the scenarios. I’d pick a student to proclaim, “Action!” and the improvisation would then begin.

Morgan played a freedwoman who had been hired as a domestic cook. She and the other members of her group had been hired as cooks, but William, their employer, expected them to do all kinds of household chores (cleaning, laundry, etc.). As their scenario explained, “Although these were things they had to do under slavery, many now demand they only be responsible for cooking. This is one of the ways they think freedom should be different from slavery.” After William said, “I’m paying you a good wage to be my cook. What’s the problem?” Morgan responded with fire, “Apparently you don’t know the definition of cook! The only thing we should be cleaning is the dishes. We weren’t hired to do your laundry! You say you’re paying us good wages, but you’re just paying us enough to live. We don’t only need enough to live! We need enough to thrive!”

When they finished their scene, the class gave this group an even louder round of applause than usual and, like we did after every scene, we discussed and drew out the lessons of the scenario we had just watched. I told students the story of our family friend who works as a nanny in South Philadelphia: “Although she was hired to take care of their child, her employers constantly push the boundaries of her job description — asking her to do dishes, fold laundry, etc. — and she frequently has to balance her desire to keep her job with the risk of confronting her employers.” In giving this example, students realized that what these freedwomen engaged in in the 1860s, was radical even by today’s standards. As Alexandra wrote later, “I did not know how so many Black people confronted their employers about wages and working conditions. I thought it was very inspiring because even now people struggle with confronting their employers.”

The post-improvisation discussions are crucial to drawing out the lessons of each performance. I asked the performers to remain “on stage” for the discussion and asked audience members what they learned or questions the improvisation raised for them. Sometimes I invited audience members to ask characters what they thought or felt or if they would have reacted differently than students did in the skit. I also shared with students what really happened and we compared the choices students made to historical reality. In the resources provided with this article (see link at the end of the article), I give detailed teacher notes for each improvisation that will help teachers run successful post-improvisation discussions. In my experience, the quality of the improvisation was not as important as the quality of the discussion that followed it. The improvs took us two 60-minute class periods — six groups performing one improvisation per day.

The following day we debriefed. I asked students to write and reflect on five questions:

• What improv that you watched or performed did you find the most interesting? Why?

• What were some of the actions people took during Reconstruction that reveal Black empowerment?

• How did people resist the return of white supremacy?

• What are examples of how people fought over the meaning of freedom and justice during this time period?

• Which situations/circumstances did you find most moving or powerful? What gives you hope?

In her reflection, Hannah wrote, “Black people protested unfair policies, and unfair treatment. They armed themselves with guns if necessary, and refused to work under racist, unfair conditions. It was powerful to see that Black people weren’t willing to stay quiet. They were going to fight for their rights — no matter what it took.”

Turning Improvisations into Black Power Narratives

Finally, I asked students to take one of the improvs they watched or performed and expand it into a piece of historical fiction. Students won’t know enough to get every historical detail correct; the point is not precise historical accuracy, but to empathize with and imagine in more detail the situations they performed in class. I encouraged them to think about how they would draw out some of the themes we had discussed and we reviewed the elements of a narrative (dialogue, interior monologue, blocking, character and setting description) that we frequently use in my class. Students wrote beautiful, imaginative narratives that brought to life the scenarios. Writing as the cook that Morgan had portrayed in her improv, Dakota wrote:

I took a deep breath before slamming a wooden spoon against the counter. The chattering that was echoing through the kitchen came to a halt as six other pairs of eyes flew to me.

“Aren’t you all tired of doing things you weren’t hired to do?” I demanded. “Isn’t it unfair? We’re workers and if we’re gonna work, we’re gonna work as what we were hired as! I’m not a maid or a slave, I’m a chef and it’s about time he learns that. He can’t ignore all of us,” I said, straightening my back. “I say we march up there and give him a piece of our minds — either he straightens himself out or we leave.”

The other cooks exchanged nervous looks — the thought of “what if?” was probably running through their heads. What ifs are like poison — they’ll kill your dreams and determination faster than anything else, striking you down before you even have the chance to stand.

“We can’t live like this,” I say, pounding the counter again. “We can’t sit here and ask ourselves what if this and what if that because we’ll never get those answers if we don’t act.”

Helen imagined herself as a mother, whose son was sentenced to 40 days in prison for getting in a fight with a white plantation owner’s son:

Black judges and juries can be found in many other communities now. Why did my baby have to end up with a white judge and an all-white jury in our county? . . .

My Adam, my poor baby, was being imprisoned, and not just for a few days, but for 40 goddamn days! “Oh, Judge Meyers, please have mercy on my baby boy. He’s only a child!” I pleaded to the judge in vain. . . .

When we returned home, members of our community came to our house, giving us food and assuring us that everything would be alright. I wanted to believe them, but I couldn’t stand thinking of my boy in jail. After everyone left, the farmworkers stayed back. They wanted to talk about how we could organize to get Adam back. This whole situation with my son was not only about him, but also about the systemic racism that exists in our town. Something needed to be done. . . . Some folks argued that the community should refuse to work for the white planter until Adam was released. . . . After two hours of arguing and yelling, we all agreed that we should protest and strike in order to seek justice for Adam. I was determined to do whatever it took to get Adam released, even if it meant marching around in the scorching sun nonstop every day. No one was going to stop me.

Nicolas captured historian Steven Hahn’s words that Black voting during this time period “required, in essence, a military operation” in his interior monologue about Black men marching to the polls:

We walk with a purpose. Dozens of us march toward the polls to vote Republican. We are aware of the dangers on this path, the hatred of the white-hooded figures, the potential loss of livelihood, the crushing pressure to conform to wants not our own. Yet around me are countless black faces, eyes gleaming with a fire that cannot be quelled. “Is it worth the risk?” I often asked myself. Then I remember my child and I remember when he first opened his eyes. I want him to have the chance to hold the fire of those around me, in his very own eyes. And I want him to pass down this very torch to his children.

Kamea imagined herself arguing with her husband for refusing to wear a badge indicating he voted Republican in the election. Her fictional husband made it clear that he might lose his job if he wore the badge, asking her, “How else am I supposed to provide for you, Ruby? Hold up the household? Put clothes on that boy’s back? A kitchen for you to cook in?” But Kamea’s character stood firm: “You represent both of us. And I don’t care if I gotta carry that baby on my back and get to pulling corn up from them fields. I’d rather be homeless than know that I’m fearing and cowering to them people. I’d rather die than feel like a slave again. We’s freed now, please, please act like it.” She concluded her narrative by imagining her husband, won over to her position, and accepting the consequences for standing up to white supremacy:

“Well, Ruby, I done went and got fired,” he said with a big ol’ prideful smile. I mimicked his facial expression and smiled right along with him, and hugged him real tight too. We’d have it hard looking for a new job for him. But times was always hard and there was one thing they couldn’t take away from us Black folk: our pride. He could have no money at all, but he’d still be rich to me.

My students created moving stories of Black empowerment, imagining themselves into the countless efforts of Black citizens demanding a country that truly provided “liberty and justice for all.”

Found Poem: When Black Lives Mattered

After spending one period writing narratives based on the improvisations, students read their narratives to each other in small groups. These were so powerful that next year, I plan to spend an additional period having students read them out loud in a full class circle.

After students read and gave positive comments to each other in their small groups, we turned to two key texts on the era that give students a broader picture of the social transformation they had written about. Lerone Bennett Jr.’s Black Power U.S.A. and Steven Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet, written almost 40 years apart, both have a chapter titled after James Pike’s observation that the transformations of Reconstruction seemed, to Pike, a “society suddenly turned bottom side up.” I created two short student-friendly readings from those chapters. Both readings are full of metaphors and powerful language that serve as rich soil for cultivating poetry.

I explained to students that they would create found poems from the readings and gave a short presentation on what a found poem is and how to create one. “As we read, we’ll gather words and phrases to use in our poetry,” I explained. “After each reading, we will share words and phrases that stood out to us and create a class list to pull from when writing. Then you’ll rearrange the words and phrases and add words to help your poem flow and give it meaning.”

After we collected words and phrases from the chapter excerpts, we examined a model poem as a mentor text before writing our own. I had a hard time finding a model poem about the Reconstruction era, so instead I used a Langston Hughes poem titled “Good Morning, Revolution” to discuss with students the basics of a poem and how to write poetry about a revolutionary era. Hughes (excerpted here) poignantly sets his theme of revolution in the relationship between a boss and a worker:

Say, listen, Revolution:

You know, the boss where I used to work,

The guy that gimme the air to cut down expenses,

He wrote a long letter to the papers about you:

Said you was a trouble maker, a alien-enemy,

In other words a son-of-a-bitch.

He called up the police

And told ’em to watch out for a guy

Named Revolution.

You see,

The boss knows you’re my friend.

He sees us hangin’ out together.

He knows we’re hungry, and ragged,

And ain’t got a damn thing in this world —

And are gonna do something about it.

We discussed how Hughes used repetition and lists as devices to give the poem rhythm and how he used details about bosses’ and workers’ lives to make his case for revolution. I pointed out the basic mechanics of poetry: stanzas and line breaks. But I also explained that poetry is about playing with language and breaking traditional conventions. I reminded them what we had discussed previously about a found poem — emphasizing that although they pull inspiration and words from the Bennett and Hahn readings, they can feel free to add their own words to shape the poem’s meaning and help it flow.

The poems I got back were a celebration of the revolution of Radical Reconstruction. Hadeel wrote:

It was time for a Real Revolution,

Where we change what seemed impossible to them.

Let us not forget there was a time

Where we worked in gangs under an

Overseer,

where we,

Struggled

and spent sleepless nights

in fear

yet we still rose up.

Stronger than before.

to make a new Brave Black World.

It was time for a Real Revolution.

Finding the key,

To locked doors.

Opening new possibilities,

For this and the next generation.

A generation where no

Boundaries

were set for hope,

And no hope was crushed by

Boundaries.

Una employed lists, drawn from Hahn, to give a concrete sense of the power Black people had acquired:

A Black man occupied virtually every office

available

They were coroners

surveyors

treasurers

tax assessors and collectors

They were jailers

solicitors

registers of deeds

clerks of court

firefighters

election officials

mayors

sheriffs and their deputies.

Stakes were high

When they won,

They passed laws

took care of roads and bridges

controlled budgets

issued warrants

made arrests

controlled weapons and carried out foreclosures

assessed property values

and collected taxes

heard civil and criminal cases,

selected jurors and gave out punishments

created school districts and distributed funds

supervised the voting process.

“Negro rule”

It was “the spectacle of a society suddenly turned bottom side up.”

Johny’s poem was less specific, but used a host of metaphors and imagery, some of his own and many from Hahn and Bennett, to paint a potent picture of the new world Reconstruction created:

In the corpse of the old world,

murdered by liberty and revolution,

a brave Black world emerged.

All barriers crumbled

leaving no boundaries to their hope.

The rulers became the ruled,

and the ruled

the rulers.

In this new Black world,

there was an opening of new possibilities.

The swords of Black pride sharpened,

and the shields of Black power protected,

as the people,

dawning a new sense of self-respect, refusing to give way, give in, or take orders,

took the reins

from the hands

of the old elite.

Presiding over a new era

in the history of man,

reclining in the crimson plush Gothic seats of power

the downtrodden, the disinherited,

with their feet on the rich mahogany tables,

presented their bills

at the bar of history.

More than any other lessons, I think the improvisations, the historical fiction, and the found poem helped students imagine the “new possibilities” that Black people created through struggle during Reconstruction. As my student Irene wrote in her reflection after these lessons, Reconstruction was “a period of mass change that reveals that Black people don’t need saving, but have seized and defined freedom on their own.” And Justin concluded, “Black people were able to turn the tables. It was not only interesting, but inspirational that they were able to make the impossible possible. More people should be aware of what Black people have done for our country and give them their due recognition. Reconstruction teaches us that anything can happen. It teaches us that today, change is possible.”

For the teaching materials related to this article, go to bit.ly/Reconstruction ImprovisationsMaterials.