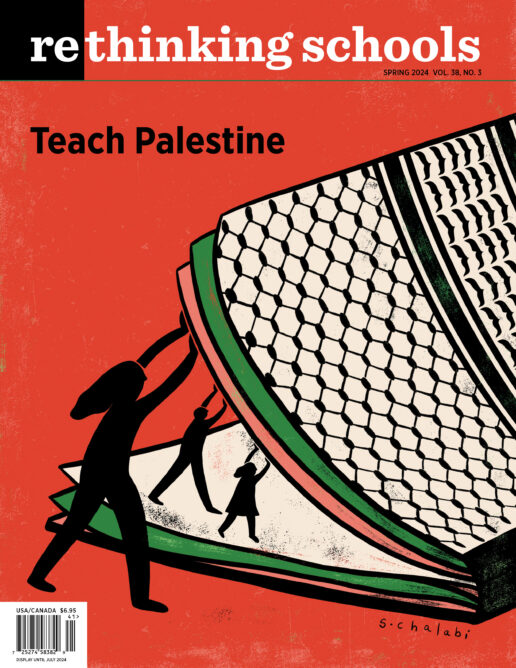

The Story of the Chicago Young Lords for Teachers

In March 2020, at the start of the pandemic lockdown, I found myself tasked with leading at-home learning for my children while their school community created a plan of action for the weeks (turned years) to come. As a born and bred Chicago Boricua (a term with Indigenous Puerto Rican roots that today denotes awareness of our Afro-Indigenous history and deep cultural pride), I didn’t have access to stories of Boricua resistance and self-determination until I became an adult, but the crisis provided an opportunity to shift this generational trajectory.

I planned several lessons on Taíno and African resistance movements against Spanish colonizers in Puerto Rico for my children, and chose the Young Lords as a modern account of the Boricua freedom movement.

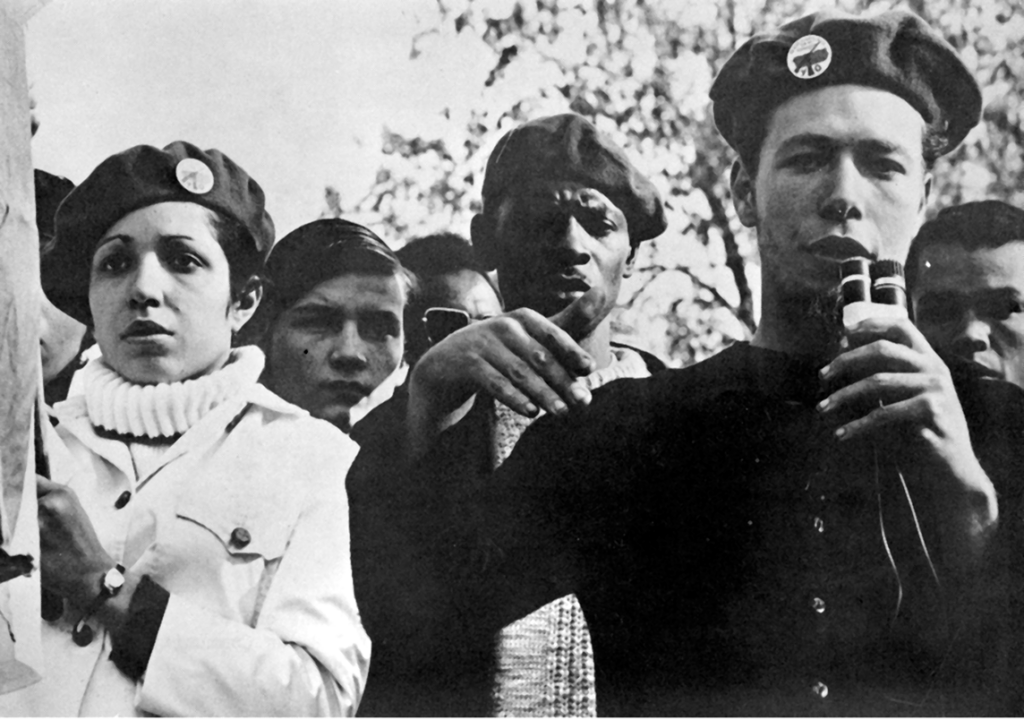

In the context of burgeoning movements for Black freedom, women’s liberation, and against the Vietnam War, José “Cha Cha” Jiménez steered the transformation of the Young Lords in 1968 from a Chicago street gang into a political organization. They organized against displacement, gentrification, structural poverty, and police brutality, and led survival programs that included a children’s breakfast program, a health clinic, and a dental clinic. Known as the Puerto Rican counterpart of the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords partnered with Fred Hampton, the Illinois chairman of the Black Panther Party, to form the original Rainbow Coalition, a class-conscious formation that also included poor whites from Appalachia. The Chicago Young Lords’ work received national attention in the Black Panther newspaper, and eventually spread to cities throughout the United States, including New York, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia.

As the streets of my city sat eerily empty, I dove into Johanna Fernández’ The Young Lords: A Radical History (University of North Carolina Press, 2020) to prepare for my daughters’ lessons. To my surprise, I found connections to my life in many of the pages. The story of these young revolutionaries with big, bold dreams was closer to my own than I had ever realized. Many of the Young Lords, including Cha Cha, attended Lincoln Park High, the same school I attended. Never once, while hopping on a bus, then a train, and walking on Armitage Avenue to get to my magnet school, did I imagine that Puerto Ricans once lived in Lincoln Park. By the time I was a student there in 1989, the neighborhood had long been gentrified. The work that the Young Lords had led against it had been erased. Not a single Puerto Rican flag was in sight — a hard feat to pull off, as any Boricua can attest!

As I read on to the section on the New York Young Lords in Fernández’s book, I found myself returning to the chapter about Chicago. My bias as a Chicagoan surely played a role in this, but it was my astonishment at the Chicago Young Lords’ transformation from a street organization to a political group that kept pulling me back. It was different from the formation of the New York Young Lords, who were mostly college educated activists and were political before they followed in the footsteps of the Chicago Young Lords. And then there was the story of Cha Cha and his development as a strategic and internationalist leader. The Chicago Young Lords were unlikely, but fierce, protagonists in the history of that era.

Then June 2020 happened.

As I watched protests, mostly led by young people, unfold across Chicago and the rest of the country, I couldn’t help but notice the similarities between the story of Manuel Ramos, a Chicago Young Lord murdered by an off-duty Chicago police officer, and the horrific examples of police violence that resulted in the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. When Black and Latinx gang tension in Chicago came to a head and added another layer of complexity to the uprisings for Black lives, it became even more critical to study and understand the Chicago Young Lords’ transformation and the emergence of the original Rainbow Coalition.

In the spirit of study and struggle, a ’60s freedom movement practice grounded in the necessity to engage political education alongside collective action toward liberation, I reached out to about 20 educators I thought would be interested in discussing The Young Lords: A Radical History. I emailed Johanna Fernández, associate professor of history at the City University of New York’s Baruch College, who agreed to lead the virtual discussion from New York. Our meeting became a powerful evening of truth-telling, learning, and healing. One person shared how their father joined a street gang to protect themselves from white ethnic gangs just like the Young Lords did in the Lincoln Park neighborhood to which their parents had been displaced. Another educator, a Black man, shared the exhaustion he felt navigating spaces of education disproportionately dominated by white women and how learning about the Young Lords’ powerful story and being in the book circle helped him recenter and replenish. While we were learning about Puerto Rican and Mexican youth in ’60s Chicago, we were also healing and decolonizing the mind of the young student within us, who rarely saw themself or their authentic stories in school books. As told by Fernández, the Young Lords story opened a window to the often unforgiving historical context within which youth of color came of age in postwar Chicago: migration, deindustrialization, and the struggle to assert their humanity and place in the city in the face of white resentment, violence, and resistance. As we deepened our own political analysis through stories we had never heard before, we also experienced the power of bringing people together for political education. What started as lessons for my children during the pandemic transformed a group of teachers into students of the Young Lords and the broader history of which they were a part.

Gathering Others to Learn and Share

After the first book circle, many of us decided to plan a larger virtual national event about the Young Lords. We wanted to keep the momentum going, continue to read and learn about the Young Lords, and build together. We decided to focus our first event, held in October of 2020, on Cha Cha Jiménez’s story — his family’s migration from Puerto Rico to the United States and eventually to Chicago in the 1950s; the constant housing displacement imposed on his family by “urban renewal”; the racialized violence at the hands of white ethnic gangs that he and his friends endured as children — violence that prompted the formation of gangs amongst youth of color for protection and self-defense. Cha Cha’s radicalization was catalyzed during time spent in Puerto Rico and a stint in prison, where he read The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King’s Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?, which helped him develop a critical consciousness about the social issues that shaped him, his family, and his community.

Our event reflected the process we had created as a group: Fernández led a mini-lecture; we played an interview she conducted with Jiménez that focused on his radicalization. We used breakout groups to provide more intimate spaces for folks to process and share. And many of them shared so vulnerably and openly as they made connections to the story of the Chicago Young Lords.

One attendee from a suburb in Seattle said: “For so long I’ve been the only Puerto Rican in my community. . . . I would share my stories and often it would be a window for people . . . they see right through it and they don’t understand. For once, I feel like I’m reflected back. There are so many stories [here] that are mirrors. For once I felt a sense of belonging and community.”

Another attendee shared, “This is the first time I’ve been in community with others who have deeply reflected on the Young Lords and what they meant to them.”

One of our younger members read an excerpt from “Puerto Rican Obituary” by Pedro Pietri, poet laureate of the New York Young Lords. The poem tells the story of the Puerto Rican diaspora through five characters in what was a new, avant-garde literary style at the time, spoken word.

They worked

They were always on time

They were never late

They never spoke back

when they were insulted

They worked

They never took days off

that were not on the calendar

They never went on strike

without permission

They worked

ten days a week

and were only paid for five

They worked

They worked

They worked

and they died

They died broke

They died owing

They died never knowing

what the front entrance

of the first national city bank looks like

We ended on a high note with Chicago Black Boricua artist and DJ Sadie Woods, who played a house set during our virtual after-party. The work of organizing such a powerful event and seeing it to fruition sustained us as a group and inspired us to keep gathering with others.

Young people will tell you the truth, and we wanted to hear their reactions.

Summer Camp!

After our second virtual event, which focused on Fred Hampton’s leadership in the Chicago Black Panthers and his vision for the Rainbow Coalition, some of the educators in the group started thinking about a Young Lords curriculum for young people. To co-create and test this curriculum, we organized a summer youth camp. We recruited campers aged 12 to 18 through social media and a ton of outreach to educators, colleagues, youth groups, and parents and guardians. We ended up with 18 Black, Latinx, and Asian young people; eight identified as boys and 10 identified as girls. When asked why they applied for the camp, their responses included:

- I want to make a change.

- I want people to see us Puerto Ricans, our POV, & help the world be a better place.

- I feel like there are a lot of things in this world that need fixing. History tells us that young people lead the movements that create the most change. I want to learn about how I can make a contribution to my community.

As we read applicants’ responses, we saw the possibility for intergenerational connections and learning. Plus, as we all know, young people will tell you the truth, and we wanted to hear their reactions to the curriculum draft.

Fernández flew to Chicago from New York to lead lessons for the campers that took us from the origins of the Chicago Young Lords to the class-based solidarity of the Rainbow Coalition and even the origins of slavery. The campers heard testimonios from Omar López, former minister of information of the Chicago Young Lords, and David Stovall, professor in the Departments of Black Studies and Criminology, Law, and Justice at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Campers engaged in a Bomba dance intensive led by Ivelisse Diaz, directora de La Escuelita Bombera de Corazón, with guest artists Denise Solis and Marien Torres.

Fernández’s first lesson began with Cha Cha’s migration to Chicago as a child, which she contextualized as part of the mass migrations — from countryside to city — of historically racialized people in the United States during the post-World War II period. The migrations to the cities of Puerto Ricans from Puerto Rico, Black Americans from the South, Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Native Americans from the Southwest transformed these populations into a working class and set the stage for the rise of the civil rights and Black, Brown, and even Yellow power movements. After the campers learned more about the pull factors of Puerto Rican migration, they reflected on their own stories of migration. We asked them to write responses to the prompts “Why do people migrate? What is your story of migration? How did your family or your ancestors arrive in Chicago and why?”

Fernández acknowledged that they may not know their story of migration and that is an important truth to share as well. Campers wrote on their own for 15 minutes, and then paired up with partners and shared their stories. After each camper shared their story with their partner, we brought the whole group together and asked students to share the similarities and differences in their stories and in that of Cha Cha’s. Throughout the week, campers continued learning about the story of the Chicago Young Lords, alongside post-World War II and ’60s history.

As a summative project, the campers chose an issue that mattered to them and we supported their analysis with a root cause protocol. Campers researched their issue using a historical and economic lens. Protocol questions included “When did the problem start? How did the problem show up in the distant past? What does the economy have to do with the problem? How are people of different classes affected?”

After answering these questions, campers were asked to think about strategy. Guiding criteria included 1. Learn how people have responded in the past and how the system responded to people’s demands, and 2. Be clear about what you want, why you want it, and who you want it for.

On the last day, the campers presented their “platforms” to the group. Then political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal called and spoke to the students about the significance of his experience in the Black Panther Party. In the afternoon, we brought back Sadie Woods, who shared the story of her It Was a Rebellion mixtape and celebrated the students’ platform speeches with a custom DJ set.

Students reflected on their experience. “I got to know more of my worth,” one camper shared. “I got to know others and their point of view and how to listen to every single word a person has to say about their story because their story can be so big. . . . Listening to the Young Lords’ story and the Black Panthers’ story, it’s a lot and it’s so good.” Another student committed to taking their experience back to their school and sharing their learning with other students. Ultimately, this was the goal of the camp — to support the campers’ sense of agency and possibility within their lives and communities.

Connect as You Build

Every time we organized an event, we learned something new about the Young Lords and the ’60s freedom movement. But it was through the creation of the Young Lords curriculum that we engaged in the nuanced learning that happens when you make time for focused research. One of these moments happened when we asked permission to use Aurora Levins Morales’ poem “Child of the Americas,” which uses powerful language and imagery to beautifully capture the complexities of Puerto Rican identity. After asking the permissions agent to use the poem in our curriculum, I received an enthusiastic reply from Morales herself. I always thought she was part of the Nuyorican movement of poets in New York, and was shocked when she shared that she lived in Chicago in the 1960s and had heard Fred Hampton speak. Her father taught Puerto Rican history classes to the Chicago Young Lords. She connected me to her brother, social justice artist Ricardo Levins Morales. One of his pieces depicts a Young Lord gardening as part of their People’s Park project. In the midst of the forced displacement of Puerto Ricans from Lincoln Park, the Young Lords took over a plot of land in the neighborhood and created a communal space for young people. Through searches for images and conversations with museums and university curators, we were able to locate images of the People’s Park and other buried documentation of the Young Lords’ organizing.

Share Early, Share Often

As the research continued and the curriculum writing moved too slowly for my comfort level, a colega urged, “Don’t keep your stuff from others.” She could tell that I was feeling the pressure to create a polished, finished curriculum. (I still do!) But her words made me realize that, even in its unfinished state, we had something powerful to offer teachers.

In May 2022, a colleague offered to pilot the first unit of the curriculum, which focuses on the origin story of the Young Lords and culminates with students writing counter-narratives, much like the counter-narratives Jiménez and other Young Lords created in their own lives. The next fall, a small group of us organized a two-session workshop for Chicago teachers on the Chicago Young Lords. On the first day, teacher-participants engaged in an inquiry learning process. They explored primary sources, including photos of Young Lord demonstrations and events, articles from the Young Lords’ newspaper, and articles about the Young Lords in the mainstream press. Documents were organized by themes, in four centers: 1. Puerto Rican Migration; 2. Beginnings of the Young Lords’ & Cha Cha’s Radicalization; 3. The Young Lords’ Radicalization; and 4. Community Transformation.

After teacher-participants’ curiosities about the Chicago Young Lords were sparked, Omar López, Johanna Fernández, the teacher who piloted the first unit, and two of her students, who were also campers in our summer camp, shared their stories. The father of a member of our group, Edwin Cortés, who was a political prisoner in the United States for supporting Puerto Rican independence, also spoke. We played and discussed the documentary component of Bad Bunny’s music video Apagón, about the United States’ role in displacing Boricuas from our island. Even without a perfectly finished curriculum, teachers shared their excitement and commitment to bringing the Young Lords to their students.

Outside/Inside

From the beginning, our group has functioned outside traditional education spaces. This has provided flexibility and freedom to build and create at our own pace, process, and political perspective. But it has also been important to have allies in the system who support ethnic studies because there is so much power and possibility in a classroom.

For example, we originally tried to host the event at Lincoln Park High School because so many of the Young Lords attended the school and it’s vital for the students at the school to know this community history. When that didn’t work out, school leaders at Darwin Elementary and Moos Elementary, two community Chicago Public Schools, warmly hosted us. And through one of our connections, the Chicago Public Schools social sciences department distributed our event flier. There will always be challenges working with large systems, but many ethnic studies supporters work within these structures, and all students need to learn ethnic studies content and framing.

Coming Back Home to Ourselves

In her poem “Here,” Dominicana and Boricua poet Sandra María Esteves says:

I may never overcome

the theft of my isla heritage

dulce palmas de coco on Luquillo

sway in windy recesses I can only imagine

and remember how it was

but that reality now a dream

teaches me to see, and will

bring me back to me

Although I grew up in a large, loving Puerto Rican family in which we always spoke Spanish first, made pasteles, danced salsa in our living rooms, and enjoyed camping and fishing trips with three generations of relatives, our elders did not share stories of resistance with my cousins and me. There was a time when I felt frustrated about this, even angry. But when I read Cha Cha’s realization of his own parents’ circumstances as Puerto Rican migrants, it helped me understand why my parents and family were not able to share these stories. They were too busy surviving and adapting to life in Chicago, secretly mourning their beautiful land. In some cases, perhaps they had internalized the racism and colonial mentality that was inflicted on them. So, as I learned more about my history, in the practice of decolonizing my mind, I was healing my heart and feeling deep empathy for and connection with my elders and ancestors. This has been the most profound result of my relationship with ethnic studies.

But you don’t have to be a Boricua to understand the historical and present-day impact of colonialism and imperialism through the story of the Young Lords.

It’s not just about Puerto Ricans. It’s about Latinos, it’s about oppressed people, it’s about progressive people, it’s about Black Lives Matter today, it’s about everything that’s going on. It’s a connection. It’s a protracted struggle. It’s called unite the many to defeat the few — that’s how we’re gonna win.

These powerful words from Cha Cha (quoted in “Once a Street Gang, Then a Political Collective, the Young Lords Celebrate 50 Years with a Symposium at DePaul,” by Kerry Cardoza, Chicago Reader, Sept. 21, 2018) capture the vision so many young Chicagoans organized and sacrificed for in the ’60s, and continue to organize today. Ethnic studies is for all of us, and is about all of us, across the world, not just in Chicago or our country.

In the spirit of Robin D. G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, my freedom dream is that we nurture learning and growth in our teachers as much as we nurture growth in our students. Let’s create safe spaces that welcome educators with varied levels of political education knowledge. Spaces that allow us to release the shame and blame we carry and inflict, because we understand that we too were robbed of the truth. Let’s create spaces where we come together vulnerably, never feel alone in this work, and can count on community care when we need it the most. And let’s always remember, together, how our individual knowings are catalysts for young people, so they too can come back to and hold on to themselves.