“Human Beings! Human Beings!” An Open Letter to Educators on the Dangers of AI

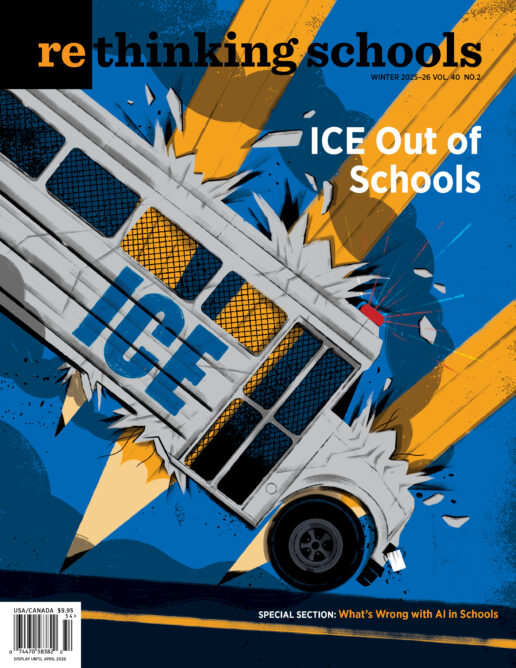

Illustrator: Boris Séméniako

The film shows an ambulance bombed on its way to save a child who is talking to an emergency dispatcher; she is the only person left alive after her family’s car was fired on by Israeli commandos in Gaza; then the child too is killed.

A shaky camera shows a young man kidnapped by masked agents in his home in New York City as his pregnant partner’s voice cracks pleading into the phone, “They just, like, took him! I don’t know what to do. What should I do? I don’t know!”

The photo shows the secretary of Homeland Security reveling in the torture of immigrants as she poses in front of dozens of half-naked men held captive in a prison in El Salvador.

Dizzying. Disorienting. Debilitating. If you sometimes feel the impulse to scroll quickly by, to swipe to a different reality where such things are impossible, me too. There is a childlike part of myself that wants to believe that when I close the app, the starvation in Gaza ends; that when I go on do not disturb, the labor organizer in Washington State is no longer locked up in the ICE detention center in Tacoma.

Perhaps that is why I am so moved by the Freedom Flotilla’s unceasing efforts to deliver aid to Gaza, the residents of Chicago blowing on their whistles to alert their neighbors when ICE is near, and the parents in my own city who are organizing morning and afternoon street patrols to make sure immigrant students and families feel safer coming to school. These actions ground me. They are reminders that fascism is doing its brutal and bloody work in places, in locations, in the physical world, that reality is, well, real. And we can confront it where it happens, as it happens, not through our phones, but with our bodies, our hearts, our minds, our humanity.

In this time of ascendant authoritarianism, we need to be careful not to outsource any more of our humanity to tech billionaires. OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Microsoft’s Copilot (among others) are flooding our inboxes, search engines, and social media platforms with seductive promises — and more and more, so-called leaders in education are taking the bait. But if we are committed to defeating fascism, and to building a livable future for ourselves and our students, we must take a fulsome, deliberative pause before accepting “AI” as inevitable.

01

Look, I get it.

I have almost 200 students. I teach several preps. I get one 50-minute planning period that doesn’t even scratch the surface of my piles of student work, copies to be made, IEP meetings to attend, emails to be answered. I often do not have sufficient time to create or find good curriculum; I often do not have sufficient time to level readings for my many-abilitied and multilingual students; I never have sufficient time to write my yearly so-called SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, time-based) goals at the absolute busiest part of the year; and my teaching partner and I definitely did not have time to write and send that letter home to caretakers about that film that we’re planning to show this week, which we forgot to do yesterday, and if we do not get it out today, it will be too late.

This job is structurally impossible. And a colleague has shown me how easy it is to level readings on MagicSchool; ChatGPT spit out a pretty good rough draft of that parent letter we needed; and would my admin even have noticed or cared if my goals were co-“written” by Claude?

But like Hansel and Gretel enticed into the witch’s house by the irresistible scent of baking cookies and bread, we are in danger. What if the architects of these creepy machines are luring us into their future with promises of an easier job only to throw us into the oven and serve us up to the billionaire class for lunch?

02

Two decades of teaching U.S. history is what anchors much of my thinking and analysis. Years ago, for a teaching activity, I gathered a bunch of quotes from several histories of the U.S. war in Vietnam, all of which provided information to students on why the United States was defeated in its mission to create an anticommunist state. Several of the quotes were from Vo Nguyen Giap, the Viet Minh general who is often cited as one of the most brilliant military tacticians and strategists of the 20th century. Here is the Giap quote that rings in my head right now:

We were waging a people’s war . . . in which every man, every woman, every unit, big or small, is sustained by a mobilized population. So America’s sophisticated weapons, electronic devices, and the rest were to no avail. . . . In war there are two factors — human beings and weapons. Ultimately, though, human beings are the decisive factor. Human beings! Human beings!

I worry that the “AI” peddlers want us to forget that we are human beings, teaching human beings, in a community of other human beings.

03

Teacher friends, did you read Paulo Freire when you were in school? Is he a touchstone for you too? I think I wrote a whole essay when I was 22 on his famous line from Pedagogy of the Oppressed, “Reading the world always precedes reading the word, and reading the word implies continually reading the world.” I see my task as a teacher to equip students to read the word (develop the intellectual skills to decipher and express knowledge) and the world (develop a social and political analysis that explains why things are as they are). The promise of the classroom is that the alchemic relationship between word and world will cultivate in our students a sense of agency and the skills to align their actions to their ideological commitments. In other words, I try to ready kids to fight for the world they want.

Can we achieve this most critical task if we outsource our own reading of the word and world to ChatGPT?

04

When all those years ago, I went through the time-consuming process of reading books on U.S. policy in Vietnam to gather quotes for a lesson in which groups of students digested the quotes together to identify themes and patterns, and ultimately used the primary and secondary sources to answer the question “So why did the United States lose the war?,” I was consciously rejecting the dominant approach to history teaching.

Instead, I could have turned to my school’s adopted textbook, and state social studies standards. There, my students — and I — would have encountered what Toni Morrison and others call the “master narrative” of the Vietnam War. According to Morrison, “The master narrative is whatever ideological script that is being imposed by the people in authority on everybody else.” Traditional textbooks — anonymous, content-by-committee, voice-of-God affairs — are ridden with master narratives that obscure both the bloody and destructive history of colonialism, capitalism, nationalism, and racism, and the powerful, sometimes successful, grassroots movements of people who have never stopped fighting for a different future. Master narratives, as the name suggests, are the mythologies elites use to justify their own domination. When we refuse standardized curricula that regurgitate these lies, we take away a powerful tool from the fascist toolbox.

Now we are encouraged to reach not for textbooks, but for “AI.” Will these tools deliver us from the old master narratives?

05

Colleagues, you may have noticed that I have avoided talking about the actual technology. Maybe you, as I did, feel intimidated by all the talk of “AI;” the tech billionaires and their media apparatus make it seem terribly scientific and complicated. So before I endeavored to write this letter, I decided to study. I read several books, dozens of articles, listened to countless podcasts. And I’ve got to tell you, the “tools” being rolled out as “AI” in our schools basically amount to a super-duper, hypercharged, really snazzy autocomplete. That’s right, just like when you’re texting on your phone to your sweetheart, “Running . . .” and the messages app suggests the next word you want is “late.”

These automated purveyors of “intelligence” scooped up as much human-created stuff (books, blogs, speeches, articles, encyclopedias, posts, videos, songs, poetry, paintings, cartoons, stand-up routines, etc.) off the internet (often without permission from authors and artists) as they could. This is the so-called “training data.” What are the machines trained to do? Predict the next word in a chain of words based on the probabilities rendered by all that data and a corporate-designed algorithm. After you prompt a chatbot like ChatGPT, it is not “answering” you; it is spitting back a prediction based on the trillions of sources its algorithm has digested. AI hype people will tell you that what makes these tools so spectacular is the breadth of the dataset — “the entire corpus of humanity!”

There are several astounding pages in Karen Hao’s book, Empire of AI, in which she describes how OpenAI assembled the datasets that trained the different iterations of ChatGPT. She explains, “To get the best performance, the size of the dataset needed to grow proportionally with the number or parameters and amount of compute” (134). At first, they were selective about what got poured in: only “the text from articles and websites that had been shared on Reddit and received at least three upvotes” (135). But that wasn’t enough. Next they poured in

English-language Wikipedia and a mysterious dataset called Books2, details of which OpenAI has never disclosed. . . . This was still not enough data. So Nest [a team at OpenAI] turned finally to a publicly available dataset known as Common Crawl, a sprawling data dump with petabytes, or millions of gigabytes, of text, regularly scraped from all over the web — a source Radford [one of the architects of ChatGPT] had purposely avoided because it was such poor quality. . . .

When it came time to assemble the data for GPT-4, released two years later, the pressure for quantity eroded quality even further. . . . OpenAI employees gathered whatever they could find on the internet, scraping links shared on Twitter, transcribing YouTube videos, and cobbling together a long tail of other content, including from niche blogs, existing online data dumps, and a text storage site called Pastebin. Anything that didn’t have explicit warning against scraping was treated as available for the taking (136).

So not the “entire corpus of humanity.” Instead, a deeply limited dataset, based on a chaotic, voracious scrape of the internet, an internet shaped by the same forces of domination that have always restricted who gets published and who gets the mic.

06

One major contribution feminism — and particularly Black feminism — made to my learning was to help me understand that what elites and oppressors tell you is “human nature” or “universal” or “natural” or “normal” or “intelligence” is almost always exactly the opposite: oppressive ideologies policing, marginalizing, excluding, and erasing the actual “corpus of humanity” and all the variety and multiplicity it entails.

I don’t want us to forget that the predictive algorithms being marketed as “intelligence” were built out of an internet riven with white supremacy, sexism, and colonialism, and fueled by capitalism.

Emily Bender and Timnit Gebru have written that “large datasets based on texts from the Internet overrepresent hegemonic viewpoints and encode biases potentially damaging to marginalized populations.” That was from the article — “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” — that got Gebru, a Black woman, fired from her job working on AI ethics at Google.

07

Feminists taught us that the category of “universal man” is violent and hides the harm it does. Is “AI” becoming one of those universalizing categories that similarly denies not only its own biases but also its material footprint, its social and environmental impacts?

Some things I have learned about chatbots that I want to share with you:

- To train and run the chatbots, the tech companies build data centers. According to Karen Hao, researchers once used football fields as the illustrative metric, but now those are far too small. “Their data centers are ‘campuses’ — large tracts of land that rival the largest Ivy League universities, with several massive buildings densely packed with racks of computers.”

- The Southern Environmental Law Center has found that one of Elon Musk’s data centers (which supports his social media platform’s chatbot Grok) in Memphis is illegally using gas-powered turbines that pollute the air with between 1,200 and 2,000 tons of smog-forming nitrogen oxides per year, as well as exceeding critical limits on hazardous air pollutants like formaldehyde.

- The data centers use enormous amounts of energy, which require huge cooling systems — which require even more energy and potable water (so as not to clog pipes or grow bacteria that could harm hardware).

- According to Emily Bender and Alex Hanna, “The ‘AI Overviews’ feature that Google added to search results in 2024 likely consumes 30 times more energy per query than just returning links.”

- Hao writes, “According to an estimate from researchers at the University of California, Riverside, surging AI demand could consume 1.1 trillion to 1.7 trillion gallons of fresh water globally by 2027, or half the water annually consumed in the U.K.”

- The data centers are filled with exceptionally powerful computers whose manufacture uses large amounts of copper, lithium, and rare earth elements — which has created a “critical minerals race” for the scarce resources that are mostly extracted from the Global South.

- Behind “artificial intelligence” is a whole lot of human, often exploited labor. The undifferentiated swamp of words, images, and videos that are used to train chatbots include large troughs of horrible stuff. Since the dataset is too large to manually sort through, other AIs are built to do content moderation of the AI. But to train that AI, humans are required. This process is called reinforcement learning from human feedback. According to journalist Billy Perrigo, “The premise was simple: feed an AI with labeled examples of violence, hate speech, and sexual abuse, and that tool could learn to detect those forms of toxicity in the wild.” But Perrigo found that OpenAI’s data labeling work was being outsourced to workers in Kenya being paid less than $2 an hour to spend all day looking at monstrously upsetting material: child sexual abuse, bestiality, murder, suicide, torture, self-harm, and incest.

If we are considering incorporating chatbots into our professional lives, I want us to remember, the “intelligence” may be artificial, but the data centers, minerals, water, and human beings that make it all run are real. And the big players behind “AI” — Meta, OpenAI, Microsoft — seem to be following an old and toxic capitalist playbook: extraction, exploitation, environmental destruction.

08

Comrades, what if AI in schools is a wolf — or, more precisely, austerity — in sheep’s clothing? As Bender and Hanna have written, “AI hype at work is designed to hide the moves employers make toward the degradation of jobs and the workplaces behind the shiny claims of techno-optimism.”

Witness this AI hype in action: Last week I received an email from Varsity Tutors reminding me,

You also now have access to our AI Teacher Tools, including AI Lesson Plan Generator and AI Generated Practice Problems. We are getting feedback from your peers that these tools are saving teachers 7–10 hours per week.

The week before it was a Google Classroom promotion that suggested I should consider “Teacher-led Gems:”

Educators can create Gems, which are custom versions of Gemini, for students to interact with. After educators select Classroom resources to inform the Gem, they can quickly create AI experts to help students who need extra support or want to go deeper in their learning.

And last year, Alberto Carvalho, superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District, poured $6 million into an AI-for-schools chatbot, stating it would “democratize” and “transform education.”

Meanwhile, what was United Teachers Los Angeles — the LA teachers’ union — fighting for? Salary increases that would make housing and health care affordable, decreased class sizes, more school nurses, psychologists, counselors, more support for special education students and staff. Exactly none of these demands can be addressed by more technology; all of them require more funding and more human beings.

AI will be encouraged as a time-saver to help us with our inbox. (So our prep periods can be shortened.)

AI will be offered as professional development to help us write curriculum. (So our planning time can be cut.)

AI will be suggested as a teaching assistant to help us grade papers. (So our class loads can be increased.)

AI will be celebrated as our “co-pilot” to help answer students’ questions. (So anyone can do our job.)

No. Rather than accept this “help” that will de-skill, degrade, and devalue us, we need to organize — like UTLA — for the conditions that make real teaching and learning possible and joyful, with human beings at the center.

Human beings! Human beings!

09

I want to return for a moment to my humble Vietnam lesson. An AI booster might ask, “But isn’t that exactly the kind of lesson AI could help with?” Couldn’t I have saved a heap of time by prompting a chatbot to spit out a large selection of quotes and then selected the best ones for my activity?

I will allow that yes, ChatGPT, with the right recipe of prompting, could likely produce a similar selection of quotes. But could is different from should.

Maybe you know of or have read the historian and thinker Robin D. G. Kelley? In his beautiful book Freedom Dreams, he wrote, “Making a revolution is not a series of clever maneuvers and tactics, but a process that can and must transform us.” I think that is also true of curriculum development. It is not a series of clever tricks that we can outsource to a machine with a focus only on the end product. It is a process capable of transforming us.

In letting a machine generate my curriculum, I would have robbed myself of the experience of inquiry, learning, revelation, and the incitement of new curiosities. I expect you know what that feels like. For many of us, I am sure, that feeling is at least a part of what moved us to become teachers.

Freire again: “For apart from inquiry, apart from the praxis, individuals cannot be truly human. Knowledge emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.”

Human beings! Human beings!

10

Teacher comrades, fascism is here. And my question for us is this: Are the chatbots being marketed to us as “intelligence” going to help us combat it?

Not only will they not help, they are designed to mask the realities we must face, fight, block, and build alternatives to. Let’s not let the AI con disappear and devalue our labor, art, expertise — and, most importantly, our vision of the world we are fighting for.

We are human teachers. We foster human communities with our students in the sacred human space of a classroom. We build curriculum with our human comrades and colleagues by reading together and talking about human-created art, literature, history, music, science, and culture. We experiment with and workshop new pedagogies and lessons with each other at conferences and in classrooms, community centers, and union halls. We read our human students’ writing and learn about their lives and talents and hopes and fears and visions of a just future; and we witness their courage as they share in shaky voices some of their writing in the community circle, and their compassion as they listen to each other with care and attention.

This teaching is not fancy, but it is antifascist. It creates social connection rather than division; it affirms the value and capabilities of human beings; and it grows from the premise that together we can build a better future for all of us.

Teachers, I know there are many powerful forces beckoning us toward AI. What if we said, “No thanks” and turned instead to each other, one human being to another?

Solidarity,

Ursula