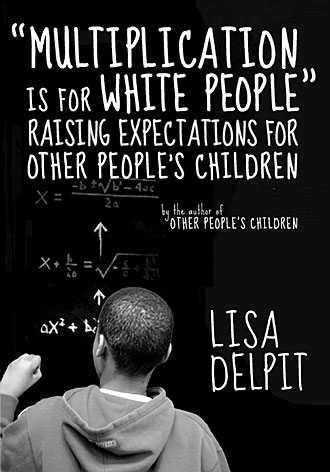

“Multiplication Is for White People”

An interview with Lisa Delpit

In the introduction to her new book, “Multiplication Is for White People”: Raising Expectations for Other People’s Children, Lisa Delpit describes her response when Diane Ravitch asked her why she hasn’t spoken out against the devastation of public schools in her home state of Louisiana and the efforts to make New Orleans the national model. She explained to Ravitch that she has been concentrating her efforts where she feels she can make a difference: working with teachers and children in an African American school. She says her “sense of futility in the battle for rational education policy for African American children had gone on for so long . . . that I needed to give my ‘anger muscles’ a rest.”

But that interchange made her realize that she is still angry, and that anger fuels and defines Multiplication Is for White People. “I am angry,” she begins, “that public schools, once a beacon of democracy, have been overrun by the antidemocratic forces of extreme wealth.” As she continues to enumerate the sources of her anger, the introduction comprises a focused and comprehensive indictment of the neoliberal attack on public education.

Two themes drive Multiplication Is for White People: Delpit infuses the interplay between her role as a scholar/activist and as the mother of a child with a unique learning style. And she organizes her text around 10 factors she believes “foster excellence in urban classrooms.”

Because children who don’t fit the white middle-class norms, especially those with real and/or perceived learning differences, are among the most marginalized by the scourges of corporate education reform, I chose to start my interview with Delpit there.

Jody Sokolower for Rethinking Schools: You say in your new book that middle-class children come to school with different—although not more important—skills from children from low-income families. What do you mean? And is this a class difference or a cultural difference?

Lisa Delpit: It is difficult to disaggregate class and culture. Children who have to take on more responsibility in real life will know and be able to do those types of things earlier. The specific responsibilities they take on are cultural—that would be different for Alaskan children as opposed to African American children or Appalachian children. We in middle-class families tend to keep our children young longer, to infantilize them.

This difference has great significance when we think about schools. If we are going to ensure that all children learn to read, I believe we have to turn our notion of “basic skills” on its head. What we call basic literacy skills are typically the linguistic conventions of middle-class society—for example, punctuation, grammar, specialized subject vocabulary, and five-paragraph essays. All children need to know these things. Some learn them from being read to at home. What we call basic skills are only “basic” because they are one aspect of the cultural capital of the middle class.

What we call advanced or higher-order skills—analyzing new information, evaluating the relative merits of concepts and other problem-solving skills—are those that middle-class children learn later in life. But many children from low-income families learn them much earlier because their parents place a high value on independence and real-life problem-solving skills.

So children come to us having learned different things in their four-to-five years at home, prior to formal schooling. For those who come to us knowing how to count to 100 and to read, we need to teach them problem-solving and how to tie their shoes. And for those who already know how to clean up spilled paint, tie their shoes, prepare meals, and comfort a crying sibling, we need to make sure that we teach them the school knowledge that they haven’t learned at home.

JS: How does this relate to children who are seen as having learning disabilities or special needs?

LD: The biggest issue for all children is not that we don’t see what they don’t know, but we don’t see what they do know, what they do come to school with. They learned something in those years since they entered the world.

JS: You quote a young woman who struggled with learning in school who wonders why learning differences are classified as negative attributes—”Can we not focus on strengths and positive attributes?” she asks. How could it be different?

LD: I am not a special education teacher, nor am I a specialist in special education research, so I don’t want to position myself as an expert. But I do sometimes ask teachers to identify the students who are considered the most problematic in their class for whatever reason, be it behavior or be it in academic areas, and to write down 10 ways in which they are exhibiting difficulty or challenges. Then I ask the teachers to look at those challenges and see if they can be redefined as strengths, or if they can find other strengths in those children.

One teacher said, “I’m looking at this child who is disruptive and all the other children do what he or she does.” She was able to translate that into “This is a leader. I need to give this child leadership roles so that she can assist me rather than detract from what I’m doing.” Another child was always tattling: “So and so did such and such.” So she reinterpreted that as a way of looking out for others—getting into a fuss with somebody because they did something to another child. So then she was able to translate that into nurturing behavior and to give the child roles that would allow her to nurture without creating a problem.

No matter what the child brings, be they special needs or learning disabilities or whatever label we want to put on them, instead of looking at the label and the problem that the label might represent, we can look at the person and see what strengths are there and what we can build on.

JS: Why do you think there are so many African American children in special ed programs?

LD: I think there are a multitude of answers. The larger society has a view of African American people as being less intellectually capable. It’s not something that anybody designed or set out to do, but it’s almost in the air that we breathe. And as a result of that, when African American children do poorly, the first explanation is that there’s something inherent in them that’s keeping them from performing well. In fact, as Beth Harry and Janette Klingner say in their book Why Are So Many Minority Children in Special Education? Understanding Race and Disability in Schools, much of the time the reason is external to the child—for example, poor instruction, or maybe something happening in the family or community that caused trauma. But the official explanation tends to be that there’s something wrong with the child.

Another piece is that the behavior of many boys, particularly African American boys, is seen as pathological. Some white female teachers from middle-class families (who are, of course, most of our teachers) are not accustomed to seeing this behavior and so they tend to think of it as something that is abnormal. There may be a higher tolerance for movement within some cultures that teachers again may not be accustomed to.

Another thing we run into a lot is young African American students who have learned what some people refer to as street sense, but their language might seem more mature in many ways. Teachers who are not familiar with the culture of the children actually get fearful and their fear pushes them to direct more African American kids to special education.

JS: With all the pressure on “seat time” and standardized tests, schools have less tolerance for movement than they used to.

LD: Yes, the norms of regular classrooms are often so restrictive that any deviation suggests a pathology. So you get more African American children whose cultural norms may be a little different being directed into special education. Often teachers just don’t know how to best reach these kids, how to connect to what they know, how to connect to what their interests are, and that plays a part in it, too. So there are numerous reasons, but I think the largest one is the underlying belief system—and not just among white people, among all Americans, often including black people—that African American students are less capable.

JS: Many of the factors you mention aren’t about learning, they are about behavior. So part of what you’re saying is that kids are being treated as having learning disabilities when it is actually a question of behavior.

LD: Well, there is a category called behavior disorders. It changes from state to state exactly what the wording is, but there’s actually a category for behavior issues. And that’s the one that many black boys particularly are referred into.

Even among African American children who are labeled as having learning disabilities, they face the psychological trauma of not having those learning problems specifically defined. When you have a specific learning difference, you can understand that you have strengths and weaknesses as a learner. You can receive help to overcome that specific issue. But many African American children are labeled “slow learners” or “educable mentally retarded/behavior disordered.” It’s very difficult as a student to see what your strengths are in that context, and many times they don’t get the specific help that they might need.

JS: Do you think there is enough emphasis on critical thinking and social justice education in special ed classes?

LD: Critical thinking and social justice issues are factors that everyone in the United States needs to tackle. I also think that the more disconnected the content we teach—the more teachers try to teach skills out of context—the less likely students are to make sense of it. So we have to talk about the big picture, then use aspects of that discussion to look at specific skills. When we isolate or decontextualize skills or facts, they are just meaningless little pieces that don’t make any sense.

In my book, I talk about the work of Petra Munro Hendry, who did oral history with a group of low-performing black kids at a high school in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The students researched the history of their school, which turned out to be one of the first public high schools for black students in the entire southern region of the country. In the context of doing that, they interviewed people, they recorded interviews. If you think about what you have to do when you take an interview and transcribe it, you have to learn spelling, you have to learn punctuation, you have to learn capitalization, you have to learn how to create a real sentence out of what somebody said who may not have spoken distinctly and clearly, or who has had some “um’s” and “uh’s.” In other words, you have to learn what is taught in a remedial class, but it’s put in the context of something much bigger and much more important. The students said to themselves: “We are researchers. We are people who are doing the kind of work that one might find college students doing.” Not: “We are remedial learners.”

And that is the way that we need to go to teach the small pieces like grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and spelling, rather than just keep those in isolation.

JS: How important is it to have a diversity of teachers in a school? How important is it for students to have a teacher who looks like them, who comes from their culture?

LD: I think what we need is people who represent the culture of the kids in the school, not necessarily in every classroom, because I think teachers of other cultures also have something to offer. However, I think that the piece that is often missing in our schools is the opportunity for professional learning communities where teachers can share what they know and collectively resolve issues relating to culture as well as other factors. If we can do that and ensure that the people who are most familiar with the culture of the children have the opportunity and the responsibility to share some of that knowledge with other teachers, then we will be doing OK. If the culture of the school is set up so that sharing is important and collaborating is important, the children will be the beneficiaries.

Jennifer Obidah and Karen Manheim Teel wrote a book, Because of the Kids: Facing Racial and Cultural Differences in Schools, about a white teacher who was having some difficulty in class and approached an African American teacher for help. The African American teacher spent some time in the classroom, they worked collaboratively and had some arguments about different kinds of things. At the end they were able to figure out what each could learn from the other and the culture piece came to the forefront. They were able to resolve the issues and create a better situation for the children. I don’t want to make the claim that all black teachers are better or that every black teacher is good for every black child because, as I mentioned before, many of us have also internalized negative notions about black children. We really have to look at the specific teacher and what the teacher’s beliefs are and how the teacher sees the culture of the children, regardless of the teacher’s ethnicity. But black kids need black teachers’ presence in the school, and white teachers need black teachers’ presence in the school.

JS: You talk about the need to neutralize, educate, or get rid of bad teachers. Can we do that without standardized tests?

LD: There are a lot of pieces to that question. We do need to neutralize, educate, or get rid of bad teachers—that is true. But I think we need to take another look at assessment. If we can create professional learning communities where everyone is responsible to everyone else and we have a joint responsibility for these children in the school, then we can create a situation where teachers can do a lot of peer assessment of other teachers.

Many teachers are not using a quarter of what they know because the school environment is so foul. And we know that the culture of the school very much affects the teaching that goes on in classrooms. So my question becomes not so much whether the teachers at a specific school are good or bad but what is it in this setting that’s not allowing them to teach to their full potential. And many times it is the question of trust.

Charles Payne has a great book, So Much Reform, So Little Change: The Persistence of Failure in Urban Schools. One of the things that he brings out is that the level of disorganization and mistrust in a school affects how well a teacher teaches. I don’t think we can just look at the individual teaching level. We have to look at the school: What about the school is not allowing teachers to teach to their potential? So the problem may be the environment, or it may be some skills that teachers are lacking, or it may be that it’s time for some teachers to look into other areas of work.

One time, I went to visit a teacher’s classroom for the first time. He didn’t know who I was or where I was coming from. He proceeded—in front of the children—to tell me how terrible these students were. He told me that he had want.ed to be a lawyer but he fell into teaching, and now he thought these kids were not worth the effort. I was in shock. Finally I said to him, “Well, I think it is time for you to pursue your dreams. You need to go to law school.”

So sometimes it is important to help folks find where their talents will best be used so as not to destroy children. But most of the current notions of accountability are wrongheaded and will never improve what’s going on with teachers and what happens in classrooms.