Teaching to the Heart

Poetry, Climate Change, and Sacred Spaces

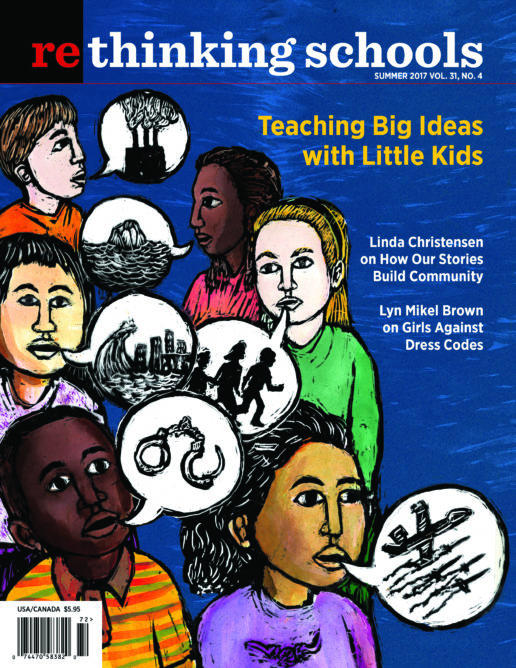

Illustrator: GIFF JOHNSON/AFP/Getty Images

Take a deep breath in.

Hold it for 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Now let it out.

This is what I tell myself as I feel my anxiety start to rise along with the temperature of our tender planet – and this is what I tell my class of 7th graders as we begin our first conversation about climate change. I want my students to understand the very real threat human actions pose to our planet, and I also want to give them tools that will help them be brave – instead of paralyzed – when fear arises. I want them to talk about places that are sacred to them so that they may better understand places that are sacred to others, and better connect with this critical problem we call climate change.

I first discovered Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner in 2014. She had just spoken at the U.N. Climate Change Summit and her poem, “Dear Matafele Peinam,” was going viral online. That summer I attended the Oregon Writing Project, and together with fellow teacher Patricia Montana, developed a lesson using her poem. Jetñil-Kijiner’s powerful piece blended dire reality with unwavering certainty that our actions matter. It was a perfect opening for our first conversation about climate change.

I open by telling my students we are going to start taking a mindfulness minute at the beginning of every class. I have them sit up in their chairs and tell them to have their feet flat on the floor, or at least pointed toward it.

“Put your hands on your desk or on your knees,” I say, “and have your eyes open or closed.” I wait until they are ready, gently coaching students with a gesture or smile to sit up a little straighter, or put their head down on their desk if the temptation to look around is too great.

“OK,” I say. “If this is the first time you’ve done this, it may feel a little weird at first, but just trust me, I got you.” A few of the boys giggle, but they stop, and I begin.

“I want you to think about your toes. Go ahead and wiggle them in your shoes. Notice where your feet touch the ground and what your sock feels like on your foot. Now think about your ankles. We don’t think about our ankles much, do we?” I pause for just a beat. I don’t want to rush our body scan exercise, but I also know that with middle school students, one minute is about all I have the first time around. So I keep talking, my voice slow and serene, and ask them to think about their stomachs, their hearts, where their backs hit the chair and where it’s just air. I finish by asking them to think about the space just above their heads and to take a big, deep breath that we hold for five counts before letting out.

I look at my classroom of 12- and 13-year-old students. Some are squirming in their seats, some haven’t lifted their heads from their desks, and one or two are calmly opening their eyes.

“I’ll bet you are wondering why we did that,” I say, while preparing the video of “Dear Matafele Peinam” on my computer. “We did the mindfulness minute because I want you to notice how you are feeling, right now. In a minute, I’m going to play this video and I will ask you to notice how you feel after watching it.”

I pass out copies of the poem and continue explaining.

“We are going to watch a poem written by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner. She’s from the Marshall Islands and she’s a climate change activist. She dedicated her poem, ‘Dear Matafele Peinam,’ to her 1-month-old baby. Matafele Peinam is the baby’s name and Ms. Jetñil-Kijiner chose that name because it is the name of the two places where she and her husband grew up. While you are watching, I want you to think about what you are feeling. Like, there’s one line that no matter how many times I watch the video, makes the hairs on my arm raise up, and I feel kind of excited, and hopeful, and maybe a little scared. When you see a line that makes you feel angry, or sad, or anything like that, I want you to star it on your paper, and maybe make a little note about how you are feeling.”

I hit play and move to the back of the room. Within seconds, students are transfixed, eyes glued to images of sweet Matafele Peinam, of oceans eating shorelines, activists raising fists and marching in the streets. A few students remember to star their favorite lines, but I offer to play the video again so that the rest of the class can take notes. (I find students always say yes to this offer.)

After rewatching, Mike shouts out, “A 10! I give that poem a 10!” The rest of the students start buzzing, and impromptu conversations bubble up among tablemates. I let the conversations flow for a few minutes.

“OK, class!” I say, getting us back to the poem, “Share with your group. Tell them which lines you starred and why.” I let them talk a bit, and then call for their attention. “Now I want us to talk as a whole class about the lines that evoked emotion for you.”

Cameron, Athena, and Melody come to the front of the room where I have a T-chart hanging. On the left side of the T-chart, the column says “Line” and on the right side it says “How it made us feel.” I model the task for my students. “Everybody see this line here? The one that says ‘Still they see us’? I’m going to write that line on the left side of this chart and then on the right I’ll write ‘Excited, hopeful, hairs stand up on my arm’ because that’s what I feel when Jetñil-Kijiner reads that line.”

Cameron starts calling on other students, and Athena and Melody each take charge of the writing for the T-chart. I stand at the back of the classroom and watch my kids run the show. “I like the line ‘No greedy whale of a company.’ It makes me feel angry,” Alejandro says.

“And where do you feel that in your body?” Cameron asks, without any prompting from me.

“In my heart,” Alejandro replies.

Nicole raises her hand. “I really liked the line ‘No one’s losing their homeland,’ and I don’t know why but I kinda felt that in my throat. It made me feel sad. I don’t know why but this whole poem made me feel sad.” Athena and Melody add the line to our chart and write “throat” and “sad” next to it. Then Cameron calls on Elisa.

“This one is kind of weird but I really liked it, ‘You are bald as an egg and bald as the buddha,'” and the class chuckles.

“Oh yeah,” Ander says, “I really liked that one also.”

Elisa continues, “I like that line because it made me laugh, and the poem is kind of sad so I liked that line because it was a balance to the sadness. I felt it in my heart.” After students amass a list that is longer than can fit on the poster, I ask them to look at their poems again.

“I want you to use a highlighter and find places in the poem where Jetñil-Kijiner uses repetition. Work with your groups for about five minutes, and then we will share with the whole class.”

Ander calls out, “Does it matter what color highlighter we use?”

“Not really,” I respond. “In a minute color will matter, but right now just make sure you use the same color highlighter for all the examples of repetition.”

Students quickly reach for their favorite color highlighters and bend their heads over their poem. After about five minutes I call them back to attention and we make another poster listing all the repetition. Students easily pick out the “we are’s” and “no one’s” and “they say” that form the bones, or the framework, of the poem.

“So the last list we are going to make is about personification. Does anyone know what personification means?” I ask, as I pull out the third and final poster we will make that day. I write “Personification” at the top, and then turn around to see if anyone can answer the question.

Maya has her hand up. “I think we learned about that last year in Mr. Verbon’s class. Isn’t it when you make things act like people?”

“Yes! That’s exactly it!” I write Maya’s definition underneath the word “personification.” “I want you to find examples of personification and highlight them. Use a different color highlighter than you used when you were highlighting repetition. Look for examples of oceans and trees and companies doing things like humans do, and highlight them. Then share with your group.”

The class gets started and I walk over to Nafeesa and Huan, both English language learners who I thought might need some support with the activity. I draw a bracket around a short stanza that contains an example of personification. “Nafeesa, Huan, can you find some personification in this part? Where is a thing, like an ocean or a tree, doing something that a human normally does?” Nafeesa hesitates, then points to the words “lagoon” and “chew.”

“Great!” I say. “Highlight that one, and you can share it with the class.”

Again we make a poster and list all of the examples of personification in the poem. Sometimes students will suggest lines that are not personification, and in that case I ask them to look at our definition and talk about whether their example matches it.

By this point it’s time to get students thinking about their own sacred spaces. “Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner wrote this poem about the Marshall Islands because it is one of her sacred spaces: It is very special to her. What are the places and spaces that are sacred to you? I want you to open your journals and go to a new page. Write ‘Sacred Spaces’ at the top. I’m going to put the timer on and for two minutes we are going to write a list of as many places that are special to us as we can think of.”

I set the timer and write a few ideas of my own down before checking on Nafeesa. Nafeesa sits at a table with Maya, Daisy, and Eleanor. She is from Sudan and has been at our school about a year. Her list is blank, so I ask a few questions to get her started. “Nafeesa, what places are special to you? Where do you go every day that you like?”

“My house,” Nafeesa replies.

“Great! Write that down. Girls,” I say, looking at the other three, “What about your houses? Are they special to you too?” Eleanor and Maya nod their heads, and Daisy wrinkles her nose. “OK, so Eleanor and Maya, steal Nafeesa’s idea! Add it to your list. In a minute, the whole class is going to share with their groups, but I want you girls to get a head start. Work as a team, ask each other questions, and make sure that everyone has at least four or five places on their lists.”

As I walk away to check on Huan’s group and give a similar spiel, I hear Eleanor asking Nafeesa, “What about in Sudan? Do you have any special places in Sudan?”

When the timer goes off I call out to students, “OK, share your lists with the people at your table! If something on someone else’s list reminds you of another place, write it down. If you like the same place as someone else on your list, write that down! Stealing is completely legal right now!”

After a few minutes, I tell students to star the top three places on their list. From there they have to narrow it down to one. “You can switch and write about another place later, but for now just choose one. We are going to practice personification.”

Many of my 7th graders have “my room” on their lists, so we start with that. Eventually, I will want students to write about a sacred space that is affected by climate change, but for now I want them to forge an emotional connection to their writing so I let go of controlling what they write about.

“OK, so lots of you have your rooms on your lists. David, can you tell me one object in your room, please?”

“Um, my Pokémon cards?” David says, hesitantly.

“Great! Now, help me paint a picture in my mind. Where are your Pokémon cards?”

“On the table by my bed. Under the lamp,” he says.

“OK, so class, let’s personify David’s Pokémon cards. What could they do that humans do?” This question puzzles students a bit, but with a little time to think, hands start shooting up.

“They could be standing to attention,” Maya suggests.

“Yes! They could be stacked in a pile and standing to attention,” I write down.

“Maybe they could bask in the light of the lamp?” Cameron asks.

“Perfect!” I write it down.

“Maybe they are waiting patiently for me to come home and play,” David offers.

“Great – you all have the idea. Now, I want you to choose an object from your own sacred space and play around with personifying it. If someone at your table gets stuck, help them get unstuck.”

This is the hardest part, and lots of students don’t get personification right away, but who gets anything perfect on the first try? A few times when I have taught this lesson, I’ve taken students out to the water garden and had them make lists of what they see, hear, and feel. Then we go back to the classroom and practice personifying what we just experienced in the water garden, like making the sun dance with the shadows and the breeze kiss our cheeks.

After students have listed their own sacred spaces, and tried their hands at writing a few lines of personification, it’s time to get them started on their own poems. I hand out copies of the poem I wrote while developing this lesson.

“My poem is not about climate change, it’s about gentrification. I wrote it thinking about a former student of mine, his neighborhood in North Portland, and the school I taught at. While we read this poem, I want you to think about what is different between my poem and Jetil-Kijiner’s, and what is the same.”

We start reading the poem, read-a-round style with the first student reading the first line, the second student reading the second line, and so on.

dear nicholas marshall,

you are one million tender stories

scattered across an inky black skyyou are graffiti letters, firing across the canvas

you are a careful warrior

sidestepping landmines in the halls of our school . . .

“OK, so what is different?” I ask.

“You write about different things,” Erik says.

“Your poem is shorter,” Gus notices.

“And what’s the same?”

“You both write your poem to a person,” Nicole says.

“You use personification,” Maya says.

“Yes! You all are really good at noticing these differences. I have to tell you, this poem was really hard for me to write. I spent at least eight hours and did multiple drafts until I got it to a place that I liked. What really worked for me was to take all of Jetil-Kijiner’s repeating lines – you are, they say, no one’s gonna, etc. – and use them like headings for a list. So when I wrote “dear nicholas marshall,” and then wrote “you are,” I had a list of about 10 options that I could use to complete that line. Make sense?”

I pull out another sheet of poster paper. “But my way is just one way you can dive into the writing. Tell me, how do you all get started writing?” On the top of the poster I write “How to Dive into Writing” and start calling on students.

“I like to close my eyes and picture the scene in my mind,” Eleanor says. She calls on the next person, Cali.

“I like to draw a picture of the place,” Cali says. “Ander,” she adds, calling on the next student.

“I just start writing,” Ander says with a shrug of his shoulders.

At this point, there are only 15 minutes left of class and I tell students that we are going to use the rest of our time to dive into our writing. I put on the Classical Goes Pop Pandora radio station, remind students that for the first 10 minutes of writing time we keep our voice levels at zero, and off we go.

I check in on Marcus, who’s having a particularly hard time getting started.

“Marcus, what’s going on? How’s the writing coming?”

Marcus shrugs, “Not so good.” Then he says, “I don’t mean to be rude but they’re not going to make a difference. Those protesters in that video, I mean, I’m saying that the companies, well, they are not going to pay attention to them.”

I take a deep breath. I am not sure what I am going to say – Marcus’ fears and cynicism mirror my own.

“I hear you, Marcus. I’m really glad you brought this up – it’s an important point and I feel that way lots of times too. But you know, we didn’t always have a 40-hour workweek. In the past, employers could make people work much more than that, but then people got together and protested and made a difference. And women, we couldn’t vote until 1920 – how do you think that all changed?” I paused and took another breath. “I know what you mean though. Sometimes I look at all the people marching and I think, ‘It’s not enough. It’s not going to be enough.’ But the thing is, I could live my life thinking that nothing I do matters, or I could live my life as if everything I do matters.” I stop talking and look at Marcus’ wide-eyed face. Was that the right thing to say?

“OK, OK, Ms. Nicola, I got you. That makes sense.”

“I don’t have all the answers, Marcus, that’s why we need each other to help us figure it out. I can, however, help you get a poem started, if that’s what you want,” I say, flashing him a grin.

“Naw, that’s OK, Ms. Nicola. I think I have some ideas now.”

Fiona chooses to write about gentrification and writes about Hawthorne Street, naming the “beautiful old shops and restaurants . . . that each held a story about their history.” She contrasts this with Hawthorne Street today with “the rat-a-tat-tat of jackhammers grinding away at the sidewalk,” and the “condos, the looming buildings shading out all the sun that once shined bright on us.”

Elisa writes about Squam Lake, a place that stands at the center of her childhood memories. It was her grandparents’ sacred space, and her mother’s, and now hers.

Dear Squam Lake,

You are the fresh foggy mornings and the cold dewy grass on my bare feet.

The smell of the old barn,

and the swaying waves in my mind telling me to come back to the water for just one more swim to rinse all my troubles away.

David chooses to write about his basement, how it’s “cold as snow” and it “locks out the babbling trees.” His poem doesn’t feel done, and so I ask him what else he could say about his basement. Why is that his sacred space? Finally, he decided to end with “every day you make me climb the endless stairs to the never ending journey.”

After five days, I tell my students that, like it or not, we need to come to a stopping point. “Writing is never done,” I proclaim. “But we can come to a point where we have something we are proud of.” We circle up and students take turns reading their poems for the class. After each person reads, the rest of us write them a compliment, or praise paper. I keep a bucket of small squares of scratch paper I hand out any time we share our writing. Students know that they need to write their names, the person’s name who is reading their poem, and then either a line they really liked from the poem, or something it made us feel. In the last five minutes of class we exchange praise papers so that each student leaves with at least 20 different comments of praise about their work.

These days, we teachers cannot afford to deliver the same “save the planet” lessons of years past. When I was a middle school student, I learned to recycle, and I learned to fear the great hole in the ozone that existed uncountable miles away from my Portland home, and affected polar bears I never saw in the wild. I did not see myself as connected or empowered to change the existing system. When my students identified the emotions that came up when listening to Jetil-Kijiner’s work or their peers’ work, they started to understand what it means to have a sacred space, and what it means to feel connected to that place. When they practiced one-minute mindfulness, they learned how to breathe into that emotional connection, and not become paralyzed or fearful of it. As this unit continues, I plan to ask students to make connections between their personal sacred places and places in the world that are being affected by climate change. They will use what they’ve learned to write a second set of poems that honor these places that are at risk.

Jetil-Kijiner’s work offers a blueprint for climate change activism, but it isn’t until we allow students to voice their concerns about their own sacred spaces that real change can take place. Real change requires teaching to the heart. Its pace is slow, but it is certain and steady, and for my students, their “Dear Matafele Peinam” poems were a powerful way to start.

Read the poems “Dear Matafele Peinam” by Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and “Dear Squam Lake” by Elisa Garcia Mead below.

Dear Matafele Peinam

By Kathy Jetil-Kijiner

Dear Matafele Peinam,

You are a seven month old sunrise of gummy smiles

you are bald as an egg and bald as the buddha

you are thighs that are thunder

shrieks that are lightning

so excited for bananas, hugs and

our morning walks past the lagoon

Dear Matafele Peinam,

I want to tell you about that lagoon

that lucid, sleepy lagoon

lounging against the sunrise

Men say that one day

that lagoon will devour you

They say it will gnaw at the shoreline

chew at the roots of your breadfruit trees

gulp down rows of your seawalls

and crunch your island’s shattered bones

They say you, your daughter

and your granddaughter, too

will wander

rootless

with only

a passport

to call home

Dear Matafele Peinam,

Don’t cry

mommy promises you

no one

will come and devour you

no greedy whale of a company sharking through political seas

no backwater bullying of businesses with broken morals

no blindfolded bureaucracies gonna push

this mother ocean over

the edge

no one’s drowning, baby

no one’s moving

no one’s losing

their homeland

no one’s gonna become

a climate change refugee

or should i say

no one else

to the Carteret Islanders of Papua New Guinea

and to the Taro Islanders of the Solomon Islands

I take this moment

to apologize to you

we are drawing the line

here

Because baby we are going to fight

your mommy daddy

bubu jimma your country and president too

we will all fight

and even though there are those

hidden behind platinum titles

who like to pretend

that we don’t exist

that the Marshall Islands

Tuvalu

Kiribati

Maldives

Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines

floods of Pakistan, Algeria, Colombia

and all the hurricanes, earthquakes, and tidalwaves

didn’t exist

still

there are those

who see us

hands reaching out

fists raising up

banners unfurling

megaphones booming

and we are

canoes blocking coal ships

the radiance of solar villages

the rich clean soil of the farmer’s past

petitions blooming from teenage fingertips

families biking, recycling, reusing,

engineers dreaming, designing, building,

artists painting, dancing, writing,

and we are spreading the word

and there are thousands

out on the street

marching with signs

hand in hand

chanting for change NOW

and they’re marching for you, baby

they’re marching for us

because we deserve

to do more

than just

survive

we deserve

to thrive

Dear Matafele Peinam,

you are eyes heavy

with drowsy weight

so just close those eyes, baby

and sleep in peace

because we won’t let you down

you’ll see

_

Dear Squam Lake

By Elisa Garcia Mead

Dear Squam Lake,

You are the fresh foggy mornings and the cold dewy grass on my bare feet.

The smell of the old barn,

and the swaying waves in my mind telling me to come back to the water for just one more swim to rinse all my troubles away.

You are the French Moustaki music I hear from my grandmother’s kitchen while she makes the yummiest heartfelt meals.

And the joyful laughter I hear from my cousins as we jump over piles of dog turd.

Dear Squam Lake,

Where are you?

Do you remember me?

I remember you.

I remember that island, the one where we sang beautiful hymns and prayers.

The one where we washed all our sins away.

The one my Oma and Opa, Bammy, and Mama love so dearly?

The one with the rusty old docks and loud organs playing.

Well, they say one day the water itself will swallow it down into its empty core and leave no trace of sand behind.

Well, I also remember this tiny wooden house.

The one that held so many memories and lost spirits from generations before.

The one that me, my cousins, my Mother, and even all of her cousins all grew up in.

They say that one day, its bones will shatter into one million pieces and collapse onto the ground.

They say the wind will shove it down and have the weeds rise up until you can no longer see its precious limbs.

They say you, beautiful Squam, will dry up into a wrinkly old desert. No more jumping into that liberating water or taking long walks on the beach. No more capsizing “ships” or taking artsy pictures with my best friends. No more dancing on rocks, no more climbing trees, no more running across the long fields, no more eating ice cream in the cold, no more doing backflips off boats.

No.

Dear Squam Lake,

You are my childhood, past, present and future. And I will NOT take you for granted. Instead, I’m turning those No’s into Yeses and those Don’ts into Do’s. Those dreams into plans because it’s time to take this into my own hands. Because Squam Lake, I’m not letting you down. Not now, not ever.