Rethinking Schools published Linda Christensen’s Reading, Writing, and Rising Up in 2000. The original book, Linda says, was based on her first 20 years in the classroom at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon. Since then, Linda’s work has been recognized as an essential resource for integrating social justice into language arts classrooms. She followed the first edition of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up with Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-imagining the Language Arts Classroom and Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice, which built on her work of engaging students with writing by integrating their lives into the classroom.

The second edition of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up captures her imperative of bringing students’ lives into the classroom not just to build literacy skills, but to help students uncover the roots of inequality and meet real and imagined people and movements who have worked for change.

It’s been almost 20 years since the original Reading, Writing, and Rising Up arrived. Linda has spent several years — in between her work as director of the Oregon Writing Project and working with teachers locally and throughout the country — rewriting, revising, and reteaching the lessons in Reading, Writing, and Rising Up.

The new volume is fully revised and features new sections, updated lesson plans, and exemplary student work. The book is a gift to a new generation of students and teachers. We sat down with Linda to talk about what readers can expect.

Rethinking Schools: What was the process of revising and putting together the second edition of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up?

Linda Christensen: I had a whole new body of material that I had been working on since the original Reading, Writing, and Rising Up came out, and a few people thought that some of the articles in Reading, Writing, and Rising Up (particularly the cartoon unit “Unlearning the Myths that Bind Us”) were dated.

That led me to think about whether I wanted to write a new book or if I wanted to update Reading, Writing, and Rising Up. I thought about it a lot, and there were so many teaching pieces in Reading, Writing, and Rising Up that I still used and that still resonated with other educators, so I decided to do a full revision of the book rather than creating a new book.

I talked to a number of teachers and professors who use the book and asked them what pieces they thought remained current and what pieces they thought needed to be revised. Then I went back through and looked at each of the articles. My production editor, Kjerstin Johnson, also examined the book for places that were dated. Then I retaught almost every lesson to see how they worked today, whether they were still relevant, and what needed to be changed.

You said you retaught many of the pieces. What role did the classroom play in the second edition?

The classroom is my source of inspiration. Out of the classroom I can create curriculum, but I need to observe students, listen to their class talk, and read their pieces to determine whether the lessons land or fall with students. I needed to see how lessons resonated with students today versus students 20 years ago. I keep returning to the classroom because it’s where I find my joy. I can’t think about teaching in isolation, away from classrooms.

I have been fortunate to have a cadre of teachers at Jefferson High School who have welcomed me into their classrooms to work. For two years I co-taught a junior English class with the amazing teacher Dianne Leahy. A lot of the new and revised material came out of going back through and spending two years in the classroom reworking, revising, and creating new material with Dianne. Another swath of revision came from going back into classrooms of individual teachers, like Andy Kulak, Ellie McIvor-Baker, Nyki Tews, Amy Wright, and Dan Coffey, and working with them on new pieces that I created and workshopped in their classrooms.

The newly revised “Unlearning the Myths that Bind Us” was recently published in Rethinking Schools magazine. How was that piece updated?

I originally taught — and still teach — the cartoon unit as a way of getting students to understand critical lenses we bring to literature and life: the way we look at men and women in society, the way we look at class issues, the way we look at race issues, the way we look at language issues. Those are critical lenses that I want students to develop so that they stop reading just to find the story line, or who the characters are, or how the characters change, and instead read as a way to investigate society. Because cartoons are short and easily accessible, they provide a great place for students to see how these issues have changed and how they haven’t changed in a short amount of time.

In terms of revision, I was concerned because I hadn’t been watching cartoons since I stopped teaching the unit. A new generation of cartoons, movies, and animation had come out since I wrote the original piece, so I needed to catch up on all of those and rewatch the originals to see what had changed. And honestly, very has little has changed. Sexism, racism, and classism are alive and influencing children’s understanding in similar ways today.

The one thing that I think was especially helpful was working with Jayme Causey, who was a first-year teacher at Jefferson High School. We redesigned the cartoon unit for the freshman year at Jefferson High School. The lens that Jayme brought was the idea of hyper masculinity. I viewed cartoons through a feminist lens, but I wasn’t seeing what these kinds of images were doing to boys. He helped me see that. So that was one big change.

Were there big differences between the cartoons you looked at now versus those in the original lesson?

It was really the kids who saw it. We brought in Brave, a new cartoon about a young woman who refuses to be given over as the possession of a man. She’s a Celtic princess and saves the land through her excellent archery. Those were things that changed — there was more of a feminist message. The thing that remained the same was that she continued be the hourglass figure, the beauty; that the poor people continued to be buffoons; that we always look to the rich and powerful for inspiration and saving.

The first book was written about 20 years ago; a lot has taken place even in the past five years — the Black Lives Matter movement, the Trump administration, among many others. How were more recent social issues integrated into the book?

As teachers, we have two kinds of parallel drives in our work. One is to help our students understand contemporary, breaking news like DACA or Charlottesville. There’s an immediacy of issues that we need to address. But there’s also a big curriculum and skill set that we still need kids to learn. And so the question is, how do we do both at the same time? How do we make sure that we are helping students understand contemporary society but also helping them understand the critical and historical roots of where these problems originated?

The “Danger of a Single Story: Writing Essays About Our Lives” curriculum came out after the murder of Trayvon Martin and the subsequent murdering of Black people. I created this lesson as a way to respond to the racism and police brutality that Black people encounter. But through the lesson, I also taught students how to develop an essay by using vignettes from their own lives, following Brent Staples’ model essay. Every lesson must feed multiple objectives.

The lesson “Burned Out of Homes and History: Uncovering the Silenced Voices of the Tulsa Race Riot” was built to help students understand racism historically — Trayvon Martin was not the first; Ferguson was not the first; there’s a historic lineage of violent racism in the United States. The 1921 Tulsa “Race Riot” is a textbook example of racism and the KKK at work, like we saw in Charlottesville. Again, the unit taught students how to read history critically, how to write historical fiction, and how to understand contemporary society by looking to the past.

I created “Rethinking Research: Reading and Writing About the Roots of Gentrification” as a way to understand what was happening to their neighborhood through gentrification. But one can’t understand gentrification without understanding the historical, racist roots that paved the way, from redlining to “urban renewal.” But it’s not like students learned about this instead of working on their skills; they flexed their literacy muscles by reading articles from multiple sources, taking historical walking tours led by a former Jefferson student, Lakeitha Elliot, and writing poetry, narratives, essays, and historical fiction using primary and secondary sources from the unit.

Two areas that were greatly expanded were the section on literature and the section on responding to student work.

“Reading for Justice, Reading for Change,” the new literature section, came about as a response to questions that arise when I am working with teachers like, “How do I make sure students read the book? If I don’t give quizzes, they won’t read.” The section also came from my evolving understanding about teaching. Instead of reading as a “gotcha” — i.e. “Did you read the assigned pages?” — I want to have engaged conversations about literature and society. I need to teach literature to help illuminate the problems in the society that they live in and help them imagine the society that they want to live in. Novels help us both envision and change our lives. Novels unravel the complex interplay between our race, gender, sexual orientation, class while examining the way society views us, marginalizes us, erases us.

So in the new literature section, I was thinking about how students interact with the text that brings their lives into the text more and helps them understand parallels between their lives and the lives of the people that we’re reading about. I also wanted to demonstrate the more active strategies I use when teaching literature. Instead of me controlling the discussion about the text, the students control the discussion and find parallels in their lives and society — from writing poetry about characters to creating life-size character silhouettes to building theme and evidence walls as we read.

Similarly, there is a movement that tries to make it “easy” for teachers to grade student writing by having rubrics or four-, six-, or eight-trait scales that provide quick ways to “respond” to students’ work. The chapter “Responding to Student Writing” came out of my reaction to that movement. For students to develop their writing skills, it is critical that they learn to revise their work. For that to happen, students need to own their work and have conversations about their writing with their peers and their teachers. They need to notice the kinds of changes they make and how that improves their writing — from adding dialogue to a narrative to adding commentary to an essay or getting rid of passive language. And yes it is time consuming, and yes it is messy, but it is really the only way students grow. Much of this work came out of lessons I teach in high school classrooms, but also out of the work I do with teachers in the Oregon Writing Project summer institutes.

I used to feel that unless I marked up every inch of an essay with a red pen and pointed out every error that I was not doing my job. I just want to say that’s not our job; our job is to make students better thinkers. It’s not that I have to get this piece of writing right, it’s that I have to teach them how to revise this piece and write the next piece better. I have to teach them an ongoing skill rather than this momentary “where to put a comma.” That overcorrection stands in the way of students getting better at thinking — which is what writing is about — and instead focuses on correction.

Where do you see Reading, Writing, and Rising Up in the landscape of your other work?

I see Teaching for Joy and Justice as the nuts and bolts of how to teach a language arts classroom: How do you teach literature, how do you teach essay writing, how do you teach narrative writing? Rhythm and Resistance focuses on how and why to teach poetry.

Reading, Writing, and Rising Up is about interrogating society through literature. It’s about awakening consciousness, awakening students to the injustice in the world, awakening them to their magic — to their strength and wisdom, and helping them find that. It is about what we can do with our lives and how we can make changes in them. It’s about how we as teachers can work with students to make that happen, to challenge us to say “This is our work” — that our work is not just putting a red pen on paper or making sure that students have read a very traditional canon, it’s about creating their desire not just to read but, as Paulo Freire says, to read the word and the world.

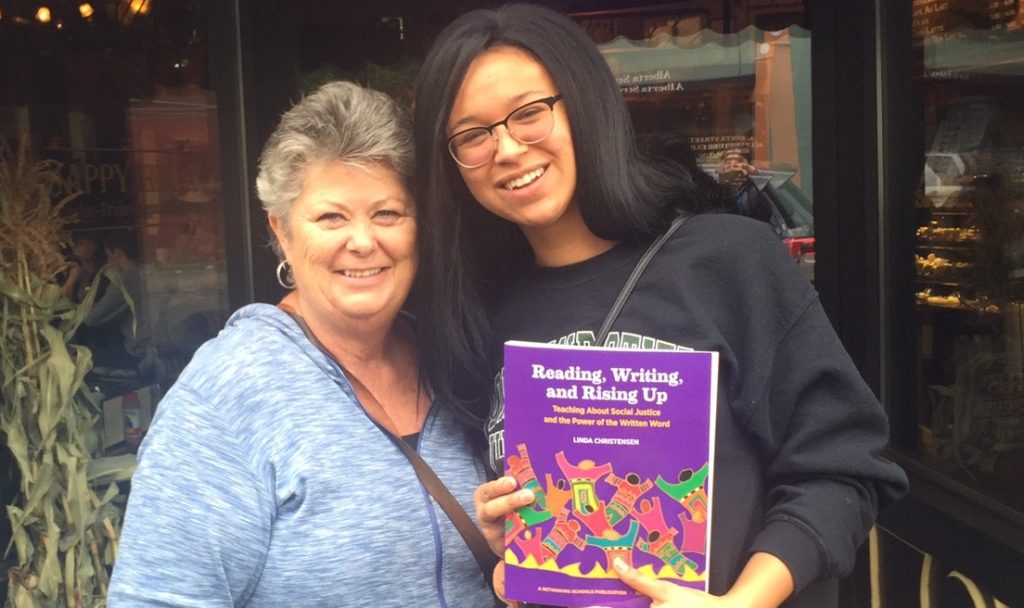

Featured photo (top): Linda Christensen and Desiree’ DuBoise, a former student whose work appears in the second edition of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up.

Linda Christensen is the director of the Oregon Writing Project at Lewis & Clark College in Portland. Christensen taught high school language arts for most of four decades and worked as the Language Arts Curriculum Specialist in Portland Public Schools. She has worked as an editor and writer for Rethinking Schools for 30 years.

In addition to Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word, Christensen is the author of Teaching for Joy and Justice: Re-Imagining the Language Arts Classroom. She also co-edited Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice, Rethinking School Reform: Views from the Classroom, Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 1, The New Teacher Book: Finding Purpose, Balance, and Hope During Your First Years in the Classroom, and Rethinking Elementary Education.

Christensen is a recipient of the Fred Hechinger Award for use of research in teaching and writing from the National Writing Project, the U.S. West Outstanding Teacher of the Western United States, the Paul and Kate Farmer Writing Award from the National Council of Teachers of English, the Oregon Education Association’s award for Professional Development, the Horace Mann Community Upstander award from Antioch College, among many other awards. The Linda Christensen Social Justice award, named in her honor, is given annually at Kalamazoo College in Michigan.