“More People Get What They Need”

First Graders Explore Light, Sound, and Accessibility

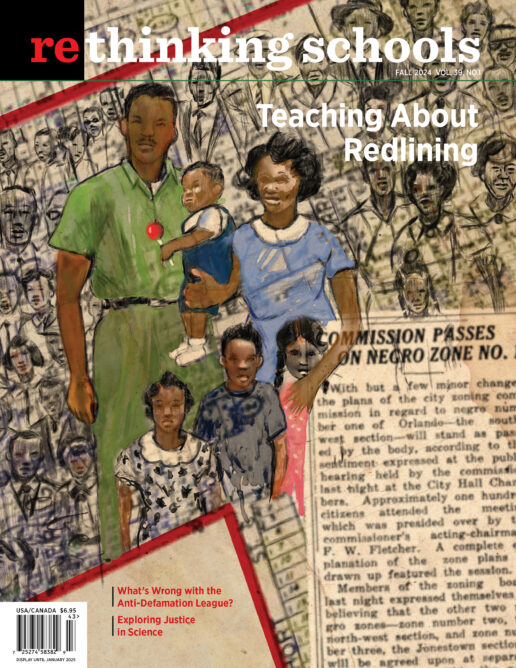

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

My 1st graders and I sat together on the rug watching a video of a fire alarm. The alarm utilized a flashing light and sound with spoken directions on how to leave the building safely in an emergency. I chose this alarm so that my students would be able to clearly see light and sound used in tandem — and as a model for their own designs. Students realized because of the way it used light and sound together, this fire alarm was more likely to be accessible for someone who cannot hear.

Dorian raised their hand. “Mrs. Arnett, this alarm is using light and sound together, but my mom doesn’t speak English. How would she know what to do?” This was met with concern about family members who don’t speak English.

“Ah, if the alarm is in English then it isn’t accessible,” I remarked. I saw the light bulbs. My 1st graders understood. Dorian’s question was the perfect segue to the culminating project for my unit on light and sound.

Radical empathy and science aren’t often thought of as going hand in hand, yet I’ve found that my young students can understand the complexities of both. In this unit on light and sound, I wanted to build empathy by getting students to understand the importance of accessibility and its effects on the world around them. My goal was to weave our study of light and sound with an exploration of accessibility in hopes that students could draw their own conclusions: that others experience the world differently, their needs are important, and we all need support to access the world.

Context

Hightower Elementary is a STEM-focused public school in Doraville, Georgia. The school serves a tight-knit community that mostly resides among three apartment complexes nearby. The school is primarily composed of students who identify as Latine, hailing from many different parts of Latin America. There is also a sizable Bengali community, as well as some Black and white students. Students are aware of the need for translation services for their families. Students’ language needs are a driving force in planning lessons that provide my students with voice and choice.

In Georgia, 1st graders must demonstrate their knowledge that sound is caused by vibrations, as well as what a light source is and what happens when a light source is blocked. As part of the standards, students determine why light and sound are often used in tandem for emergency signals.

For their cumulative activity, students look at different emergency signals that exist in the world and how they use light and sound together to display the message that there was an emergency. Then, I ask them to create an accessible emergency signal that uses both light and sound in tandem. But before they start this project, we needed a common definition of a “signal” and what being “accessible” means.

What Is a Signal?

“What is a signal?” I asked as we sat together on the rug. Many students raised their hands to give examples.

“We cross our fingers to let you know we need to go to the restroom.”

“We make an L to go to the library.”

I noted that these were visual signals that relied on light to be seen. They also talked about the auditory signals we use in our classroom as an attention-getter, such as clapping or using a chime.

“The chime tells us we need to be silent and freeze,” said Alia. A few noted that those are auditory or sound signals. Josie simply pointed to the fire alarm in our classroom. Bernardo chimed in that we use it to signify when there is an emergency and we need to leave the building because of fire. I wrote students’ answers on a class chart we used to track student thinking.

“What do you notice about the fire alarm? Talk to your neighbor.”

Students began chattering about what they saw. “It has a flashing light.” “Es rojo.” “It is super fuerte!” Times like these are filled with a mix of English and Spanish. Guards go down, and the chatter is confident and accessible to their peers.

We pulled back together and I repeated, “What do you notice about the fire alarm?”

Briana pointed out that there was a flashing light, but also a really loud siren.

“But why are there both?” No one responded. “OK, we have an idea of what signals are, but why do we use signals?” The class turned to their neighbors to talk. Giving students time to express their opinions orally, inquire, justify in whatever language they see fit, and simply talk is always in the forefront of my mind. I sit in the discomfort of not knowing what they are speaking about all the time, but this experience is one my students face daily. Language and access and power around language is something my students encounter regularly.

Once we identified the signals we use in our classroom, we watched a few videos of various emergency signals from different contexts, one just using sound, one using only light, then finally a signal using light and sound in tandem. For each signal, we talked about its purpose, then its pros and cons.

“Why is this signal using sound? What is the purpose?” I asked.

“So people can hear it and know that they need to leave the building,” said Jonathan. “It is like the alarm clock in my room. It tells me things with a noise.” A few students agreed and nodded.

“Any other reasons?” I probed.

“Loud noises usually make people move quickly,” said Bernardo. “They know something is wrong.”

Next, I showed them an alarm that uses only a flashing light to signify an emergency. “Why does this signal use light?” I asked again. A roar of “It is so bright!” and “It is flashing!” filled the classroom.

“Why do you think they specifically chose a bright flashing light to signal an emergency?” I asked.

“It isn’t normal or regular like a lamp,” Bernardo said. “It will make people move!”

With each signal we noted the light source or vibration that created it. We had also explored volume and pitch, as discriminating pitch was something important when thinking about accessibility. Students had noticed that some sounds, such as loud higher-pitched sounds were more easily heard than others. They had also learned about artificial and natural light and worked with shadows. Each of the lessons helped them better understand light and sound to complete their final project creating an emergency signal.

When we talked about the pros and cons of each alarm, one student said the sound alarm could be a hazard for someone who couldn’t hear it. I asked students what they thought might happen if they were in the classroom and they had headphones on or simply couldn’t hear in a typical way. Students quickly caught on that totally using sound can be detrimental to someone who cannot hear or whose hearing is obstructed by some other sort of sound. I then had them speak about the pros and cons of an alarm as a flashing light. The class realized that perhaps if someone was sleeping, they couldn’t see, or the light sources were blocked, that they would not receive the message.

“How might it feel if you can’t experience the signal in the way that most people do?” In posing this question over and over, I hoped to guide the class in the understanding that others might experience the world differently, and that their experience should be honored.

Alia noted that it might be scary to not be able to see in an emergency. Others agreed that not hearing an alarm might also be scary. Throughout this discussion students referenced how “unfair” it would be to be left in an unsafe situation just because of how their bodies functioned.

“What do you mean by ‘unfair’? Why would having a signal some cannot understand or use be ‘unfair’?” I asked.

“Because everyone isn’t getting what they need,” Keran said. “If we use them both, then more people get what they need.” Other students agreed.

I define fairness early in the year with students as it becomes apparent that my 6- and 7-year-old students tend to equate fairness with equality. I make it clear that in our classroom everything will not be exactly the same or equal for each student (e.g., some students will meet with support teachers that others will not meet with), but we will be fair, and everyone will get what they need. Our needs are different, but important.

“So how do you think people feel if they find out they can’t hear or see an emergency signal?” I asked. Shouts of “sad,” “scared,” and “frustrated or angry” filled the classroom.

What Does Access Mean?

Following our analysis of different types of alarms, we defined the word access, and students noted that when something is “accessible” it seems as though all people can do it regardless of their ability — or language. The language piece of this definition was something that I simply hadn’t thought of. However, reflecting back, it makes so much sense that my students, most of whom are bilingual or from immigrant families, would be invested in language accessibility. They often interpret for their families, read signs, listen to messages, etc. They understand that knowing English puts you at an advantage.

Dorian’s comment about their mom not being able to understand an alarm that uses English motivated the class to think about accessibility in the community. “My family doesn’t speak English either!” other students chimed in.

“We’ve been talking about using light and sound together. Why is that?” I asked.

“Because if the signal only has a light a blind person wouldn’t see it,” Alia said. “And if it only has a sound a deaf person wouldn’t hear it.”

I nodded. “Exactly, and you all reminded me that if the sound is in a language they don’t understand, then they can’t use it.”

Students noted there might be a lot of people who couldn’t understand the emergency signals. “Who else might be missing out?” I asked. Our school has a few Deaf and hard of hearing students, and some students noted that it may be difficult for them to understand the alarms without a light element. During these discussions some students asked if there were blind people in our community, as they hadn’t met any. We talked about how blindness varies, and you can’t always tell that someone has a disability, but that just as we are different and have different needs, there are most likely members of our community that would benefit from that kind of accessibility.

Design Projects

After four exciting weeks of study on the science of light and sound, I introduced the culminating project: Design an alarm that uses light and sound to alert someone of some kind of emergency. For this project, Students work in heterogenous groups. In all design projects we use a school-adapted engineering model called the A.B.C.D.E. model with each letter representing a different task students need to accomplish as they complete their builds.

| ASK | What is the problem? What are you being asked to do? |

| BRAINSTORM | Brainstorm ideas with pictures and words. |

| CREATE A PLAN | Create a plan of action, including materials and responsibilities. |

| DESIGN | Build your design and draw/label it in your STEM interactive notebook. |

| EVALUATE | Test your design. Go back and make it better or write about potential changes. |

The model is integral to the learning in the school and referenced at least monthly. Not only is the model used in the engineering process, but we also use it in other subjects, such as writing.

Because of earlier class conversations, students understood their group’s design must be able to be used by someone Deaf or hard of hearing, blind or with limited sight ability, and anyone who may not speak the language of power in their area. We review these requirements as part of the design step.

During the brainstorm, students draw and label their drawings in their notebooks. Once each student has an idea, they explain their designs to a group of peers at their table.

Keran shared his design of an alarm that had a flashing red light.

“The signal wouldn’t be accessible to [my brother],” Emely said, noting that their brother was red-green color-blind. “He could get confused.”

“If he can’t see red or green, what color would better help him access the information?” I asked. The group thought for a while and settled on white. I hadn’t thought about this specific scenario before this justification session. Bernardo asked why an ambulance uses red lights.

Some students also seemed critical of designing an emergency signal that relied on electricity to power their lights or sound makers. When asked why they were so vehemently against an electric signal, Josie spoke about a time when an entire apartment complex was without power or internet for at least a day after a large hurricane hit the area. Students in the apartment complexes that serve our school lost power many times following this hurricane. They were concerned that an electric emergency signal would not suffice if they lost power in the building. “What is the point in an emergency signal if it doesn’t work?” a student asked.

As each child presented their notebook brainstorms to their group, Isiah showed a box with a bell that had a string attached. It also had a flashlight with the words “Get Out” written on it.

“Isiah, why are there words on the flashlight? What is it supposed to do?” Bernardo asked. Isiah responded that the words would create a shadow on the wall that others could read.

“But what if you can’t read, or read English?” Bernardo pressed. They compromised on a stick figure of someone exiting a door.

Once students had justified their designs to each other, each table group chose one design to pursue further. The third step in our process, create a plan, requires students to write down the steps that they will take, and also anticipate problems they may encounter. In their groups, students created a step-by-step plan of what materials they would need, and what procedures they would follow to build their chosen designs. I find that discussions ramped up during this portion of the process. My role is not to solve their disagreements, but to remind students of the goal of accessibility and facilitate dialogue so that they can solve their differences themselves.

During the design step that follows, students pick out their materials and actually create their designs. For this activity, I gave students a variety of materials to choose from. They had basic recyclables such as boxes, toilet paper tubes, plastic water bottles, and old wipes canisters to serve as bases. They were also able to choose from various sound devices such as jingle bells, handbells, and noisemakers. I also gave them recording buttons often used by dog trainers. Students could record their own messages or sounds and play them when the button was pushed. They had access to finger strobe lights, flashing laser pointers, flashlights, small puck lights, and reflective bike safety flashing lights. They could also use foil or small mirrors as reflective surfaces. Finally, they were able to use scissors, popsicle sticks, pipe cleaners, tape, glue, string, and rubber bands.

Some students’ ideas required items that I couldn’t provide such as bullhorn sirens or dogs. However, because they were able to use the sound recorders, some chose to find the sounds online and record them from the internet. I also offer an abstract design choice — allow them to draw parts of their designs in their notebooks — to eliminate some of the limitations students might face from a lack of materials. Generally, students preferred to actually build their designs, but perhaps had some element that would be in theory.

To test or evaluate students’ emergency signals, we had a drill day. During this day students used their emergency signals with the class, and their peers in other groups provided feedback on each signal’s effectiveness. Students created a variety of emergency signals, all of which used light and sound elements together.

One group used a small box as the base and taped handheld jingle bells to the side of the box. They then affixed two bike flashing lights, one red and one blue. A student shook the box to make sure the bells rang.

Another group created a shadow puppet of an X that was taped to the side of their wipes canister. The tape was loosened enough that it could be moved up when the signal was not in use or down during an emergency. A flashlight shined their message on the wall. They also added a recording button with both an alarm sound and the message “This is an emergency. Please go outside” that they themselves recorded.

Some students created a hanging alarm, taping jingle bells and finger strobes to the box. During an emergency they would hang the signal from the ceiling and spin it so that both the bells would ring and the lights would shine around the room.

As students tested their designs we reflected: Were the lights bright enough to catch someone’s eyes? Was the shadow big enough or clear enough to be seen by others? Was the sound loud enough or piercing enough to be noticed? Was the sound distinctive enough to be used as an alarm for an emergency? Then students went back to think about how they could change their designs.

During the final evaluate step, I also asked students to reflect on the importance of accessibility. “Why do you spend time to learn about this?”

“We want to keep everyone safe,” shouted a student. “If we can’t think of ways to be accessible, not everyone is safe.”

“Yes, safety is important, and we do want to make the world more accessible for everyone. Even if you haven’t met someone who needs some of these accessibility measures, it’s important that we think about other people.”

“We all live together,” said Brandon.

Reflections

As one student said about the design of an alarm during this unit: “What’s the point of it if it isn’t helping everyone?” This stuck with me. What’s the point of this assignment, if it isn’t helping my students to access power in their learning, build empathy, and understand accessibility in their community?

With more time to implement this project with my class I would put a greater emphasis on the history and laws of accessibility and dive deeper into how disability rights activists and civil rights activists fought for change. I also dream of exposing students to designs for technology in which accessibility is at the forefront of the design rather than incidental, so students could see how inclusion can be the driving factor behind innovation.

Science cannot be taught in a vacuum. The world impacts science as much as science impacts the world. Our job is to connect topics to students’ lives and the lives of others. Science can act as a catalyst to develop radical empathy — to better understand the world and the needs of the people around us.