Still Teaching Against the War(s)

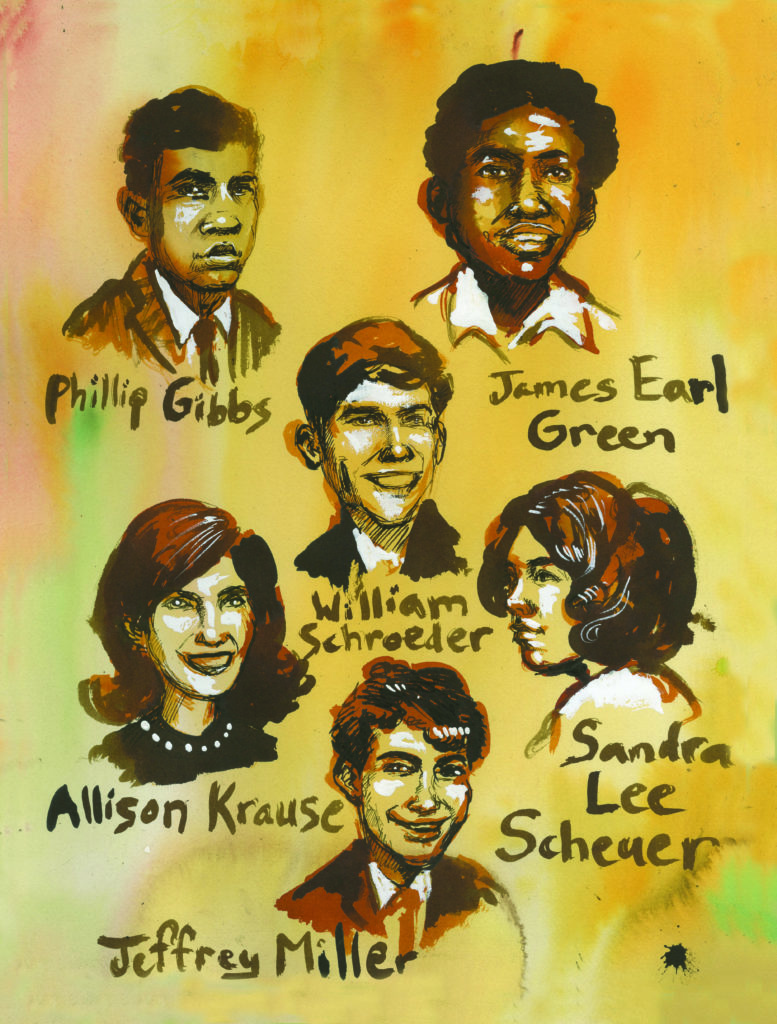

Illustrator: Molly Crabapple

Fifty years ago — on April 30, 1970 — the U.S. military invaded Cambodia in an expansion of the Vietnam War. In response, students across the country staged massive demonstrations. Two days after the invasion, on May 2, students at Kent State University in Ohio burned the ROTC building. Two days later, the National Guard confronted unarmed protesters on campus. Guardsmen shot 67 rounds in 13 seconds, killing four students — Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller, Sandra Lee Scheuer, and William Knox Schroeder — and wounding nine others.

College students across the country went on strike, shutting down more than 450 campuses. At Jackson State College in Mississippi, 11 days after the Kent State killings, police opened fire on protesting students, killing 21-year-old law student Phillip Lafayette Gibbs and 17-year-old high school student James Earl Green, and wounding 12 others. Dr. Gene Young, then a student, remembers: “Young Black males were being sent to Southeast Asia in disproportionate numbers, and we were concerned about that, in addition to the historic racism there in Jackson, Mississippi.”

Fifty years later, our wars seem never-ending and ubiquitous. A high school senior graduating this year has never known a day in their life when the United States was not at war. U.S. troops still fight in Afghanistan. The United States continues to kill people with drones in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, Syria, and Libya. Yemen is also a target of U.S. proxy bombs. As the Guardian has reported, the United States has given “full support to a relentless air campaign where Saudi warplanes and bombs hit thousands of targets, including civilian sites and infrastructure, with impunity.”

*** Download a free copy of Teaching About the Wars by clicking here ***

This past December, a U.S. drone strike killed four in Afghanistan. Here’s what the Intercept reported:

A 25-year-old Afghan woman there named Malana had recently given birth to her second child. When Malana developed postpartum complications at home, her father-in-law, mother-in-law, and sister-in-law took her in a car to a clinic. On their way back home, all four family members, plus the car’s driver, were killed by an American missile launched from a weaponized drone. All were burned to ashes.

Then in January, President Trump bragged about the assassination-by-drone in Iraq of the Iranian Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani.

And there are the less deadly but nonetheless outrageous manifestations of U.S. militarism around the globe, like the expansion of the U.S. airbase at Henoko in Okinawa, where the military is stuffing 21 million cubic meters of dirt into Oura Bay, one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. The Indigenous Uchinanchu people of Okinawa continue to hold daily sit-ins in opposition.

Yet despite the horrific violence, and ecological crimes, paid for with our money — money that could go for schools, for green infrastructure, for health care, for affordable housing — there are no massive protests here. Similarly, there is far too much silence in our curriculum.

Following Trump’s killing of Suleimani, Rethinking Schools editors wrote to readers offering a free download of our 2013 book, Teaching About the Wars , hoping to seed more teaching about the antecedents of today’s conflicts. (In just a month, the book was downloaded more than 1,000 times, and it is still available for free download at our website.)

Although the articles in Teaching About the Wars grew out of the “war on terrorism” following the Sept. 11 attacks, the launch of the war in Afghanistan, and then the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the teaching strategies, the history, and many of the resources highlighted in the volume are still relevant today. For example, lesson suggestions encourage students to read and evaluate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “A Revolution of Values,” in which he denounces the “giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism.” A lesson, “Whose Terrorism?,” asks students to define “terrorism,” and then to apply their definitions to world events. Their conclusions about their own government challenge the notion that terrorism is something that only “other people” do. “The U.S. and Iraq: Choices and Predictions” looks at U.S. policy toward Iraq going back to the 1980s — a history that also sheds light on today’s relations with Iran.

In her introduction to Teaching About the Wars, editor Jody Sokolower wonders about what it does to us as educators, and what it does to our students, when we are silent about the wars waged in our name. As Sokolower writes, silence is “heavy with potential meaning:

• War is endless and inescapable, part of the wallpaper of life.

• The Middle East conflict is another one of those depressing subjects that is too complicated to understand, too impossible to change, and leading us toward an inevitable Armageddon. . . .

• Who are we to question, when our textbooks bury our ongoing wars in a few comforting paragraphs?”

Yes, there is so much injustice it is sometimes hard to know how to respond, how to act with morality, solidarity, and efficacy. But for now, for those of you who are educators, we want to ask you to think about your classrooms, and how you are teaching against war and militarism. No doubt this will look different for high school history teachers than for 5th-grade teachers and for pre–K teachers. (Although as Ann Pelo argues in her article in Teaching About the Wars, it is very much the work of pre–K teachers, too.)

Of course, if we take an honest look at the history of this country, we see how expansion and imperialism was baked into its origins, how from its inception the United States waged war against African Americans, against Indigenous peoples, against Mexicans, against Hawaiians, against Cubans, against Filipinos . . . and the list goes on. Part of teaching against militarism means looking carefully at how the very nature of the United States depended on the domination of colonized “others.”

And we ask you to think about how to respond to militarism in your schools. Far too many schools have Junior ROTC programs, which especially target working-class communities and communities of color. As Sylvia McGauley describes in her fall 2014 Rethinking Schools article, “The Military Invasion of My High School,” JROTC introduces weapons training to students, partners with the NRA to sponsor marksmanship contests, and models “authoritarian militaristic solutions to problems.” And even where there may not be a formal JROTC program, military recruiters too often sell a life in the Armed Forces as the route to personal fulfillment.

We invite you to write about and submit your teaching experiences for possible publication in Rethinking Schools. We want our magazine to be a site for conversations about how we help students understand the nature of social injustice — including war and imperialism — but also how we can work to make things better.

In his famous speech against the Vietnam War at the Riverside Church on April 4, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. ended with a challenge to his audience: “Now let us begin. Let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter — but beautiful — struggle for a new world.” This is a struggle that also goes on in our schools. Let’s remember that every day we walk into our classrooms.

Download a free copy of Teaching About the Wars by clicking here.