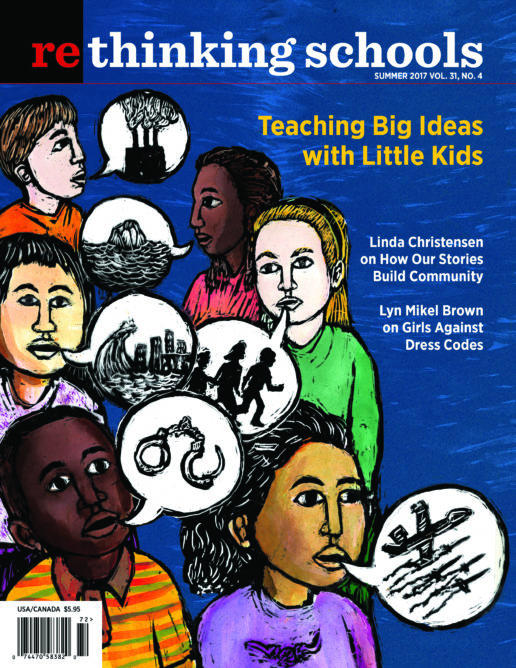

Preview of Article:

Love for Syria

Tackling World Crises with Small Children

Illustrator: Molly Crabapple

It was a typical Monday morning in my 1st- and 2nd-grade classroom. The students entered, greeted their friends, and chose a morning work activity.

After everyone settled in, Sarat chose “Watch Me (Whip/Nae Nae)” for the clean-up song and the students danced while cleaning before we circled up for our morning meeting. We had been learning how to greet one another in many different languages, so the students each chose a different language and said hello to their neighbors in Bengali, Japanese, Swahili, Arabic, Spanish, and other tongues. Then we moved onto sharing. The topic was simple and one of our favorites: “How are you feeling today?”

“I’m feeling nervous,” said Grace, who shared that her parent was going in for surgery that morning.

“I’m happy to be at school and see my friends,” exclaimed Willow, smiling brightly.

Next, it was our student teacher Ruqayya’s turn. “I’m feeling sad,” she said. “Is it OK if I share about it?”

The children nodded enthusiastically. I, too, was curious to hear what was concerning my friend and colleague.

“I was listening to the radio on my way to school,” she said. “I am not sure if many of you know, but there is a war going on in a country that is near my home, in a place called Syria.” The children’s eyes grew wide and they leaned in closer. War wasn’t something we had talked about in our classroom and it seemed to make them a little nervous.

“They were interviewing children who had to leave their homes because of war and were asking them how they were feeling,” said Ruqayya, who identifies as a Palestinian refugee.

“One of the children was saying they wanted some paper and a crayon. Just one crayon so they could write and draw to help themselves feel better. It made me so sad and made me think about all of the things we have in our classroom that we should feel grateful for. I can’t stop thinking about it.”

At this point, a tear fell down Ruqayya’s cheek. Willow asked Ruqayya if she would like a hug. Harper grabbed a tissue and the other kids gathered close to comfort her. I sat back in awe of this organic moment. And then, like so often happens in classrooms, it was time to transition for math.

I thanked the class for taking such good care of one another and let them know we could revisit this important topic soon.