“I Really Felt Like I Was Using My Writing for Good”

Student Writing on Redlining, Urban Renewal, and Gentrification — The Definition Essay

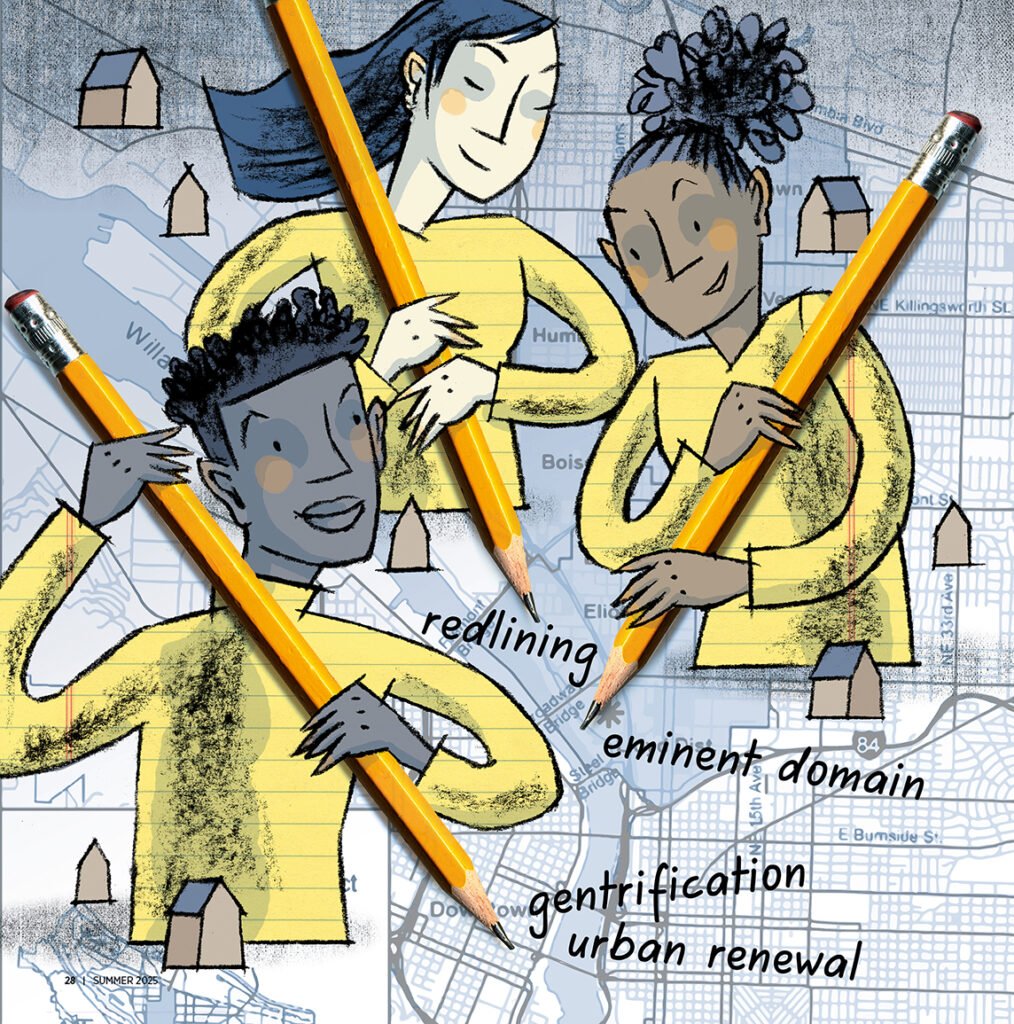

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

Teaching the essay begins on the first day of the unit, not the last. Sure, a teacher can hand out an essay template for students to follow. But those templates don’t allow for student passion and engagement in a topic. In fact, their formulaic nature constrains students’ ideas and damages their ability to write into their own understandings about subjects that matter to them. As Malik wrote in his end-of-semester portfolio essay:

I’ve never really liked any of my English classes. Maybe it’s just been my teachers, but I’ve always found it repetitive and boring. Read a book, analyze it, annotate it, pull quotes, and write an essay about the main message of the book. I like writing essays, just not those kinds of essays. In this class we have written the way I like to write. I feel like I have freedom and can express my opinions and feelings, which is something I have rarely been able to do in my past English classes.

Malik gets it: Essay writing should allow for students to express their ideas and feelings. When Rethinking Schools’ editors gathered and created an outline for a social justice classroom, we wrote:

A social justice classroom equips children not only to change the world, but also to maneuver in the one that exists. Far from devaluing the vital academic skills young people need, a critical and activist curriculum speaks directly to the deeply rooted alienation that discourages millions of students from acquiring those skills. A social justice classroom expects more from students. When children write for authentic audiences, read books and articles about issues that really matter, and discuss big ideas with compassion and intensity, “academics” starts to breathe.

When teaching the essay, I try to construct easy wins and early successes with the genre to build student confidence in composing. This year, I joined my friend and colleague Dylan Leeman in his sophomore English class at Grant High School in Portland, Oregon.

We started the year with the “Honoring Our Ancestors Essay: Building Profile Essays” from my book Teaching for Joy and Justice, which relies on student knowledge and anecdotes as evidence. For the second essay, we wanted students to grapple with knowledge from outside sources. We chose the definition essay, which provides students with enough internal structure so that we could use it as a building block in the essay genre. It was the perfect fit for our study of urban renewal in Portland. That’s why we did a victory dance when we read Zora’s end-of-semester portfolio evaluation where she wrote that with the Albina definition essay, “I really felt like I was using my writing for good. I felt like I was writing about something that actually mattered for once.”

Embedding Writing in a Unit that Matters

Of course, we didn’t teach the definition essay in isolation. When we decided to teach Raisin in the Sun, Lorraine Hansberry’s brilliant play about racism and redlining in Chicago, we knew that we needed to start by introducing students to Portland’s own history of redlining and racism before they read the play. To make sense of the history, students had to understand the terms “redlining,” “eminent domain,” “urban renewal,” and “gentrification.” We told them on the first day of the unit that they would write an essay defining one or more of these terms as the culmination of their study. For this to happen, the words needed to live in their minds, not from memorizing a dictionary definition, but by examining how these words bulldozed the lives of people of color in our city.

We revived and revised a unit I had assembled years before when I taught at Jefferson High School. (See “Rethinking Research: Reading and Writing About the Roots of Gentrification” in Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word, 2nd Edition.)

We started by asking students to look at data about the rise and decline of the Black population in segments of Portland’s Albina neighborhood from 1960 to 2020, which our friend and amazing math teacher Susan Pfhoman put together for us. The lesson raised questions about what happened: Why the rise in the number of Black people living in Albina? Why the decline?

Throughout this month-long unit, Dylan and I attempted to breathe life into the terms redlining, eminent domain, urban renewal, and gentrification — first through a mixer where students met Albina residents whose homes and businesses were destroyed to make way for freeways, a hospital expansion, the school district office, and other buildings for “the common good.” During the activity, they “met” people pushed out of their homes, like Thelma Glover, who went to church in the neighborhood, listened to music and danced with her husband at the Cotton Club down the street from their home, enjoyed meals at Citizen’s Cafe, shopped in the Black-owned grocery stores and businesses lining Williams and Vancouver avenues before their home was razed.

Through video interviews and photos, students encountered Paul Knauls, the charismatic owner of the Cotton Club and Geneva’s, the unofficial mayor of North Portland. Many students were struck by the story of Angel Bagley, a Jefferson High School basketball legend, whose barbershop Signature Cutz was closed after the building was sold during the gentrification gold rush hit Albina. According to Karen Gibson, a professor at Portland State University and who wrote “Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment, 1940–2000,” 476 homes in Lower Albina were torn down. In an interview she said, “Black people called it Negro Removal.”

This unit took students through local newspaper articles and archival photographs about the events and people they encountered in the mixer and interviews and videos with Albina residents that explored the history and the Black community’s resistance to the pushout, as well as their demand for the “right to return” to their historic neighborhood.

Preparing to Write the Essay

Once we completed the Albina portion of the unit, Dylan and I launched the essay. We told students: “For this definition essay, you will choose one of the terms that we’ve discussed during our exploration of Albina. Your essay will define the word. For evidence you will use statistics that demonstrate what happened to the community, as well as stories from the people in the mixer, readings, and film clips to help your reader understand how the term affected people’s lives.” This wasn’t news.

Of course, we could have just given the assignment. After all, we’d spent a month digging through news articles and interviews about Albina, but to engineer student success, we wanted students to gather and review their notes. This meant honing their definitions and rounding up statistics and stories from the unit as evidence.

We started with the definition: “In your small groups, create a definition of the following terms based on the stories from the mixer, readings, and video clips about the history of Albina. Write the definitions in your notebook.” We listed the words on the board: Redlining, Urban Renewal, Eminent Domain, Gentrification. “Don’t open your Chromebooks. We want these definitions in your own words.” Xavier, Zora, and Ian wrote:

Redlining: An artificial line restricting where people could live based on their race.

Urban Renewal: The destruction of old homes and businesses to build new projects.

Eminent Domain: A law that gives governments the right to destroy homes for infrastructure projects.

Gentrification: Wealthy people moving into a poor area creating rising prices and forcing displacement.

Over the course of the first quarter, Dylan and I discovered that this class works best when they work collaboratively on an assignment. We wandered through the tables to make sure students had a strong grasp of the terms. When it looked like most students had their notebooks opened and writing completed, we asked different table groups to share their definitions. “If someone uses details that you didn’t include, add their ideas to your work.”

Once students had good working definitions, we asked them to comb through their Albina materials and locate the number of homes and businesses destroyed, as well as estimates of the loss of wealth. This sounds easier than it was. Different newspapers and historical documents gave varied numbers, so this was also an exercise in citing their sources. This time, groups shared their information on the whiteboards with their source because it gets monotonous hearing the same statistics, and we try to build movement into the 90-minute class period.

For the next round of information collection, we asked, “How did redlining function to restrict people of color, particularly Blacks in Albina?” “What function did eminent domain play in the eviction of Albina families and businesses?” We knew that several students lived in the Albina neighborhood or had family members uprooted. “If you have family stories that connect to this, include those anecdotes or vignettes as well.” This question moved a number of students to discuss the history of Albina with their parents or grandparents, capturing stories of what “used to be” — the corner where the More-For-Less grocery store stood for years, or the drive-through dairy where families picked up their milk in glass jars.

Recognizing that this didn’t happen only in Portland, Dylan’s 4th-period student, Isaiah, came in after school for the first time asking Dylan for help researching how his family’s apartment in Seattle was lost to gentrification so he could add that to his essay.

During the Albina study, students had created and annotated a map of the area, noting landmarks, names of businesses and people affected by urban renewal and gentrification. Their Albina posters still hung on the classroom walls. To find stories, they retrieved their posters and examined those as well as their other articles and notes. Finally, we asked students to review their handouts to locate quotes that could be used in their essays. “Highlight the quotes and then write them in your notebooks. Note the source.”

Although the steps I described might sound tedious and time-consuming, let me say that slowing down the process of writing to demonstrate how to retrieve evidence, search articles for quotes, and review source materials for stories is the work of writers. Students at Grant take eight classes each semester. That’s a lot. Also, they are teenagers who accrue absences, who forget, whose relationship busted up at lunch, whose parents split up over the weekend, who worry about getting on the baseball or soccer team instead of focusing on their classwork; therefore, we take the time needed to make sure students are ready to write the essay.

Writing the Opening

Once students were awash in statistics and stories and had honed their definitions, we gave them sample openings from definition essays Dylan and I had written on the Oregon “Donation” Act as models; the content was adjacent to Urban Renewal, but our topics wouldn’t steal students’ thunder when they wrote theirs.

Definition: Opening Sample #1

The term “donation” comes from the Middle English donatyowne, from Latin donation-, donatio, from donare to present, from donum gift; akin to Latin dare to give. The legal definition is the “voluntary transfer of property/money.”

Considering this definition, the Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850, which gave white male settlers 320 acres and white married couples 640 acres of land in the Oregon Territory, wasn’t a donation. A better term is theft. Let’s call it what it was: The Oregon Land Theft Act of 1850.

“In your small groups, read over the sample essay openings,” we instructed. “Which ones did you like? Why? Which ones will you try out in your essay? Remember: Essay is French for ‘to try, to attempt.’ Some of you have personal connections to Albina and gentrification, your stories can be part of the essay. We want you to try new writing strategies as you develop your writing voice. Write one or two openings in your notebook. Be prepared to share.”

Early on, when Dylan and I decided to teach together, we made a choice that we would invite students to use first person pronouns and personal evidence in their essays, which contrasts with what is traditionally taught about essay writing. Instead of pushing them to write from a dispassionate distance, we encourage them to use their voice and their perspectives in their writing. At the end of the period, we asked a few students to read their openings out loud, so that their classmates who struggled could review theirs and make changes. At the end of the day, we gathered their notebooks, typed up a few of their openings as models, and shared them the following class period as inspiration for students who had difficulty starting or who had missed class. This practice of immediately examining student writing to share is part of our writing routine that honors student work and establishes that writing is communal, meant to be shared, and creates the habit of working collectively to improve their work. We are all trying together.

Great openings from your classmates: Using these as models, sharpen your openings.

1. The dictionary says that eminent domain is “the right of a government or its agent to expropriate private property for public use, with payment of compensation.” What that doesn’t show is the racism behind it, the homes and lives that this law destroyed.

Uses the dictionary definition, then follows it with a pithy statement of the effects of eminent domain.

2. The dictionary defines urban renewal as “the redevelopment of cities, typically getting rid of slums.” I prefer to call it blatant racism and classism.

Short. Sharp. Pithy.

3. Oxford Language Dictionary describes gentrification as “the process of making someone or something more refined, polite, or respectable.” But is that really what it is? Albina was a neighborhood with a predominantly Black population. The community thrived for many years and was a safe space to many people. However, the city of Portland had other plans for Albina. Albina was declared “a slum, with a blight that must be removed.” What was this blight to the city? People. People living their own lives, with their own homes, and their own futures. Anybody with half an ounce of common sense can see what happened here. Nothing in Albina had anything to do with “making the city better.”

Note the use of the dictionary definition, then the “talk back” to set the dictionary straight about what that meant for Albina.

Writing Evidence Paragraphs

The following class period, we told students: “You have your opening. Now write the essay in your notebook during class today. Don’t worry about making mistakes. Write to get your ideas down. We will return to the essay and revise it. If you come to a section where you are not sure what to write next, just write TK, which for journalists means ‘to come.’ If you’re stuck, go back to your notes, your quotes, your statistics and use one of those to get back into your essay. Sometimes when you write quickly, you find new insights you didn’t realize you had. This helps you break out of your writing pattern and into new ground.”

I’m not a fan of timed writing unless it’s done with the understanding that it’s not a final draft, but sometimes I can worry a sentence instead of worrying the essay, and students can too. Dylan and I wanted them to have a block of writing so we could examine what they knew about writing an essay as well as the content we’d studied. Catching the writer while they are writing is the best way I’ve found to move students to revise their work. Instead of spending hours making comments on papers after they’ve completed their essay, Dylan and I quickly scan them while they are still in the act of composing to see if we need to redirect them.

After scrutinizing student papers to see what they did well and what we needed to circle back and work on more, Dylan and I selected sample students’ evidence and concluding paragraphs for a revision lesson. After each paragraph, we noted some writing moves that each student made to enhance their work: “In your small group, read and discuss the sample evidence paragraphs. Which ones did you like? Why?”

Great evidence paragraphs from your classmates:

Using these as models, sharpen your evidence.

1. Rebuilding neighborhoods. Making a city “better.” This is not what it felt like for many people living in Albina. Ms. Donna Maxey was living in Albina when in 1961 she was forced out of her home because of the expansion of Emanuel Hospital. She states, “I would dream about that house until I was in my 50s.” The loss of her house was devastating, as it would be to anyone. The hospital, of course, recognized this feeling and decided to apologize. But all that Ms. Maxey seemed to get was a lousy pancake lunch. She didn’t get her house back, or the real apology or funds that she deserved, she got a cover-up apology. A free pancake lunch to make the hospital appear better. During the expansion, more than 300 homes and businesses were torn down to make room for the new building.

Strong evidence paragraph because it uses a specific story from a person affected by urban renewal. Good use of quote. Good use of specific statistics to make a point. Also, some attitude and suggestion that this was unfair, a discussion of the evidence.

2. Who gets to decide what is “good” land, and what is “bad” land? In the 1970s in the Albina neighborhood the Portland Development Commission did just that. They decided that the Albina neighborhood was a “slum,” an “eye sore”; they also called it “urban decay.” The Portland Development Commission, which was really just a group of white men, proposed a thing called Urban Renewal. According to them, Urban Renewal was a financing mechanism used to improve “economic viability” to specific areas. This was all a sugarcoated presentation of what they were actually going to do: Remove Black People.

Strong evidence because it names who shaped the eminent domain project in Albina. Also, this piece has a strong voice and attitude.

Then we returned them to their own work. “What evidence is missing in yours? Statistics? Stories? We noticed that most essays needed more of your thoughts. What did you think about what happened? What understandings or revelations did you have about Albina? Add those ideas into your essay.”

Once students had revised their evidence paragraphs, we had them partner up and share their work. We told them to look for what was working in the draft, not for what was wrong. “Start with what’s right. Don’t focus on punctuation or spelling errors. What did the writer do that helped you understand more about eminent domain or urban renewal? What evidence did your partner use? Is there something missing or some quote or story that you used that might help them in their writing? Share that.”

Working through the essay with a partner and learning how to use classmates as resources are habits students need to nurture if we want their writing to grow. There are too many of them and too few of us; they need to develop strategies for getting feedback, and we need to step back from commenting and redlining and move into our role as conductors of the writing orchestra. That said, we also need to teach them how to respond in a way that moves their classmates’ work forward.

Because we work with students in the midst of writing, we can stop and talk with them about their work, noting what we love about their piece or an insight they had that made us laugh or think. Often, it prompts us to encourage a student to share with a classmate writing on a similar topic or to share an additional resource. It’s another way of letting students know that we read their work and take them seriously.

Writing the Conclusion

As the final step in the writing/revising/sharing process, we had students review and revise their conclusions, which can be the hardest part of essay writing unless they use the old “here’s what I told you in my essay” conclusion, which we discourage. Once again, we gave students models from classmates and asked them to read them, discuss as a group, and think about what kind of conclusion the writers used.

We told them: “Conclusions can be tricky, so try a few kinds and see which one your group loves the most.” We shared four strategies:

- Summary: An overview of what happened and how that constitutes eminent domain or gentrification or whatever definition you are working with.

- Circle back to your beginning. Return to the story or your opening, like Malik’s “Whites Only” sign or Andrew’s story of the Vanport flood. Tie that story together with your definition.

- Suggest a possible solution to the problems urban renewal or gentrification created.

- Think ahead: What might people ask themselves before another neighborhood is razed?

As one student wrote in his semester evaluation of his writing of conclusions:

This year I was taught a different way to write conclusions than I had been taught before. I was taught in years past to just go over what you have written in them. In my Albina definition essay, this is my conclusion: “There were people in their neighborhoods living life, then the government came and kicked them out, and bulldozed those people’s homes. They built new things in these neighborhoods. It is important to understand that these people were kicked out because of their color and not because of their homes. These people should have some sort of input in the neighborhood so it stays with them.” I kind of just spoke from the heart.This conclusion I think was one of the best conclusions I have ever written.

Examining Writing to Learn

Under the category “You are never done,” Dylan and I asked students to return to their essays and analyze their work. After they typed the final draft, we said, “Look at the first draft of your essay. Look at your ‘final’ draft. Note three to five changes you made between the drafts. Did you add more evidence? Did you discuss the evidence? Did you write a new opening or conclusion? List those changes and talk about why you changed them and the difference they made in your writing. What will you take with you to your next essay?”

Students discussed their changes at their table groups and created a poster of the kinds of changes they made: Adding more evidence, reworking sentences, writing entirely new openings and closings.

Over the years, we’ve found that this self-analysis helps students internalize the lessons we taught and the changes they made in their writing. Sam’s analysis came during his end-of-semester portfolio writing:

One of my biggest flaws in writing is that I HATE revising. It feels like painting a giant landscape, only for somebody to tell you that you painted the Sahara Desert and not the Grand Canyon. And the worst part is, you know they’re right. Truthfully, my first draft of the Albina definition essay was horrendous; it had extremely bland writing since I didn’t know nearly enough about the actual events yet. My first draft had zero passion behind almost every paragraph and felt clunky. However, after Andrew gave me a bunch of comments about it, I went back through and worked a lot more on, well, everything. This essay is an example of a much more passionate essay, especially when compared with the original.

Another benefit of this final piece of student metacognition about their essay writing is that Dylan and I can skim their drafts, setting them side by side to witness the changes they made. We don’t need to make comments on the final drafts because students had already annotated them for us. We did make notes about what we needed to teach in the next round of writing.

Students joked that this was the longest unit they’d ever been taught because we paired the Albina unit with Raisin in the Sun. “You’re not wrong,” Dylan answered. But when we looked back over their portfolio evaluations, the evidence of their growth from the tender first shoots of writing to the way they harnessed evidence and wrote with conviction — and not a little bit of sass — was worth it.

At a moment in history when lies and mistruths are spread like dandelion puffs in the wind, it is critical that we teach students to think and write with passion and power about the world. As teachers, we have the power to open up the possibility that student writing can be as “free” as Malik suggests and that students, like Zora and her classmates can “write for good” instead of writing for a rubric or for a grade.